Biodiv Sci ›› 2024, Vol. 32 ›› Issue (11): 24276. DOI: 10.17520/biods.2024276 cstr: 32101.14.biods.2024276

• Special Feature: Biological Invasion • Previous Articles Next Articles

Congcong Du1,2,3( ), Xueyu Feng1,2,3, Zhilin Chen1,2,3,*(

), Xueyu Feng1,2,3, Zhilin Chen1,2,3,*( )

)

Received:2024-06-30

Accepted:2024-11-08

Online:2024-11-20

Published:2024-12-10

Contact:

E-mail: Supported by:Congcong Du, Xueyu Feng, Zhilin Chen. The reducing of climate niche differences in the bridgehead effect promotes the invasion of Solenopsis invicta[J]. Biodiv Sci, 2024, 32(11): 24276.

| 生物气候变量 Bioclimatic variables | 南美 South America | 美国 United States | 中国 China |

|---|---|---|---|

| 平均气温日较差 Mean diurnal range (Bio2) | + | + | + |

| 等温性 Isothermality (Bio3) | - | + | - |

| 温度季节性 Temperature seasonality (Bio4) | + | - | + |

| 最热月最高温 Max temperature of warmest month (Bio5) | - | + | + |

| 最冷月最低温 Min temperature of coldest month (Bio6) | + | - | + |

| 最湿季平均温 Mean temperature of wettest quarter (Bio8) | + | + | + |

| 最干季平均温 Mean temperature of driest quarter (Bio9) | - | + | - |

| 最暖季平均温 Mean temperature of warmest quarter (Bio10) | - | + | + |

| 最冷季平均温 Mean temperature of coldest quarter (Bio11) | - | + | - |

| 年降水量 Annual precipitation (Bio12) | + | + | + |

| 最湿月降水量 Precipitation of wettest month (Bio13) | + | - | - |

| 最干月降水量 Precipitation of driest month (Bio14) | + | + | + |

| 最冷季降水量 Precipitation of coldest quarter (Bio18) | + | + | + |

Table 1 Environmental variables in different study areas

| 生物气候变量 Bioclimatic variables | 南美 South America | 美国 United States | 中国 China |

|---|---|---|---|

| 平均气温日较差 Mean diurnal range (Bio2) | + | + | + |

| 等温性 Isothermality (Bio3) | - | + | - |

| 温度季节性 Temperature seasonality (Bio4) | + | - | + |

| 最热月最高温 Max temperature of warmest month (Bio5) | - | + | + |

| 最冷月最低温 Min temperature of coldest month (Bio6) | + | - | + |

| 最湿季平均温 Mean temperature of wettest quarter (Bio8) | + | + | + |

| 最干季平均温 Mean temperature of driest quarter (Bio9) | - | + | - |

| 最暖季平均温 Mean temperature of warmest quarter (Bio10) | - | + | + |

| 最冷季平均温 Mean temperature of coldest quarter (Bio11) | - | + | - |

| 年降水量 Annual precipitation (Bio12) | + | + | + |

| 最湿月降水量 Precipitation of wettest month (Bio13) | + | - | - |

| 最干月降水量 Precipitation of driest month (Bio14) | + | + | + |

| 最冷季降水量 Precipitation of coldest quarter (Bio18) | + | + | + |

| 入侵方向 Invasion direction | 总变化距离 Schoener’s D | Hellinger距离 Hellinger’s I |

|---|---|---|

| 美国入侵至中国 United States to China | 0.34 | 0.51 |

| 南美洲入侵至美国 South America to United States | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| 南美洲入侵至中国 South America to China | 0.01 | 0.05 |

Table 2 Climatic niche overlap between native range (South America), bridgehead range (United States) and secondary invaded range (China) of Solenopsis invicta

| 入侵方向 Invasion direction | 总变化距离 Schoener’s D | Hellinger距离 Hellinger’s I |

|---|---|---|

| 美国入侵至中国 United States to China | 0.34 | 0.51 |

| 南美洲入侵至美国 South America to United States | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| 南美洲入侵至中国 South America to China | 0.01 | 0.05 |

