Biodiv Sci ›› 2025, Vol. 33 ›› Issue (6): 24416. DOI: 10.17520/biods.2024416 cstr: 32101.14.biods.2024416

• Original Papers: Plant Diversity • Previous Articles Next Articles

Received:2024-09-18

Accepted:2025-03-11

Online:2025-06-20

Published:2025-07-28

Contact:

Zimin Hu

Supported by:Tongyun Zhang, Zimin Hu. The brown macroalga Fucus distichus revisited: Phylogeographic insights into a marine glacial refugium in the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, Canada[J]. Biodiv Sci, 2025, 33(6): 24416.

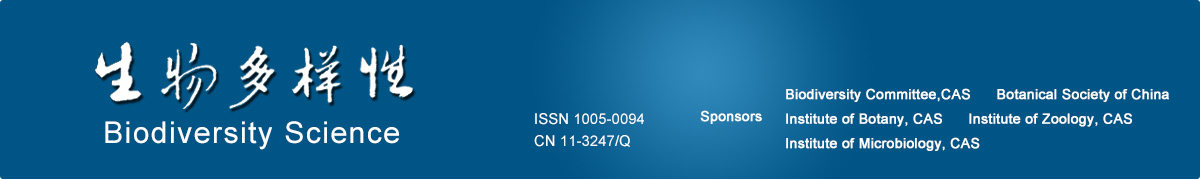

Fig. 1 The brief description of the brown alga Fucus distichus. (a) The morphology and habitat of F. distichus (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada); (b) The general dispersal history of F. distichus in the Pan-Arctic. The purple and green arrows indicate two separate trans-Arctic migration events of the ancestral F. distichus in the North Pacific into the North Atlantic. The purple and green circles represent two marine glacial refugia during the last glacial maximum on the northeast (northern Norway) and northwest (Newfoundland, Canada) Atlantic, where the survived ancestral populations expanded c. 12 ka to consequently form present-day distribution patterns. Ma, Million years ago; ka, Thousand years ago. (c) Sampling locations of F. distichus from the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, Canada.

| 采样地点 Sampling localities | 23S mtDNA基因间区 23S mtDNA intergenic spacer (IGS) | 细胞色素c氧化酶亚基 Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COX1) | 数据来源 Data source | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | h | π | hi | n | h | π | hi | ||

| 加拿大纽芬兰大浅滩 Grand banks, Newfoundland, Canada (GB1) | 27 | 0.5014 | 0.0046 | Hap1 (i1)-Hap3 | 27 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | Hap-1 (c1) | 本研究 This study |

| 加拿大纽芬兰大浅滩 Grand banks, Newfoundland, Canada (GB2) | 6 | 0.7333 | 0.0054 | Hap1 (i1), Hap2, Hap5 | 10 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | Hap-1 (c1) | 本研究 This study |

| 加拿大纽芬兰大浅滩 Grand banks, Newfoundland, Canada (GB3) | 10 | 0.6889 | 0.0078 | Hap1 (i1)-Hap3 | 6 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | Hap-1 (c1) | 本研究 This study |

| 加拿大纽芬兰大浅滩 Grand banks, Newfoundland, Canada (GB5) | 29 | 0.6897 | 0.0088 | Hap1 (i1)-Hap4, Hap6-Hap10 | 24 | 0.3080 | 0.0036 | Hap-1 (c1) -Hap-4 | 本研究 This study |

| 加拿大纽芬兰拱门 Arches, Newfoundland, Canada | 27 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | i1 | 12 | 0.3273 | 0.0008 | c1, c2 | Coyer et al, |

| 加拿大纽芬兰诺斯特德 Norstead, Newfoundland, Canada | 24 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | i1 | 12 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | c1 | Coyer et al, |

| 美国阿拉斯加阿图岛 Attu Island, Alaska, USA | 26 | 0.3624 | 0.0046 | i4, i5 | 12 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | c1 | Coyer et al, |

| 美国阿拉斯加威廉王子湾 Prince Williams Sound, Alaska, USA | 26 | 0.5200 | 0.0138 | i4, i5, i7 | 12 | 0.1667 | 0.0004 | c1, c2 | Coyer et al, |

| 美国缅因阿普尔多尔岛 Appledore Island, Maine, USA | 24 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | i1 | 12 | 0.5303 | 0.0013 | c1, c3 | Coyer et al, |

| 冰岛伊萨菲厄泽 Isafjörður, Iceland | 32 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | i1 | 12 | 0.5303 | 0.0013 | c1, c2 | Coyer et al, |

| 冰岛格林达维克 Grindavik, Iceland | 28 | 0.3042 | 0.0017 | i1, i2 | 12 | 0.1667 | 0.0004 | c1, c2 | Coyer et al, |

| 冰岛布雷兹达斯维克 Breiðalsvik, Iceland | 30 | 0.0667 | 0.0004 | i1, i3 | 12 | 0.5000 | 0.0013 | c1, c2 | Coyer et al, |

| 丹麦法罗群岛斯特罗莫岛 Streymoy, Faroe Islands, Danmark | 16 | 0.2333 | 0.0013 | i1, i2 | 12 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | c1 | Coyer et al, |

| 挪威哈默菲斯特 Hammerfest, Norway | 30 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | i1 | 12 | 0.5303 | 0.0013 | c1, c2, c3 | Coyer et al, |

