Biodiv Sci ›› 2025, Vol. 33 ›› Issue (4): 24554. DOI: 10.17520/biods.2024554 cstr: 32101.14.biods.2024554

• Original Papers: Plant Diversity • Previous Articles Next Articles

Wang Shunyu1,2( ), Li Yang1,2(

), Li Yang1,2( ), Lü Xiaoqin1,3(

), Lü Xiaoqin1,3( ), Li Xin1(

), Li Xin1( ), Fan Quanxiu1(

), Fan Quanxiu1( ), Wang Xiaoyue1,3,*(

), Wang Xiaoyue1,3,*( )(

)( )

)

Received:2024-12-09

Accepted:2025-03-03

Online:2025-04-20

Published:2025-03-10

Contact:

*E-mail: wang.xiaoyue1989@163.com

Supported by:Wang Shunyu, Li Yang, Lü Xiaoqin, Li Xin, Fan Quanxiu, Wang Xiaoyue. The color preference of bumblebee nectar robbing and its impact on the reproductive fitness of Lonicera calcarata[J]. Biodiv Sci, 2025, 33(4): 24554.

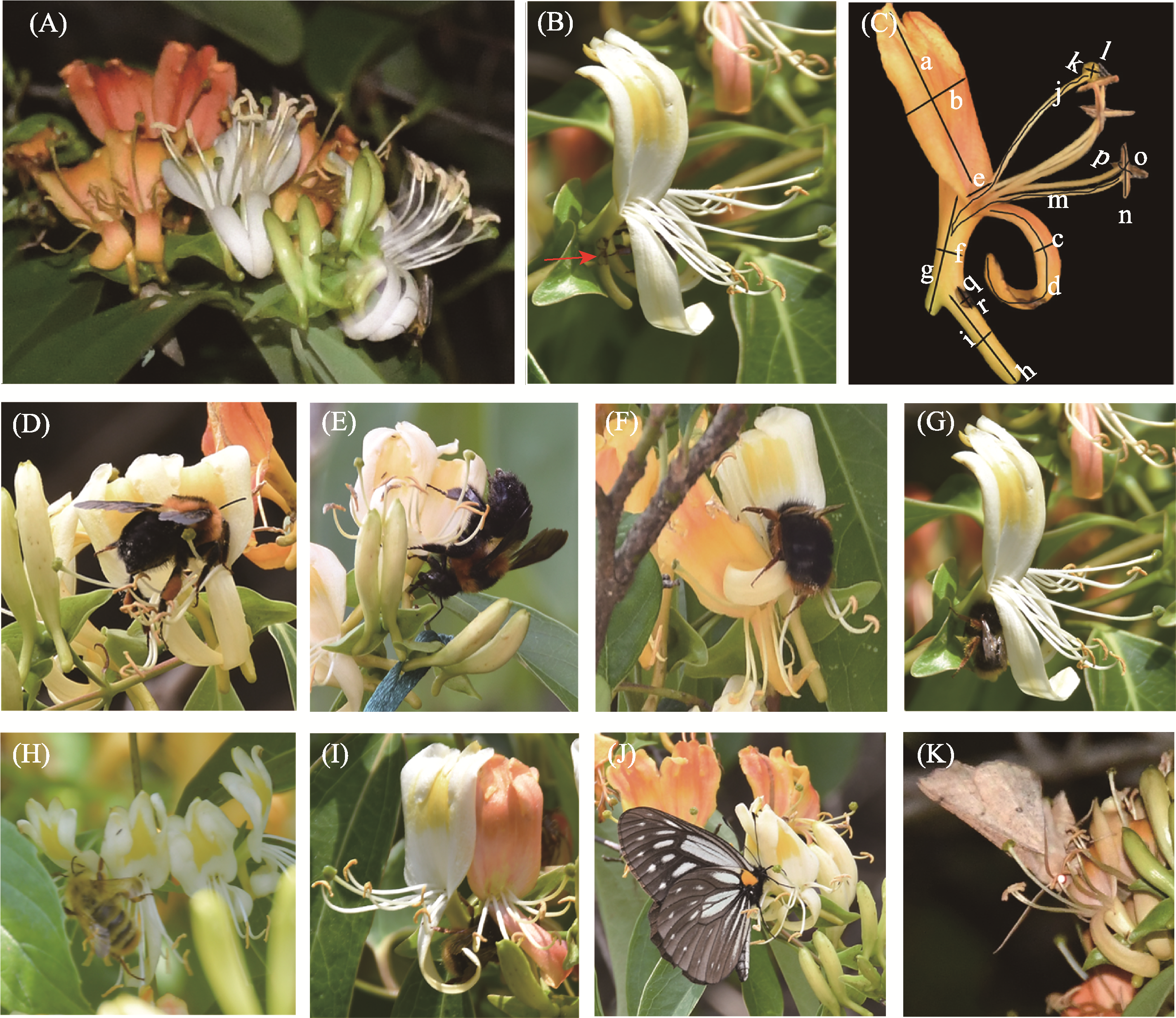

Fig. 1 Inflorescence and single flower of Lonicera calcarata and the visiting behavior of insects. A. White, yellow and orange-red flowers on the branch of L. calcarata; B. Nectar robbing phenomenon (using the white flower as an example, the hole marked with a red arrow); C. Diagram showing the measurement of floral traits (a, Upper lip length; b, Upper lip width; c, Lower lip length; d, Lower lip width; e, Floral opening diameter; f, Floral tube diamete; g, Floral tube depth; h, Nectar spur length; i, Nectar spur diameter; j, Pistil length; k, Stigma diameter; l, Stigma thickness; m, Stamen length; n, Anther length; o, Anther width; p, Anther thickness; q, Robbing hole’ length; r, Robbing hole’s width); D. Bombus melanurus forages the nectar through the corolla opening (legitimate visit); E. B. melanurus inserts its proboscis into the nectar spur’s base to