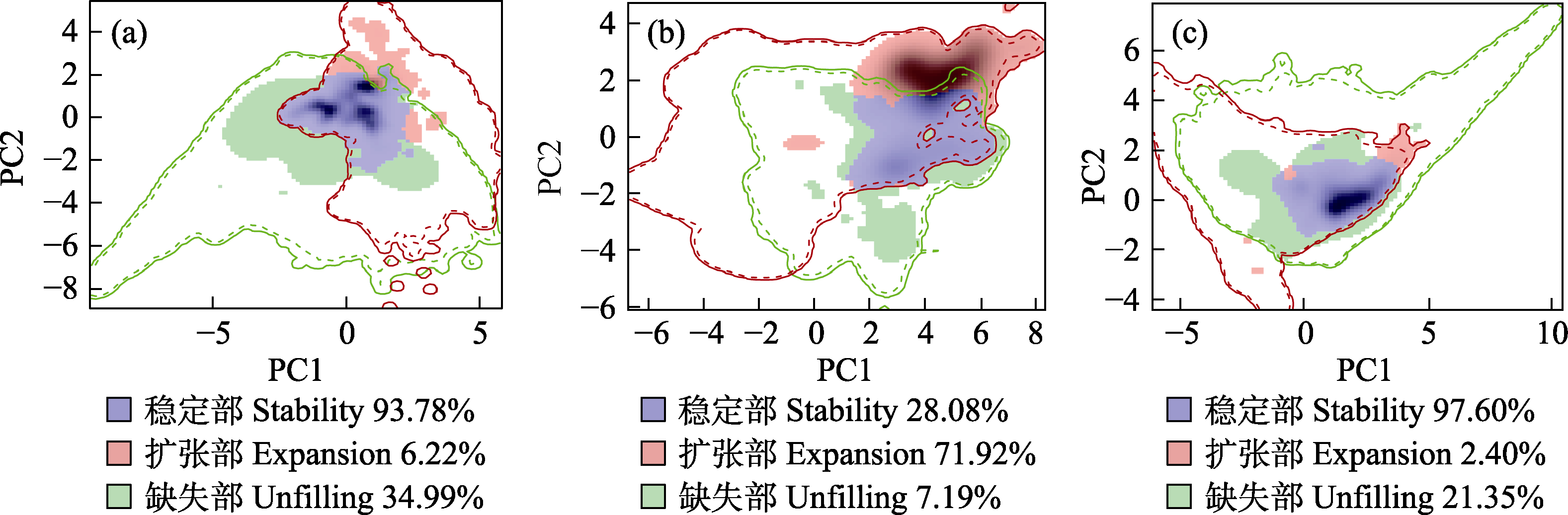

Fig. 1 Climatic ecotope dynamics between native range (South America), bridgehead range (United States) and secondary invaded range (China) of Solenopsis invicta. (a) Between native range and bridgehead range; (b) Between bridgehead range and secondary invaded range; (c) Between native range and secondary invaded range.

| [1] |

Ascunce MS, Yang CC, Oakey J, Calcaterra L, Wu WJ, Shih CJ, Goudet J, Ross KG, Shoemaker D (2011) Global invasion history of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Science, 331, 1066-1068.

DOI PMID |

| [2] | Bates OK, Bertelsmeier C (2021) Climatic niche shifts in introduced species. Current Biology, 31, R1252-R1266. |

| [3] | Bertelsmeier C, Keller L (2018) Bridgehead effects and role of adaptive evolution in invasive populations. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 33, 527-534. |

| [4] | Bertelsmeier C, Ollier S (2021) Bridgehead effects distort global flows of alien species. Diversity and Distributions, 27, 2180-2189. |

| [5] | Bertelsmeier C, Ollier S, Liebhold A, Keller L (2017) Recent human history governs global ant invasion dynamics. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1, 0184. |