Table 1 Genetic diversity indices of the Fucus distichus populations sampled from Grand Banks of Newfoundland (values highlighted in bold) compared with the populations with the highest genetic diversity published by Coyer et al (2011) (background colored by light grey)

| 采样地点 Sampling localities | 23S mtDNA基因间区 23S mtDNA intergenic spacer (IGS) | 细胞色素c氧化酶亚基 Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COX1) | 数据来源 Data source | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | h | π | hi | n | h | π | hi | ||

| 加拿大纽芬兰大浅滩 Grand banks, Newfoundland, Canada (GB1) | 27 | 0.5014 | 0.0046 | Hap1 (i1)-Hap3 | 27 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | Hap-1 (c1) | 本研究 This study |

| 加拿大纽芬兰大浅滩 Grand banks, Newfoundland, Canada (GB2) | 6 | 0.7333 | 0.0054 | Hap1 (i1), Hap2, Hap5 | 10 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | Hap-1 (c1) | 本研究 This study |

| 加拿大纽芬兰大浅滩 Grand banks, Newfoundland, Canada (GB3) | 10 | 0.6889 | 0.0078 | Hap1 (i1)-Hap3 | 6 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | Hap-1 (c1) | 本研究 This study |

| 加拿大纽芬兰大浅滩 Grand banks, Newfoundland, Canada (GB5) | 29 | 0.6897 | 0.0088 | Hap1 (i1)-Hap4, Hap6-Hap10 | 24 | 0.3080 | 0.0036 | Hap-1 (c1) -Hap-4 | 本研究 This study |

| 加拿大纽芬兰拱门 Arches, Newfoundland, Canada | 27 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | i1 | 12 | 0.3273 | 0.0008 | c1, c2 | Coyer et al, |

| 加拿大纽芬兰诺斯特德 Norstead, Newfoundland, Canada | 24 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | i1 | 12 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | c1 | Coyer et al, |

| 美国阿拉斯加阿图岛 Attu Island, Alaska, USA | 26 | 0.3624 | 0.0046 | i4, i5 | 12 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | c1 | Coyer et al, |

| 美国阿拉斯加威廉王子湾 Prince Williams Sound, Alaska, USA | 26 | 0.5200 | 0.0138 | i4, i5, i7 | 12 | 0.1667 | 0.0004 | c1, c2 | Coyer et al, |

| 美国缅因阿普尔多尔岛 Appledore Island, Maine, USA | 24 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | i1 | 12 | 0.5303 | 0.0013 | c1, c3 | Coyer et al, |

| 冰岛伊萨菲厄泽 Isafjörður, Iceland | 32 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | i1 | 12 | 0.5303 | 0.0013 | c1, c2 | Coyer et al, |

| 冰岛格林达维克 Grindavik, Iceland | 28 | 0.3042 | 0.0017 | i1, i2 | 12 | 0.1667 | 0.0004 | c1, c2 | Coyer et al, |

| 冰岛布雷兹达斯维克 Breiðalsvik, Iceland | 30 | 0.0667 | 0.0004 | i1, i3 | 12 | 0.5000 | 0.0013 | c1, c2 | Coyer et al, |

| 丹麦法罗群岛斯特罗莫岛 Streymoy, Faroe Islands, Danmark | 16 | 0.2333 | 0.0013 | i1, i2 | 12 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | c1 | Coyer et al, |

| 挪威哈默菲斯特 Hammerfest, Norway | 30 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | i1 | 12 | 0.5303 | 0.0013 | c1, c2, c3 | Coyer et al, |