rob nectar; F. B. eximius visits the flowers legitimately; G. B. eximius robs the nectar from the base of the nectar spur; H. B. sonani visits the flowers legitimately; I. B. sonani robs the nectar from the base of the nectar spur; J. Aporia agathon visits the flowers legitimately; K. Moths visits the flowers legitimately.

| 居群 Population | 位置 Location | 盗蜜率 Nectar robbing rate (%) | Wald χ2 | df | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 纬度 Latitude (°N) | 经度 Longitude (°E) | 海拔 Altitude (m) | 白色花 White flowers | 黄色花 Yellow flowers | 橘红色花 Orange-red flowers | ||||

| 1 | 23.14 | 104.81 | 1,939 | 15.81 ± 5.30b | 58.53 ± 13.36a | 60.88 ± 14.68a | 12.107 | 2 | 0.002 |

| 2 | 23.24 | 104.91 | 1,953 | 41.67 ± 22.05b | 89.71 ± 7.55a | 96.97 ± 3.03a | 12.895 | 2 | 0.002 |

| 3 | 23.16 | 104.82 | 1,920 | 32.82 ± 3.41b | 80.16 ± 8.40a | 83.33 ± 9.62a | 26.701 | 2 | < 0.001 |

| 4 | 23.19 | 104.86 | 1,930 | 16.90 ± 6.91b | 34.17 ± 19.73a | 75.35 ± 9.01a | 22.566 | 2 | < 0.001 |

| 5 | 23.29 | 104.76 | 1,941 | 11.97 ± 4.93b | 65.19 ± 17.12a | 72.50 ± 7.25a | 56.944 | 2 | < 0.001 |

| 6 | 22.69 | 105.76 | 1,817 | 35.42 ± 7.38b | 32.97 ± 7.67ab | 58.78 ± 8.58a | 8.746 | 2 | 0.013 |

| 7 | 22.19 | 105.16 | 1,761 | 0.00 ± 0.00c | 20.00 ± 16.33b | 38.89 ± 18.59a | 42.372 | 2 | < 0.001 |

Table 1 The locations of the seven wild populations of Lonicera calcarata and comparison of nectar robbing rates of white, yellow, and orange-red flowers in each population (generalized linear model analysis). Different lower case letters in the same row indicate significant differences in nectar robbing rate among the different color flowers.