| [6] | Boudjelas S, Browne M, De Poorter M, Lowe S (2000) 100 of the world’s worst invasive alien species: A selection from the Global Invasive Species Database. The Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG), Auckland, New Zealand. |

| [7] | Britnell JA, Zhu YC, Kerley GIH, Shultz S (2023) Ecological marginalization is widespread and increases extinction risk in mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 120, e2205315120. |

| [8] | Broennimann O, Fitzpatrick MC, Pearman PB, Petitpierre B, Pellissier L, Yoccoz NG, Thuiller W, Fortin MJ, Randin C, Zimmermann NE, Graham CH, Guisan A (2012) Measuring ecological niche overlap from occurrence and spatial environmental data. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 21, 481-497. |

| [9] | Brooks HB, Guzman-Hernandez I, Beasley DE (2023) Ant biodiversity in a temperate urban environment. Bios, 93, 117-123. |

| [10] | Chen JSC, Shen CH, Lee HJ (2006) Monogynous and polygynous red imported fire ants, Solenopsis invicta Buren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), in Taiwan. Environmental Entomology, 35, 167-172. |

| [11] | Clavero M, García-Berthou E (2005) Invasive species are a leading cause of animal extinctions. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 20, 110. |

| [12] |

Colautti RI, Lau JA (2015) Contemporary evolution during invasion: Evidence for differentiation, natural selection, and local adaptation. Molecular Ecology, 24, 1999-2017.

DOI PMID |

| [13] | Du SJ, Guo JY, Zhao HX, Wan FH, Liu WX (2023) Research progresses on management of invasive alien species in China. Plant Protection, 49, 410-418, 440. (in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [杜素洁, 郭建洋, 赵浩翔, 万方浩, 刘万学 (2023) 近十年我国入侵生物预防与监控研究. 植物保护, 49, 410-418, 440.] | |

| [14] | Elton CS (1958) The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants. Springer, Boston. |

| [15] |

Enders M, Havemann F, Ruland F, Bernard-Verdier M, Catford JA, Gómez-Aparicio L, Haider S, Heger T, Kueffer C, Kühn I, Meyerson LA, Musseau C, Novoa A, Ricciardi A, Sagouis A, Schittko C, Strayer DL, Vilà M, Essl F, Hulme PE, van Kleunen M, Kumschick S, Lockwood JL, Mabey AL, McGeoch MA, Palma E, Pyšek P, Saul WC, Yannelli FA, Jeschke JM (2020) A conceptual map of invasion biology: Integrating hypotheses into a consensus network. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 29, 978-991.

DOI PMID |

| [16] | Garnas RJ, Auger-Rozenberg MA, Roques A, Bertelsmeier C, Wingfield MJ, Saccaggi DL, Roy HE, Slippers B (2016) Complex patterns of global spread in invasive insects: Eco-evolutionary and management consequences. Biological Invasions, 18, 935-952. |

| [17] | Holway DA, Lach L, Suarez AV, Tsutsui ND, Case TJ (2002) The causes and consequences of ant invasions. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 33, 181-233. |

| [18] | Hong YH, He YH, Lin ZQ, Du YB, Chen SN, Han LX, Zhang Q, Gu SM, Tu WS, Hu SW, Yuan ZY, Liu X (2022) Complex origins indicate a potential bridgehead introduction of an emerging amphibian invader (Eleutherodactylus planirostris) in China. NeoBiota, 77, 23-37. |

| [19] | Hulme M (2009) Why We Disagree about Climate Change:Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. |

| [20] | King JR, Tschinkel WR (2006) Experimental evidence that the introduced fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, does not competitively suppress co-occurring ants in a disturbed habitat. Journal of Animal Ecology, 75, 1370-1378. |

| [21] |

Krueger-Hadfield SA, Kollars NM, Strand AE, Byers JE, Shainker SJ, Terada R, Greig TW, Hammann M, Murray DC, Weinberger F, Sotka EE (2017) Genetic identification of source and likely vector of a widespread marine invader. Ecology and Evolution, 7, 4432-4447.