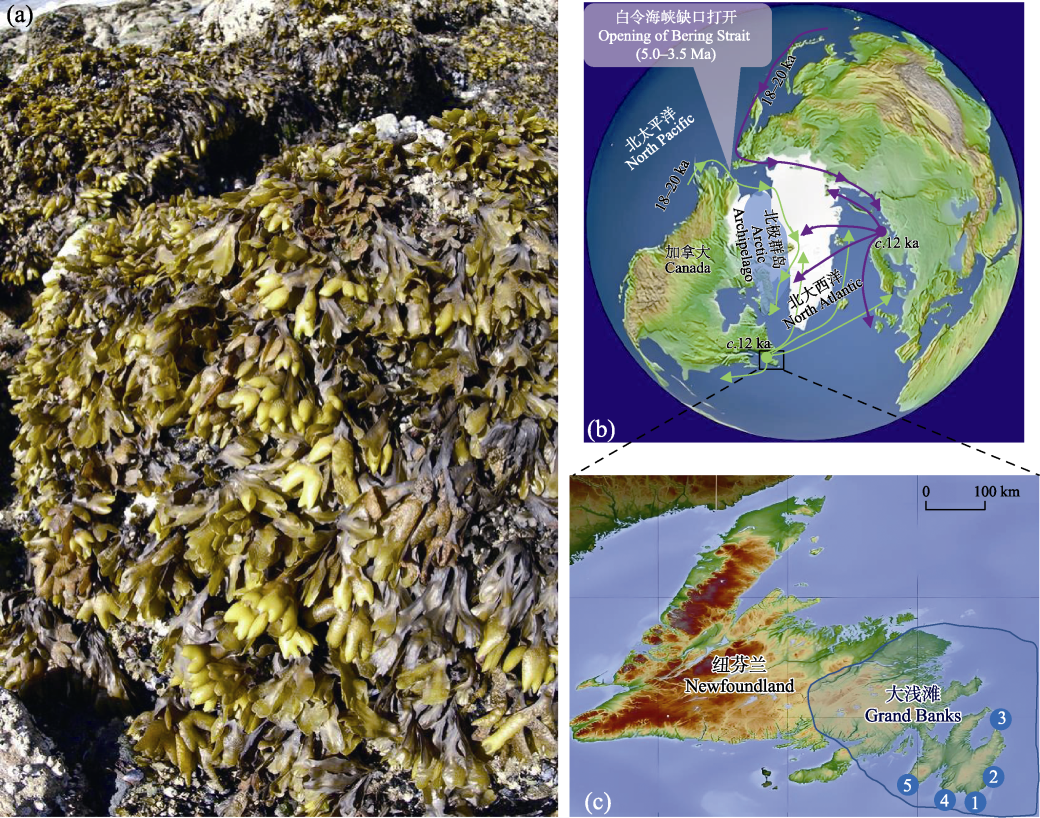

Fig. 2 The constructed haplotype network based on mtDNA COX1 (a) and 23S mtDNA IGS datasets (b). c1-c3 and i1-i7 are COX1 and IGS haplotypes reported by Coyer et al (2011), respectively, of which c1 and i1 are identical to Hap-1 and Hap1, respectively identified in this study. The black boxes (e.g. mv) represent the lost or missed haplotypes.

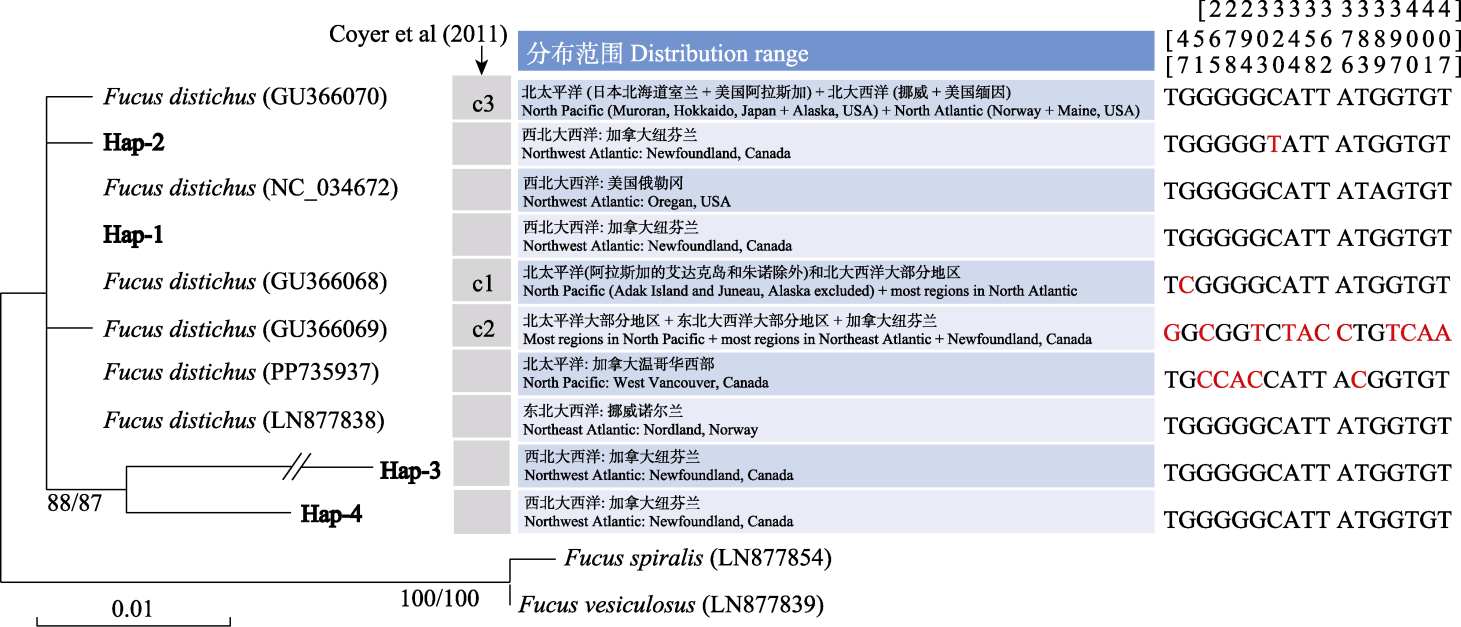

Fig. 3 Neighbour joining phylogenetic tree constructed using mtDNA COX1 haplotypes. Hap-1-Hap-4 in bold font are haplotypes identified from the Grand Banks of Newfoundland in this study. The characters in parentheses are GenBank accession numbers for each sequence, and the numbers on both sides of the slash are bootstrap values of neighbour joining and maximum likelihood algorithm (1,000 replicates). The arrow indicates the COX1 haplotypes reported by Coyer et al (2011). The nucleotide variations of each COX1 haplotype at different numbering sites (i.e. the numbers above the aligned nucleotides) are highlighted in red color.