| 居群 Population | 位置 Location | 盗蜜率 Nectar robbing rate (%) | Wald χ2 | df | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 纬度 Latitude (°N) | 经度 Longitude (°E) | 海拔 Altitude (m) | 白色花 White flowers | 黄色花 Yellow flowers | 橘红色花 Orange-red flowers | ||||

| 1 | 23.14 | 104.81 | 1,939 | 15.81 ± 5.30b | 58.53 ± 13.36a | 60.88 ± 14.68a | 12.107 | 2 | 0.002 |

| 2 | 23.24 | 104.91 | 1,953 | 41.67 ± 22.05b | 89.71 ± 7.55a | 96.97 ± 3.03a | 12.895 | 2 | 0.002 |

| 3 | 23.16 | 104.82 | 1,920 | 32.82 ± 3.41b | 80.16 ± 8.40a | 83.33 ± 9.62a | 26.701 | 2 | < 0.001 |

| 4 | 23.19 | 104.86 | 1,930 | 16.90 ± 6.91b | 34.17 ± 19.73a | 75.35 ± 9.01a | 22.566 | 2 | < 0.001 |

| 5 | 23.29 | 104.76 | 1,941 | 11.97 ± 4.93b | 65.19 ± 17.12a | 72.50 ± 7.25a | 56.944 | 2 | < 0.001 |

| 6 | 22.69 | 105.76 | 1,817 | 35.42 ± 7.38b | 32.97 ± 7.67ab | 58.78 ± 8.58a | 8.746 | 2 | 0.013 |

| 7 | 22.19 | 105.16 | 1,761 | 0.00 ± 0.00c | 20.00 ± 16.33b | 38.89 ± 18.59a | 42.372 | 2 | < 0.001 |