DOI PMID |

| [22] | Li M, Zhao HX, Xian XQ, Zhu JQ, Chen BX, Jia T, Wang R, Liu WX (2023) Geographical distribution pattern and ecological niche of Solenopsis invicta Buren in China under climate change. Diversity, 15, 607. |

| [23] | Li XL (2020) Risk and countermeasures of red imported fire ant epidemic in Wuxuan County. South China Agriculture, 14(24), 15-16. (in Chinese) |

| [李旭林 (2020) 武宣县农区红火蚁疫情扩散风险及应对措施探讨. 南方农业, 14(24), 15-16.] | |

| [24] | Li YM, Liu X, Li XP, Petitpierre B, Guisan A (2014) Residence time, expansion toward the equator in the invaded range and native range size matter to climatic niche shifts in non-native species. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 23, 1094-1104. |

| [25] | Lieurance D, Canavan S, Behringer DC, Kendig AE, Minteer CR, Reisinger LS, Romagosa CM, Flory SL, Lockwood JL, Anderson PJ, Baker SM, Bojko J, Bowers KE, Canavan K, Carruthers K, Daniel WM, Gordon DR, Hill JE, Howeth JG, Iannone BV III, Jennings L, Gettys LA, Kariuki EM, Kunzer JM, Laughinghouse HDI, Mandrak NE, McCann S, Morawo T, Morningstar CR, Neilson M, Petri T, Pfingsten IA, Reed RN, Walters LJ, Wanamaker C (2023) Identifying invasive species threats, pathways, and impacts to improve biosecurity. Ecosphere, 14, e4711. |

| [26] | Liu CL, Wolter C, Xian WW, Jeschke JM (2020) Most invasive species largely conserve their climatic niche. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 117, 23643-23651. |

| [27] | Lu YY, Zeng L, Xu YJ, Liang GW, Wang L (2019) Research progress of invasion biology and management of red imported fire ant. Journal of South China Agricultural University, 40(5), 149-160. (in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [陆永跃, 曾玲, 许益镌, 梁广文, 王磊 (2019) 外来物种红火蚁入侵生物学与防控研究进展. 华南农业大学学报, 40(5), 149-160.] | |

| [28] | Lü LH, He YR, Liu J, Liu XY, Vinson SB (2006) Invasion, diffusion, biology and harm of red imported fire ants. Guangdong Agricultural Sciences, (5), 3-11. (in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [吕利华, 何余容, 刘杰, 刘晓燕, Vinson SB (2006) 红火蚁的入侵、扩散、生物学及其危害. 广东农业科学, (5), 3-11.] | |

| [29] | McGeoch MA, Butchart SHM, Spear D, Marais E, Kleynhans EJ, Symes A, Chanson J, Hoffmann M (2010) Global indicators of biological invasion: Species numbers, biodiversity impact and policy responses. Diversity and Distributions, 16, 95-108. |

| [30] | Meyerson LA, Mooney HA (2007) Invasive alien species in an era of globalization. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 5, 199-208. |

| [31] | Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington, DC |

| [32] | Ni M, Deane DC, Li SP, Wu YT, Sui XH, Xu H, Chu CJ, He FL, Fang SQ (2021) Invasion success and impacts depend on different characteristics in non-native plants. Diversity and Distributions, 27, 1194-1207. |

| [33] | Paini DR, Sheppard AW, Cook DC, De Barro PJ, Worner SP, Thomas MB (2016) Global threat to agriculture from invasive species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 113, 7575-7579. |

| [34] | Pearson DE, Eren Ö, Ortega YK, Hierro JL, Karakuş B, Kala S, Bullington L, Lekberg Y (2022) Combining biogeographical approaches to advance invasion ecology and methodology. Journal of Ecology, 110, 2033-2045. |