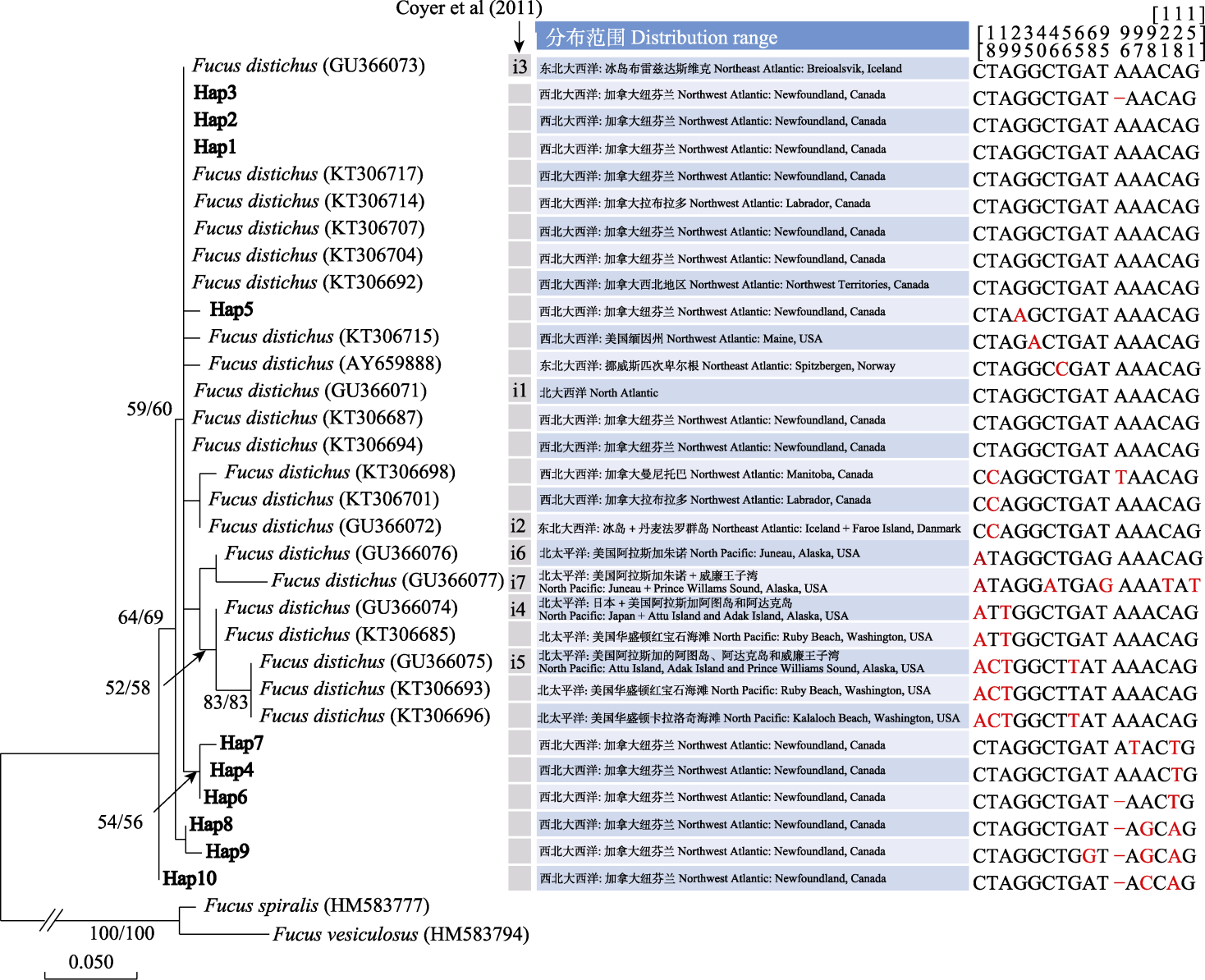

Fig. 4 Neighbour joining phylogenetic tree constructed using 23S mtDNA IGS haplotypes. Hap1-Hap10 in bold font are haplotypes identified from the Grand Banks of Newfoundland in this study. The characters in parentheses are GenBank accession numbers for each sequence, and the numbers on both sides of the slash are bootstrap values of neighbour joining and maximum likelihood algorithm (1,000 replicates). The arrow indicates the IGS haplotypes reported by Coyer et al (2011). The nucleotide variations of each IGS haplotype at different numbering sites (i.e. the numbers above the aligned nucleotides) are highlighted in red color. “-” in aligned sequences indicates missed nucleotide.