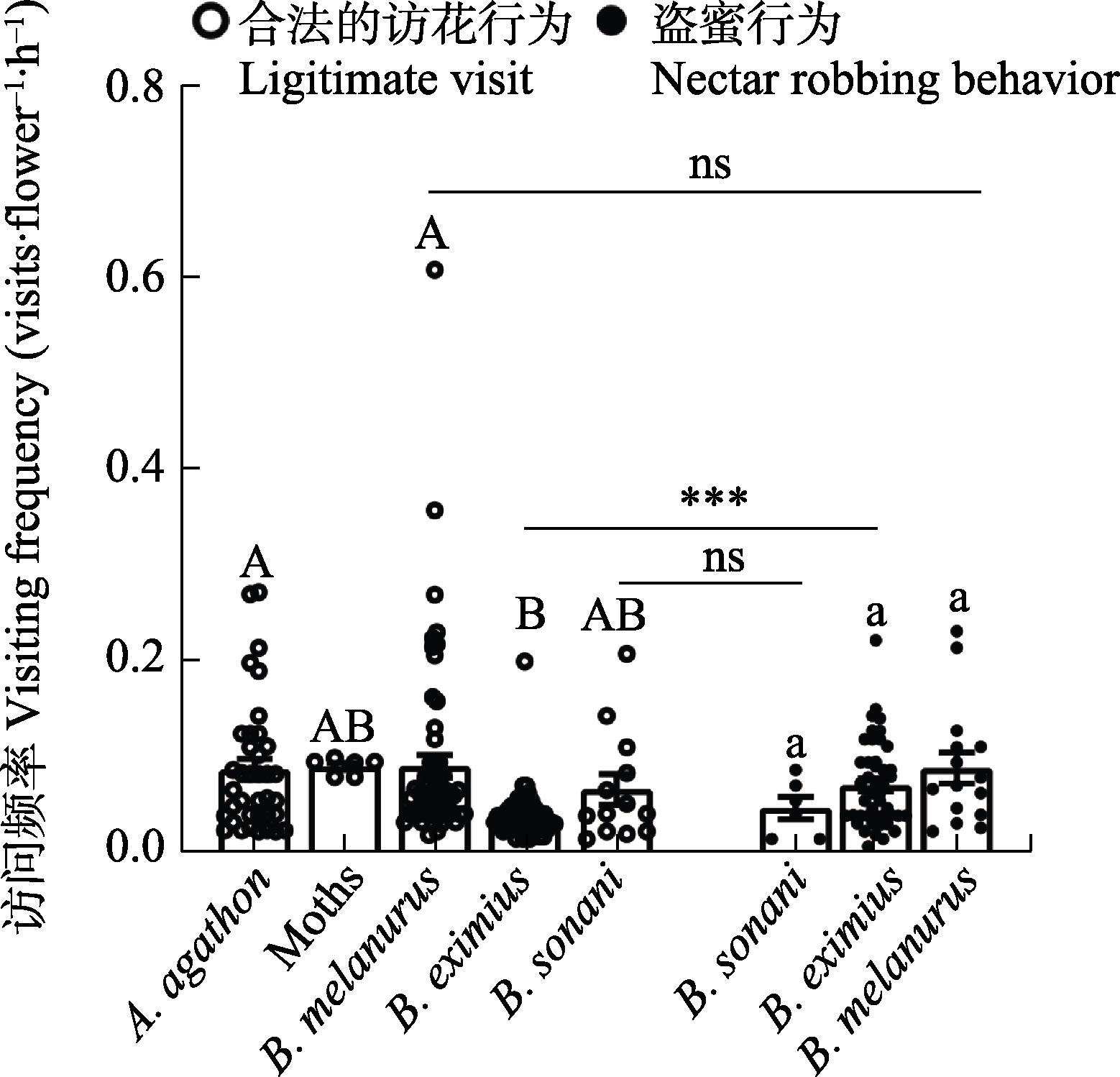

Fig. 2 Comparison of the frequency of legitimate visits (completing the pollination process) and nectar robbing behavior of Aporia agathon, moths, Bombus melanurus, B. eximius and B. sonani on Lonicera calcarata. Different uppercase letters indicate significant difference in the frequency of legitimate visits among different insects, while different lowercase letters indicate significant difference in the frequency of nectar robbing behavior among different insects. “ns” indicates no significant difference between the frequency of legitimate visit and nectar robbing behavior of the same insect (P > 0.05), while *** indicates that the nectar robbing frequency is significantly higher than the frequency of legitimate visits of the same insect (P < 0.001).