| [35] | Pyšek P, Richardson DM (2010) Invasive species, environmental change and management, and health. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 35, 25-55. |

| [36] | Ricciardi A, Blackburn TM, Carlton JT, Dick JTA, Hulme PE, Iacarella JC, Jeschke JM, Liebhold AM, Lockwood JL, MacIsaac HJ, Pyšek P, Richardson DM, Ruiz GM, Simberloff D, Sutherland WJ, Wardle DA, Aldridge DC (2017) Invasion science: A horizon scan of emerging challenges and opportunities. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 32, 464-474. |

| [37] | Richardson DM, Pyšek P (2006) Plant invasions: Merging the concepts of species invasiveness and community invasibility. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, 30, 409-431. |

| [38] | Rödder D, Engler JO (2011) Quantitative metrics of overlaps in Grinnellian niches: Advances and possible drawbacks. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 20, 915-927. |

| [39] |

Shackleton RT, Richardson DM, Shackleton CM, Bennett B, Crowley SL, Dehnen-Schmutz K, Estévez RA, Fischer A, Kueffer C, Kull CA, Marchante E, Novoa A, Potgieter LJ, Vaas J, Vaz AS, Larson BMH (2019) Explaining people’s perceptions of invasive alien species: A conceptual framework. Journal of Environmental Management, 229, 10-26.

DOI PMID |

| [40] | Soberón J, Nakamura M (2009) Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 106, 19644-19650. |

| [41] | Soberón J, Peterson AT (2005) Interpretation of models of fundamental ecological niches and species’ distributional areas. Biodiversity Informatics, 2, 1-10. |

| [42] | Srivastava V, Lafond V, Griess VC (2019) Species distribution models (SDM): Applications, benefits and challenges in invasive species management. CABI Reviews, 2019, 1-13. |

| [43] | Tschinkel WR, King JR (2017) Ant community and habitat limit colony establishment by the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Functional Ecology, 31, 955-964. |

| [44] |

Tuohetahong Y, Lu RY, Guo RY, Gan F, Zhao FY, Ding S, Jin SS, Cui HF, Niu KS, Wang C, Duan WB, Ye XP, Yu XP (2024) Climate and land use/land cover changes increasing habitat overlap among endangered crested ibis and sympatric egret/heron species. Scientific Reports, 14, 20736.

DOI PMID |

| [45] | Vinson SB (1997) Insect life: Invasion of the red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). American Entomologist, 43, 23-39. |

| [46] |

Wang HJ, Wang H, Tao ZX, Ge QS (2018) Potential range expansion of the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) in China under climate change. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 28, 1965-1974.

DOI |

| [47] |

Wiens JJ, Ackerly DD, Allen AP, Anacker BL, Buckley LB, Cornell HV, Damschen EI, Jonathan Davies T, Grytnes JA, Harrison SP, Hawkins BA, Holt RD, McCain CM, Stephens PR (2010) Niche conservatism as an emerging principle in ecology and conservation biology. Ecology Letters, 13, 1310-1324.

DOI PMID |

| [48] | Xu CY, Zhang WJ, Lu BR, Chen JK (2001) Progress in studies on mechanisms of biological invasion. Biodiversity Science, 9, 430-438. (in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [徐承远, 张文驹, 卢宝荣, 陈家宽 (2001) 生物入侵机制研究进展. 生物多样性, 9, 430-438.] | |

| [49] | Xu YJ, Lu YY, Pan ZP, Zeng L, Liang GW (2009) Heat tolerance of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the mainland of China. Sociobiology, 54, 115. |

| [50] | Yang XM, Sun JT, Xue XF, Li JB, Hong XY (2012) Invasion genetics of the western flower thrips in China: Evidence for genetic bottleneck, hybridization and bridgehead effect. PLoS ONE, 7, e34567. |

| [1] | Xuejiao Yuan, Yuanyuan Zhang, Yanliang Zhang, Luyi Hu, Weiguo Sang, Zheng Yang, Qi Chen. Investigating the prediction ability of the species distribution model fitted with the historical distribution records of Chromolaena odorata [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2024, 32(11): 24288-. |