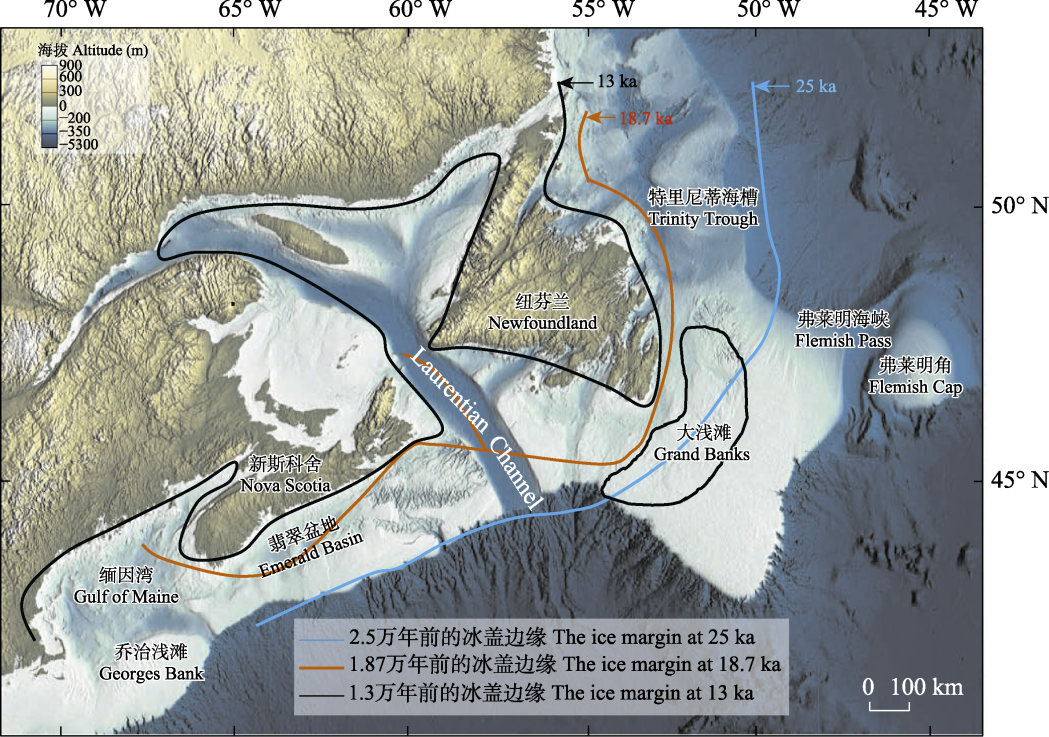

Fig. 5 The geographic location of the Flemish Cap relative to the Grand Banks, and the ice margin around Newfoundland at 25 ka (blue line), 18.7 ka (brown line), and 13 ka (black line). Modified from Shaw (2006) and Fan et al (2024). ka, Thousands years ago.

| [1] | Adey WH, Hayek LAC (2011) Elucidating marine biogeography with macrophytes: Quantitative analysis of the North Atlantic supports the thermogeographic model and demonstrates a distinct subarctic region in the northwestern Atlantic. Northeast Naturalist, 18, 1-125. |

| [2] | Adey WH, Lindstrom S, Hommersand M, Muller K (2008) The biogeographic origin of Arctic endemic sea weeds: A thermogeographic view. Journal of Phycology, 44, 1384-1394. |

| [3] | Allakhverdiev SI, Kreslavski VD, Klimov VV, Los DA, Carpentier R, Mohanty P (2008) Heat stress: An overview of molecular responses in photosynthesis. Photosynthetic Research, 98, 541-550. |

| [4] | Assis J, Araujo MB, Serrao EA (2018) Projected climate changes threaten ancient refugia of kelp forests in the North Atlantic. Global Change Biology, 24, e55-e66. |

| [5] |

Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Rohl A (1999) Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 16, 37-48.

DOI PMID |

| [6] | Berndt ML, Callow JA, Brawley S (2002) Gamete concentrations and timing and success of fertilization in a rocky shore seaweed. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 226, 273-285. |

| [7] | Bird NL, McLachlan J (1976) Control of formation of receptacles in Fucus distichus L. subsp. distichus (Phaeophyceae, Fucales). Phycologia, 15, 79-84. |

| [8] | Brawley S, Coyer JA, Blakeslee AMH, Hoarau G, Johnson LE, Byers JE, Stam WT, Olsen JL (2009) Historical invasions of the intertidal zone of Atlantic North America associated with distinctive patterns of trade and emigration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 106, 8239-8244. |

| [9] | Briggs JC (2003) Marine centres of origin as evolutionary engines. Journal of Biogeography, 30, 1-18. |

| [10] |

Cánovas FG, Mota CF, Serrão EA, Pearson GA (2011) Driving south: A multi-gene phylogeny of the brown algal family Fucaceae reveals relationships and recent drivers of a marine radiation. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 11, 371.

DOI PMID |

| [11] | Catarino MD, Silva A, Cardoso SM (2018) Phycochemical constituents and biological activities of Fucus spp. Marine Drugs, 16, 249. |

| [12] | Coleman MA, Brawley SH (2005) Are life history characteristics good predictors of genetic diversity and structure? A case study of the intertidal alga Fucus spiralis (Heterokontophyta; Phaeophyceae). Journal of Phycology, 41, 753-762. |

| [13] | Coyer JA, Hoarau G, Oudot-Le Secq MP, Stam WT, Olsen JL (2006) A mtDNA-based phylogeny of the brown algal genus Fucus (Heterokontophyta; Phaeophyta). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 39, 209-222. |

| [14] | Coyer JA, Hoarau G, Schaik JV, Luijckx P, Olsen JL (2011) Trans-Pacific and trans-Arctic pathways of the intertidal macroalga Fucus distichus L. reveal multiple glacial refugia and colonizations from the North Pacific to the North Atlantic. Journal of Biogeography, 38, 756-771. |

| [15] |

Coyer JA, Hoarau G, Sjøtun K, Olsen JL (2008) Being abundant is not enough: A decrease in effective population size over eight generations in a Norwegian population of the seaweed, Fucus serratus. Biology Letters, 4, 755-757.

DOI PMID |

| [16] |

Coyer JA, Peters AF, Stam WT, Olsen JL (2003) Post-ice age recolonization and differentiation of Fucus serratus L. (Fucaceae: Phaeophyta) populations in Northern Europe. Molecular Ecology, 12, 1817-1829.