|

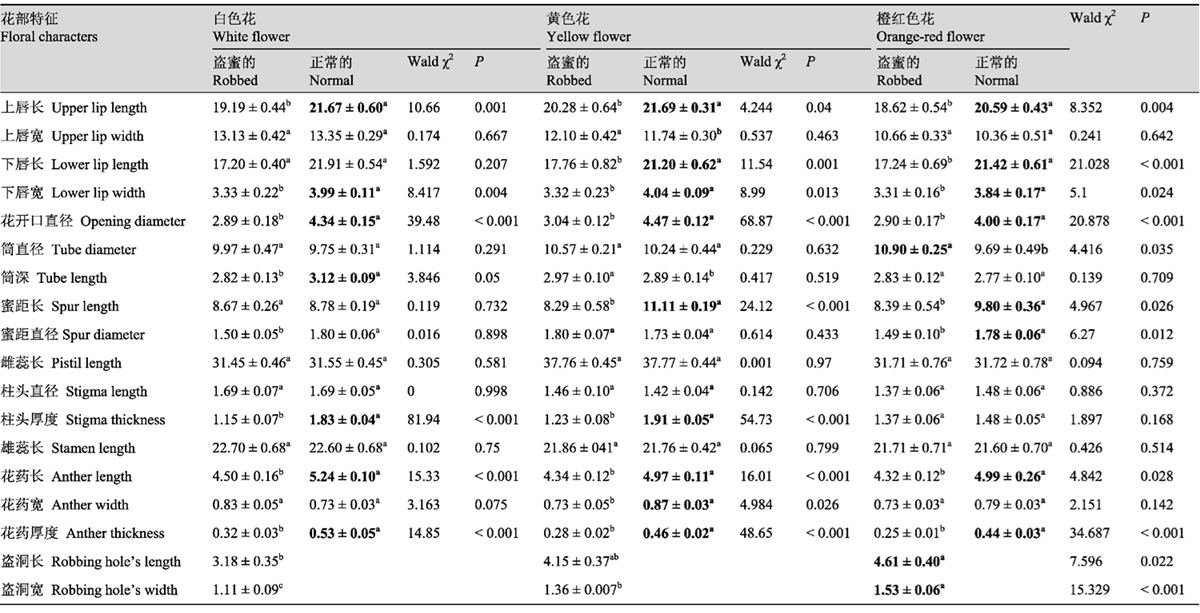

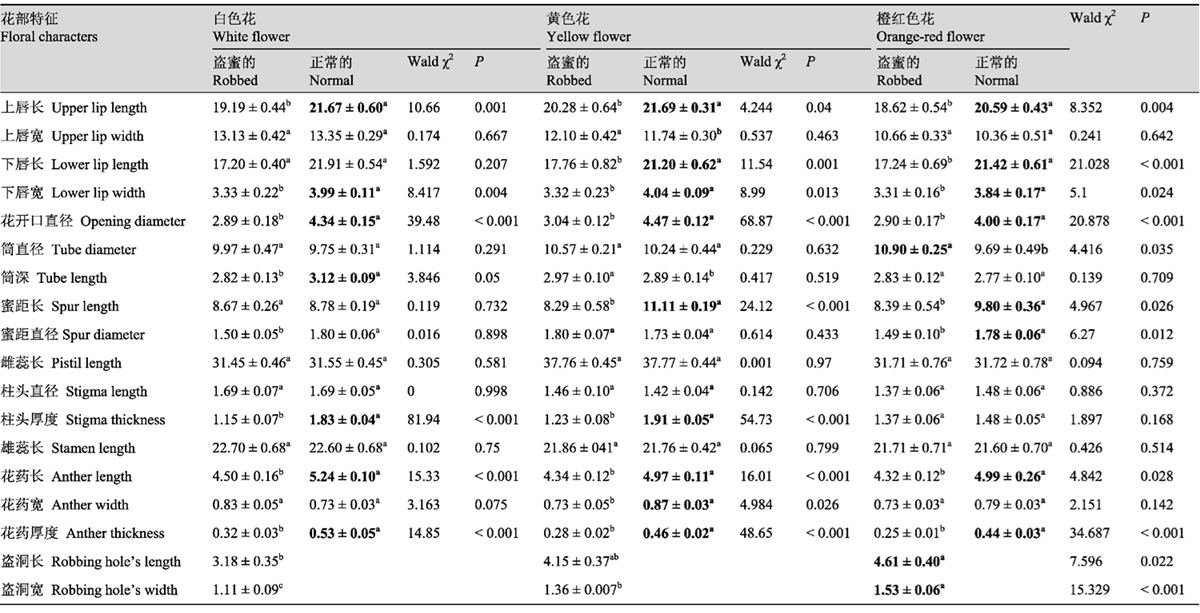

Table 2 Comparison of floral characters between robbed and normal unrobbed flowers (white, yellow and orange-red) of Lonicera calcarata and nectar robbing hole size among these three colors flowers (mean土SE, units: mm, generalized linear model analysis). Different lowercase letters in the same row for one color flower indicate significant difference in the floral characters between robbed and normal flowers, with larger value in bold.