| [2] | Lixia Han, Yongjian Wang, Xuan Liu. Comparisons between non-native species invasion and native species range expansion [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2024, 32(1): 23396-. |

| [3] | Hong Chen, Xiaoqing Xian, Yixue Chen, Na Lin, Miaomiao Wang, Zhipeng Li, Jian Zhao. Spatial pattern and driving factors on the prevalence of red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) in island cities: A case study of Haitan Island, Fujian [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2023, 31(5): 22501-. |

| [4] | Jiajia Pu, Pingjun Yang, Yang Dai, Kexin Tao, Lei Gao, Yuzhou Du, Jun Cao, Xiaoping Yu, Qianqian Yang. Species identification and population genetic structure of non-native apple snails (Ampullariidea: Pomacea) in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2023, 31(3): 22346-. |

| [5] | Bo Wei, Linshan Liu, Changjun Gu, Haibin Yu, Yili Zhang, Binghua Zhang, Bohao Cui, Dianqing Gong, Yanli Tu. The climate niche is stable and the distribution area of Ageratina adenophora is predicted to expand in China [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2022, 30(8): 21443-. |

| [6] | Yanjie Liu, Wei Huang, Qiang Yang, Yu-Long Zheng, Shao-Peng Li, Hao Wu, Ruiting Ju, Yan Sun, Jianqing Ding. Research advances of plant invasion ecology over the past 10 years [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2022, 30(10): 22438-. |

| [7] | Jing Yan, Xiaoling Yan, Huiru Li, Cheng Du, Jinshuang Ma. Composition, time of introduction and spatial-temporal distribution of naturalized plants in East China [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2021, 29(4): 428-438. |

| [8] | Weiming He. Biological invasions: Are their impacts precisely knowable or not? [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2020, 28(2): 253-255. |

| [9] | Jiazhen Zhang, Chunlei Gao, Yan Li, Ping Sun, Zongling Wang. Species composition of dinoflagellates cysts in ballast tank sediments of foreign ships berthed in Jiangyin Port [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2020, 28(2): 144-154. |

| [10] | Wandong Yin, Mingke Wu, Baoliang Tian, Hongwei Yu, Qiyun Wang, Jianqing Ding. Effects of bio-invasion on the Yellow River basin ecosystem and its countermeasures [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2020, 28(12): 1533-1545. |

| [11] | Li Hanxi, Huang Xuena, Li Shiguo, Zhan Aibin. Environmental DNA (eDNA)-metabarcoding-based early monitoring and warning for invasive species in aquatic ecosystems [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2019, 27(5): 491-504. |

| [12] | Wensheng Yu, Yaolin Guo, Jiajia Jiang, Keke Sun, Ruiting Ju. Comparison of the life history of a native insect Laelia coenosa with a native plant Phragmites australis and an invasive plant Spartina alterniflora [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2019, 27(4): 433-438. |

| [13] | Shiguo Sun,Bin Lu,Xinmin Lu,Shuangquan Huang. On reproductive strategies of invasive plants and their impacts on native plants [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2018, 26(5): 457-467. |

| [14] | Yan Sun, Zhongshi Zhou, Rui Wang, Heinz Müller-Schärer. Biological control opportunities of ragweed are predicted to decrease with climate change in East Asia [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2017, 25(12): 1285-1294. |

| [15] | Ziyan Zhang, Zhijie Zhang, Xiaoyun Pan. Phenotypic plasticity of Alternanthera philoxeroides in response to shading: introduced vs. native populations [J]. Biodiv Sci, 2015, 23(1): 18-22. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||

Copyright © 2022 Biodiversity Science

Editorial Office of Biodiversity Science, 20 Nanxincun, Xiangshan, Beijing 100093, China

Tel: 010-62836137, 62836665 E-mail: biodiversity@ibcas.ac.cn