DOI PMID |

| [17] |

Cumashi A, Ushakova NA, Preobrazhenskaya ME, D’Incecco A, Piccoli A, Totani L, Tinari N, Morozevich GE, Berman AE, Bilan MI (2007) A comparative study of the anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant, antiangiogenic, and antiadhesive activities of nine different fucoidans from brown seaweeds. Glycobiology, 17, 541-552.

DOI PMID |

| [18] | Dyke AS, Prest VK (1987) Late Wisconsinan and Holocene history of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Géographie Physique et Quaternaire, 41, 237-263. |

| [19] |

Engel CR, Daguin C, Serräo E (2005) Genetic entities and mating system in hermaphroditic Fucus spiralis and its close dioecious relative F. vesiculosus (Fucaceae, Phaeophyceae). Molecular Ecology, 14, 2033-2046.

DOI PMID |

| [20] |

Excoffier L, Lischer HEL (2010) Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Molecular Ecology Resources, 10, 564-567.

DOI PMID |

| [21] | Fan RY, Gao Y, Xie XN, Gao YM, Su M (2024) Ichnological analysis of glacially-influenced sediments from the late Pleistocene to Holocene on the southeastern Canadian margin: Implications for palaeoclimate and palaeoceanography. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 651, 112401. |

| [22] |

Fenberg PB, Posbic K, Hellberg ME (2014) Historical and recent processes shaping the geographic range of a rocky intertidal gastropod: Phylogeography, ecology, and habitat availability. Ecology and Evolution, 4, 3244-3255.

DOI PMID |

| [23] |

Ferreira JG, Arenas F, Marínez B, Hawkins SJ, Jenkins SR (2014) Physiological response of fucoid algae to environmental stress: Comparing range centre and southern populations. New Phytologist, 202, 1157-1172.

DOI PMID |

| [24] | Frenzel B, Pécsi M, Velichko AA (1992) Atlas of Paleoclimates and Paleoenvironments of the Northern Hemisphere: Late Pleistocene-Holocene. Geographical Research Institute, Hungarian Academy of Science, Budapest. |

| [25] | Hiscock K, Southward A, Tittley I, Hawkins S (2004) Effects of changing temperature on benthic marine life in Britain and Ireland. Aquatic Conservation, 14, 333-362. |

| [26] |

Hoarau G, Coyer JA, Veldsink JH, Stam WT, Olsen JL (2007) Glacial refugia and recolonization patterns in the brown seaweed Fucus serratus. Molecular Ecology, 16, 3606-3616.

DOI PMID |

| [27] | Hu ZM, Du YQ, Liang YS, Zhong KL, Zhang J (2021) Phylogeographic patterns and genetic connectivity of marine plants: A review. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 52, 418-432. (in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [胡自民, 杜玉群, 梁延硕, 钟凯乐, 张杰 (2021) 海洋植物谱系地理模式与遗传连通性研究进展. 海洋与湖沼, 52, 418-432.] | |

| [28] | Hu ZM, Guiry MD, Critchley AT, Duan DL (2010) Phylogeographic patterns indicate trans-Atlantic migration from Europe to North America in the red seaweed Chondrus crispus (Gigartinales, Rhodophyta). Journal of Phycology, 46, 889-900. |

| [29] | Hu ZM, Kantachumpoo A, Liu RY, Sun ZM, Yao JT, Komatusu T, Uwai S, Duan DL (2018) A late Pleistocene marine glacial refugium in the south-west of Hainan Island, China: Phylogeographical insights from the brown alga Sargassum polycystum. Journal of Biogeography, 45, 355-366. |

| [30] | Hu ZM, Uwai S, Yu SH, Komatsu T, Ajisaka T, Duan DL (2011) Phylogeographic heterogeneity of the brown macroalga Sargassum horneri (Fucaceae) in the northwestern Pacific in relation to late Pleistocene glaciation and tectonic configurations. Molecular Ecology, 20, 3894-3909. |

| [31] |

Jueterbock A, Smolina I, Coyer JA, Hoarau G (2016) The fate of the Arctic seaweed Fucus distichus under climate change: an ecological niche modelling approach. Ecology and Evolution, 6, 1712-1724.

DOI PMID |

| [32] | Kelly DW, Macisaac HJ, Heath DD, Crandall K (2009) Vicariance and dispersal effects on phylogeographic structure and speciation in a widespread estuarine invertebrate. Evolution, 60, 257-267. |

| [33] |

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K (2018) MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1547-1549.

DOI PMID |

| [34] | Laughinghouse HD IV, Müller KM, Adey WH, Lara Y, Young R, Johnson G (2015) Evolution of the northern rockweed, Fucus distichus, in a regime of glacial cycling: Implications for benthic algal phylogenetics. PLoS ONE, 10, e0143795. |

| [35] | Lindeberg MR, Lindstrom SC (2010) Field Guide to Seaweeds of Alaska. Fairbanks, Alaska. |

| [36] | Lindstrom SC (2001) The Bering Strait connection: Dispersal and speciation in boreal macroalgae. Journal of Biogeography, 28, 243-251. |

| [37] | Liu YJ, Zhong KL, Jueterbock A, Satoshi S, Choi HG, Weinberger F, Assis J, Hu ZM (2022) The invasive alga Gracilaria vermiculophylla in the native northwest Pacific under ocean warming: Southern genetic consequence and northern range expansion. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 983685. |