|

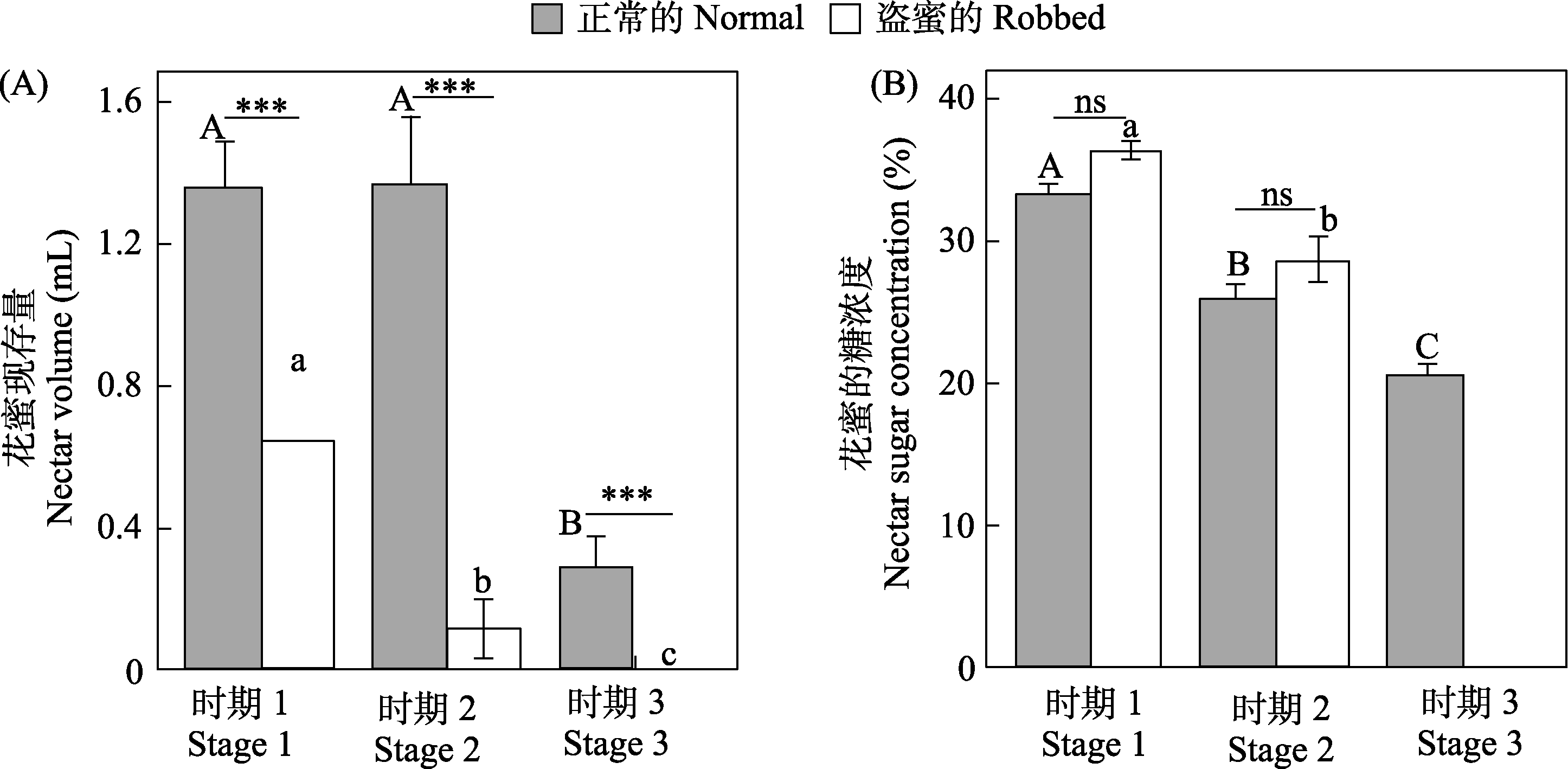

Fig. 3 Comparison of nectar volume (A) and sugar concentration (B) during three flowering stages of normal and robbed Lonicera calcarata flowers. Different uppercase letters indicate significant difference in nectar volume or sugar concentration of normal L. calcarata flowers at different stages. Different lowercase letters indicate significant difference in nectar volume or sugar concentration of robbed L. calcarata at different stages. *** indicates a significant difference (P < 0.001) between two treatments at the same stage, and “ns” indicates no significant difference (P > 0.05) between two treatments at the same stage.