| [38] | Maggs CA, Castilho R, Foltz DW, Henzler C, Jolly MT, Kelly J, Olsen JL, Perez KE, Stam WT, Vainola R, Viard F, Wares JP (2008) Evaluating signatures of glacial refugia for north Atlantic benthic marine taxa. Ecology, 89, S108-S122. |

| [39] | Marincovich L, Gladenov A (1999) Evidence for an earlier opening of the Bering Strait. Nature, 397, 149-151. |

| [40] | McCabe MK, Konar B (2021) Influence of environmental attributes on intertidal community structure in glacial estuaries. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 194, 104986. |

| [41] | Norton TA (1992) Dispersal by macroalgae. British Phycological Journal, 27, 293-301. |

| [42] | Olsen JL, Zechman FW, Hoarau G, Coyer JA, Stam WT, Valero M, Åberg P (2010) The phylogeographic architecture of the fucoid seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum: An intertidal ‘marine tree’ and survivor of more than one glacial- interglacial cycle. Journal of Biogeography, 37, 842-856. |

| [43] | Pearson G, Brawley S (1996) Reproductive ecology of Fucus distichus (Phaeophyceae): An intertidal alga with successful external fertilization. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 143, 211-223. |

| [44] |

Pereyra RT, Bergström L, Kautsky L, Johannesson K (2009) Rapid speciation in a newly opened postglacial marine environment, the Baltic Sea. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 9, 70.

DOI PMID |

| [45] | Popescu SM, Suc JP, Fauquette S, Bessedik M, Jimenez- Moreno G, Robin C, Labrousse L (2021) Mangrove distribution and diversity during three Cenozoic thermal maxima in the Northern Hemisphere (pollen records from the Arctic-North Atlantic-Mediterranean regions). Journal of Biogeography, 48, 2771-2784. |

| [46] | Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, Sánchez-Gracia A (2017) DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 34, 3299-3302. |

| [47] | Serräo E, Alice L, Brawley S (1999) Evolution of the Fucaceae (Phaeophyceae) inferred from nrDNA-ITS. Journal of Phycology, 35, 382-394. |

| [48] | Serräo EA, Kautsky L, Lifvergren T, Brawley S (1997) Gamete dispersal and pre-recruitment mortality in Baltic Fucus vesiculosus. Phycologia (Suppl.), 36, 101-102. |

| [49] | Shaw J (2003) Submarine moraines in Newfoundland coastal waters: Implications for the deglaciation of Newfoundland and adjacent areas. Quaternary International, 99/100, 115-134. |

| [50] | Shaw J (2006) Palaeogeography of Atlantic Canadian continental shelves from the last glacial maximum to the present, with an emphasis on Flemish Cap. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science, 37, 119-126. |

| [51] | Shaw J, Piper DJW, Fader GBJ, King EL, Todd BJ, Bell T, Batterson MJ, Liverman DGE (2006) A conceptual model of the deglaciation of Atlantic Canada. Quaternary Science Reviews, 25, 2059-2081. |

| [52] | Signore AV, Morrison PR, Brauner CJ, Fago A, Weber RE, Campbell KL (2023) Evolution of an extreme hemoglobin phenotype contributed to the sub-Arctic specialization of extinct Steller’s sea cows. eLife, 12, e85414. |

| [53] | Smolina I, Kollias S, Jueterbock A, Coyer JA, Hoarau G (2016) Variation in thermal stress response in two populations of the brown seaweed, Fucus distichus, from the Arctic and subarctic intertidal. Royal Society Open Science, 3, 150429. |

| [54] | Song XH, Assis J, Zhang J, Gao X, Choi HG, Duan DL, Serrao EA, Hu ZM (2021) Climate-induced range shifts shaped the present and threaten the future genetic variability of a marine brown alga in the Northwest Pacific. Evolutionary Applications, 14, 1867-1879. |

| [55] | Song XK, Gravili C, Wang JJ, Deng YC, Wang YQ, Fang L, Lin HS, Wang SQ, Zheng YT, Lin JH (2016) A new deep-sea hydroid (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa) from the Bering Sea Basin reveals high genetic relevance to Arctic and adjacent shallow-water species. Polar Biology, 39, 461-471. |

| [56] | Sukhoveeva MV, Podkorytova AV (2006) Commercial Algae and Grasses of the Seas of the Far East: Biology, Distribution, Stocks, Processing Technology. Tinro-Center, Vladivostok. |

| [57] | Svendsen H, Beszczynska-Møller A, Hagen JO, Lefauconnier B, Tverberg V, Gerland S (2002) The physical environment of Kongsfjorden-Krossfjorden, an Arctic fjord system in Svalbard. Polar Research, 21, 133-166. |

| [58] |

Tatarenkov A, Bergström L, Jönsson RB, Serrao EA, Kautsky L, Johannesson K (2005) Intriguing asexual life in marginal populations of the brown seaweed Fucus vesiculosus. Molecular Ecology, 14, 647-651.

DOI PMID |

| [59] | Umanzor S, Sandoval-Gil JM, Conitz J (2023) Ecophysiological responses of the intertidal seaweed Fucus distichus to temperature changes and reduced light driven by tides and glacial input. Estuaries and Coasts, 46, 1269-1279. |

| [60] | van Oppen MJH, Draisma SGA, Olsen JL, Stam WT (1995) Multiple trans-Arctic passages in the red alga Phycodrys rubens: Evidence from nuclear rDNA ITS sequences. Marine Biology, 123, 179-188. |

| [61] | Vermeij GJ (2005) From Europe to America:Pliocene to recent trans-Atlantic expansion of cold-water North Atlantic molluscs. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272, 2545-2550. |

| [62] | Wahl M, Jormalaineny V, Erikssonz BK, Coyer JA, Molis M, Schubert H, Dethier M, Karez R, Kruse I, Lenz M, Pearson G, Rohde S, Wikström SA, Olsen JL (2011) Stress ecology in Fucus:Abiotic, biotic and genetic interactions. In: Advances in Marine Biology (ed. Lesser M), pp. 37-105. Academic Press, Oxford. |

| [63] |

Wares JP, Cunningham CW (2001) Phylogeography and historical ecology of the North Atlantic intertidal. Evolution, 55, 2455-2469.

DOI PMID |

| [64] | Weslawski JM, Wiktor J, Kotwicki L (2010) Increase in biodiversity in the Arctic rocky littoral, Sorkappland, Svalbard, after 20 years of climate warming. Marine Biodiversity, 40, 123-130. |

| [65] | Zhong KL, Song XH, Choi HG, Satoshi S, Weinberger F, Draisma SGA, Duan DL, Hu ZM (2020) MtDNA-based phylogeography of the red alga Agarophyton vermiculophyllum (Gigartinales, Rhodophyta) in the native Northwest Pacific. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7, 366. |

| [1] | Jinbo Xu, Yaqian Cui, Yuan Wang, Weibo Wang, Feng Liu, Guanglong Wang, Jingjing Hu, Dunzhu Pubu, Duoji Bianba, Zeng Dan, Kai Hu, Xiaochuan Wang, Gang Song, Yonglei Lü, Zhixin Wen. Habitat suitability evaluation of Macaca leucogenys in the Xizang Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon National Nature Reserve [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2025, 33(7): 24493-. |

| [2] | Gu Jingjing, Liu Yizhuo, Su Yang. The functions and challenges of grass-roots local governments in fulfilling the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework—A comparative analysis with the objectives of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2025, 33(3): 24585-. |

| [3] | Qi Wu, Xiaoqing Zhang, Yuting Yang, Yibo Zhou, Yi Ma, Daming Xu, Xingfeng Si, Jian Wang. Spatio-temporal changes in biodiversity of epiphyllous liverworts in Qingyuan Area of Qianjiangyuan-Baishanzu National Park, Zhejiang Province [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2024, 32(4): 24010-. |

| [4] | Kexin Cao, Jingwen Wang, Guo Zheng, Pengfeng Wu, Yingbin Li, Shuyan Cui. Effects of precipitation regime change and nitrogen deposition on soil nematode diversity in the grassland of northern China [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2024, 32(3): 23491-. |

| [5] | Li Feng. On synergistic governance of biodiversity and climate change in the perspective of international law [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2023, 31(7): 23110-. |

| [6] | Xue Yao, Xing Chen, Zun Dai, Kun Song, Shichen Xing, Hongyu Cao, Lu Zou, Jian Wang. Importance of collection strategy on detection probability and species diversity of epiphyllous liverworts [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2023, 31(4): 22685-. |

| [7] | Wenwen Shao, Guozhen Fan, Zhizhou He, Zhiping Song. Phenotypic plasticity and local adaptation of Oryza rufipogon revealed by common garden trials [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2023, 31(3): 22311-. |

| [8] | Jiawen Sang, Chuangye Song, Ningxia Jia, Yuan Jia, Changcheng Liu, Xianguo Qiao, Lin Zhang, Weiying Yuan, Dongxiu Wu, Linghao Li, Ke Guo. Vegetation survey and mapping on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2023, 31(3): 22430-. |

| [9] | Jinzhou Wang, Jing Xu. Nature-based solutions for addressing biodiversity loss and climate change: Progress, challenges and suggestions [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2023, 31(2): 22496-. |

| [10] | Jiman Li, Nan Jin, Maogang Xu, Jusong Huo, Xiaoyun Chen, Feng Hu, Manqiang Liu. Effects of earthworm on tomato resistance under different drought levels [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2022, 30(7): 21488-. |

| [11] | Ruiliang Zhu, Xiaoying Ma, Chang Cao, Ziyin Cao. Advances in research on bryophyte diversity in China [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2022, 30(7): 22378-. |

| [12] | Kuiling Zu, Zhiheng Wang. Research progress on the elevational distribution of mountain species in response to climate change [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2022, 30(5): 21451-. |

| [13] | Xin Jing, Shengjing Jiang, Huiying Liu, Yu Li, Jin-Sheng He. Complex relationships and feedback mechanisms between climate change and biodiversity [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2022, 30(10): 22462-. |

| [14] | Huijie Qiao, Junhua Hu. Reconstructing community assembly using a numerical simulation model [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2022, 30(10): 22456-. |

| [15] | Dan Zhang, Songmei Ma, Bo Wei, Chuncheng Wang, Lin Zhang, Han Yan. Historical distribution pattern and driving mechanism of Haloxylon in China [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2022, 30(1): 21192-. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||

Copyright © 2022 Biodiversity Science

Editorial Office of Biodiversity Science, 20 Nanxincun, Xiangshan, Beijing 100093, China

Tel: 010-62836137, 62836665 E-mail: biodiversity@ibcas.ac.cn ![]()