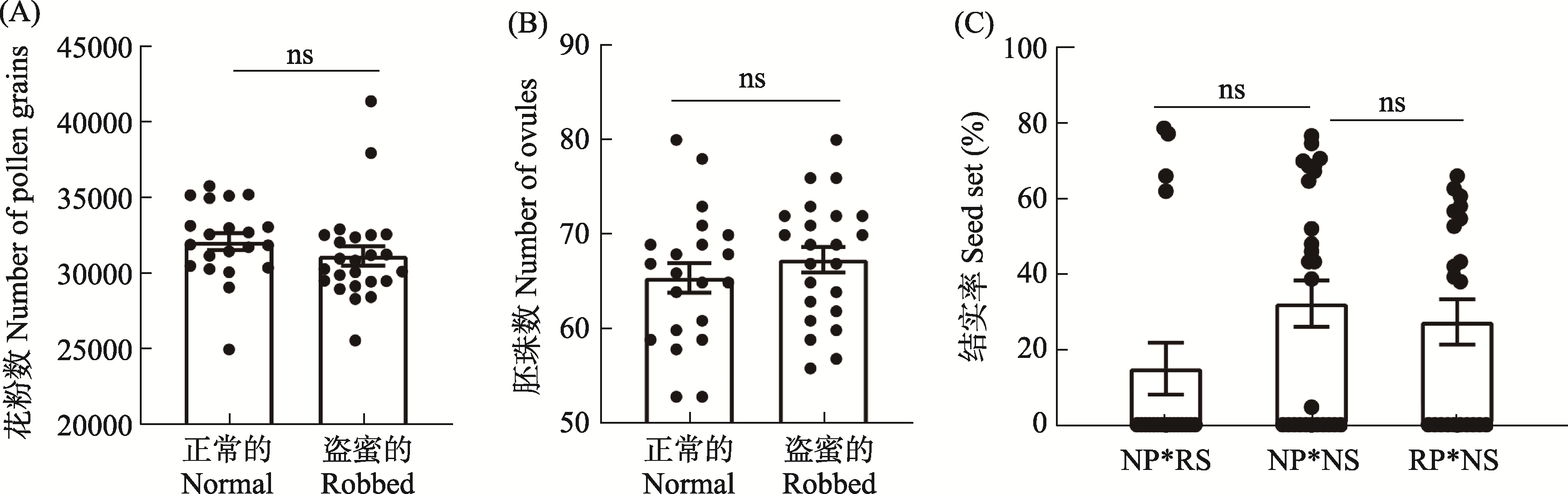

Fig. 4 Comparison of total number of pollen grains (A) and ovules (B) between normal and robbed flower buds of Lonicera calcarata, and comparison of seed sets among different pollination treatments (C). Normal pollen * robbed stigma, abbreviated to NP*RS; normal pollen*normal stigma, abbreviated to NP*NS; robbed pollen * normal stigma, abbreviated to RP*NS. “ns” indicates no significant difference between the different treatments (P > 0.05).

| [1] | Carrió E, Güemes J (2019) Nectar robbing does not affect female reproductive success of an endangered Antirrhinum species, Plantaginaceae. Plant Ecology & Diversity, 12, 159-168. |

| [2] | de Souza CV, Salvador MV, Tunes P, Di Stasi LC, Guimarães E (2019) I’ve been robbed! Can changes in floral traits discourage bee pollination? PLoS ONE, 14, e0225252. |

| [3] | Deng H, Xiang GJ, Guo YH, Yang CF (2017) Study on the breeding system and floral color change of four Lonicera species in the Qinling Mountains. Plant Science Journal, 35, 1-12. (in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [邓惠, 向甘驹, 郭友好, 杨春锋 (2017) 秦岭忍冬属4种植物的繁育系统及花色变化的研究. 植物科学学报, 35, 1-12.] | |

| [4] | Eidesen PB, Little L, Müller E, Dickinson KJM, Lord JM (2017) Plant-pollinator interactions affect colonization efficiency: Abundance of blue-purple flowers is correlated with species richness of bumblebees in the Arctic. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 121, 150-162. |

| [5] | Feng HH, Wang XY, Luo YB, Huang SQ (2023) Floral scent emission is the highest at the second night of anthesis in Lonicera japonica(Caprifoliaceae). Journal of Systematics and Evolution, 61, 530-537. |

| [6] | Hazlehurst JA, Karubian JO (2016) Nectar robbing impacts pollinator behavior but not plant reproduction. Oikos, 125, 1668-1676. |

| [7] | Heiling JM, Ledbetter TA, Richman SK, Ellison HK, Bronstein JL, Irwin RE (2018) Why are some plant-nectar robber interactions commensalisms? Oikos, 127, 1679-1689. |

| [8] | Hou QZ, Ehmet N, Chen DW, Wang TH, Xu YF, Ma J, Sun K (2021) Corolla abscission triggered by nectar robbers positively affects reproduction by enhancing self-pollination in Symphytum officinale(Boraginaceae). Biology, 10, 903. |

| [9] | Inouye DW (1983) The ecology of nectar robbing. In: The Biology of Nectaries (eds Bentley B, Elias T), pp. 153-173. Columbia University Press, New York. |

| [10] | Irwin RE, Brody AK (1999) Nectar-robbing bumble bees reduce the fitness of Ipomopsis aggregata(Polemoniaceae). Ecology, 80, 1703-1712. |

| [11] | Irwin RE, Bronstein JL, Manson JS, Richardson L (2010) Nectar robbing: Ecological and evolutionary perspectives. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 41, 271-292. |

| [12] | Irwin RE, Howell P, Galen C (2015) Quantifying direct vs. indirect effects of nectar robbers on male and female components of plant fitness. Journal of Ecology, 103, 1487-1497. |

| [13] |

Irwin RE, Maloof JE (2002) Variation in nectar robbing over time, space, and species. Oecologia, 133, 525-533.

DOI PMID |

| [14] | Li JJ, Lian XY, Ye CL, Wang L (2019) Analysis of flower color variations at different developmental stages in two honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.)cultivars. HortScience, 54, 779-782. |

| [15] | Mackin CR, Goulson D, Castellanos MC (2021) Novel nectar robbing negatively affects reproduction in Digitalis purpurea. Ecology and Evolution, 11, 13455-13463. |

| [16] | Maidana-Tuco YN, Larrea-Alcázar DM, Pacheco LF (2024) Nectar robbing effects on pollinators of a key nectar source plant (Tecoma fulva, Bignoniaceae) in a dry tropical Andean valley. Biotropica, 56, e13319. |

| [17] | Makino TT, Ohashi K (2017) Honest signals to maintain a long-lasting relationship: Floral colour change prevents plant-level avoidance by experienced pollinators. Functional Ecology, 31, 831-837. |

| [18] |

Maloof JE (2001) The effects of a bumble bee nectar robber on plant reproductive success and pollinator behavior. American Journal of Botany, 88, 1960-1965.

PMID |

| [19] | Ohashi K, Makino TT, Arikawa K (2015) Floral colour change in the eyes of pollinators: Testing possible constraints and correlated evolution. Functional Ecology, 29, 1144-1155. |

| [20] | Raine NE, Chittka L (2007) Flower constancy and memory dynamics in bumblebees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus). Entomologia Generalis, 29, 179-199. |

| [21] | Richman SK, Barker JL, Baek M, Papaj DR, Irwin RE, Bronstein JL (2021) The sensory and cognitive ecology of nectar robbing. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 698137. |

| [22] |

Rojas-Nossa SV, Sánchez JM, Navarro L (2016) Effects of nectar robbing on male and female reproductive success of a pollinator-dependent plant. Annals of Botany, 117, 291-297.

DOI PMID |

| [23] |

Rojas-Nossa SV, Sánchez JM, Navarro L (2021) Nectar robbing and plant reproduction: An interplay of positive and negative effects. Oikos, 130, 601-608.

DOI |

| [24] | Sun SG, Liao K, Xia J, Guo YH (2005) Floral colour change in Pedicularis monbeigiana(Orobanchaceae). Plant Systematics and Evolution, 255, 77-85. |

| [25] |

Tie S, He YD, Lázaro A, Inouye DW, Guo YH, Yang CF (2023) Floral trait variation across individual plants within a population enhances defense capability to nectar robbing. Plant Diversity, 45, 315-325.

DOI |

| [26] | Traveset A, Willson MF, Sabag C (1998) Effect of nectar-robbing birds on fruit set of Fuchsia magellanica in Tierra Del Fuego: A disrupted mutualism. Functional Ecology, 12, 459-464. |

| [27] | Varma S, Rajesh TP, Manoj K, Asha G, Jobiraj T, Sinu PA (2020) Nectar robbers deter legitimate pollinators by mutilating flowers. Oikos, 129, 868-878. |

| [28] | Wang XY, Yao RX, Lv XQ, Yi Y, Tang XX (2023) Nectar robbing by bees affects the reproductive fitness of the distylous plant Tirpitzia sinensis(Linaceae). Ecology and Evolution, 13, e10714. |

| [29] | Weiss MR (1991) Floral colour changes as cues for pollinators. Nature, 354, 227-229. |

| [30] | Weiss MR, Lamont BB (1997) Floral color change and insect pollination: A dynamic relationship. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, 45, 185-199. |

| [31] | Willmer P (2011) Pollination and Floral Ecology. Princeton University Press, Princeton. |

| [32] | Yang QE, Sven L, Joanna O, Renata B (2011) Lonicera. In: Flora of China, Vol. 19 (eds Wu ZY, Raven PH, Hong DY), pp. 620-641. Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis. |

| [33] | Ye ZM, Jin XF, Wang QF, Yang CF, Inouye DW (2017) Nectar replenishment maintains the neutral effects of nectar robbing on female reproductive success of Salvia przewalskii (Lamiaceae), a plant pollinated and robbed by bumble bees. Annals of Botany, 119, 1053-1059. |

| [34] | Zhang YW, Wang Y, Guo YH (2006) The effects of nectar robbing on plant reproduction and evolution. Journal of Plant Ecology (Chinese Version), 30, 695-702. (in Chinese with English abstract) |

|

[张彦文, 王勇, 郭友好 (2006) 盗蜜行为在植物繁殖生态学中的意义. 植物生态学报, 30, 695-702.]

DOI |

|

| [35] | Zhu XF, Wan JP, Li QJ (2010) Nectar robbers pollinate flowers with sexual organs hidden within corollas in distylous Primula secundiflora (Primulaceae). Biology Letters, 6, 785-787. |

| [36] | Zimmerman M, Cook S (1985) Pollinator foraging, experimental nectar-robbing and plant fitness in Impatiens capensis. American Midland Naturalist, 113, 84. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||

Copyright © 2022 Biodiversity Science

Editorial Office of Biodiversity Science, 20 Nanxincun, Xiangshan, Beijing 100093, China

Tel: 010-62836137, 62836665 E-mail: biodiversity@ibcas.ac.cn ![]()