两性花与单性花在不同空间和时间上的组合, 形成了被子植物性系统的多样性(Barrett, 2002; Yakimowski & Barrett, 2014)。植物性系统可归结为雌雄异株和雌雄同株两种类型: 前者包括雌花雄花异株、雌全异株、雄全异株和雄花雌花两性花异株; 后者包括雌雄异花同株、雌雄同花(种群内只有两性花植株)、雌全同株、雄全同株和雌花雄花两性花同株(Ainsworth, 2000)。目前, 进化生物学家的共识是开花植物进化出复杂多样的性器官是为了实现繁殖功能(Barrett, 2002)。植物性系统特征作为植物繁殖策略的体现, 是研究植物进化适应问题的关键, 因而其多样性一直是进化生物学和植物生态学领域重要的研究主题之一(Weller, 2009; Barrett, 2010)。

大多数被子植物开两性花, 然而由于两性花中雌雄器官是集中在同一朵花内, 虽然增加了自交授粉机会, 但同时也带来了雌雄功能相互干扰的问题, 为避免这种干扰以及实现资源优化配置, 部分开花植物的性器官由联合走向分离(Webb & Lloyd, 1986; Barrett, 2002)。性表达方面的灵活性是对遗传或生态限制的一种适应, 这种灵活性一方面可能是遗传因素的影响, 另一方面可能是植物面对异质环境的表型可塑性(Ashman, 2006; Renner, 2014; Sabatti et al, 2020)。环境条件可能通过影响植物可利用资源状况、繁殖物候、种群分布格局以及传粉者种群动态等方面来改变植物性别表达策略(Devaux et al, 2014; 袁川等, 2021)。植物种群内个体的空间分布模式反映了该物种生长与繁殖过程中经历的多种生态学适应过程, 有利于阐明植物群落的稳定性与演替规律、生态系统的形成与维持机制(Nathan & Muller-Landau, 2000; 倪瑞强等, 2013)。特别是研究植物种群中不同性别表型个体的空间分布对于保护野生植物和认识生物多样性维持机制具有重要意义。根据资源分配的基本原则, 每个个体拥有的资源是有限的, 增加对某一功能的投入就要以减弱其他功能为代价, 即植物生长发育过程中各功能间的资源分配存在着动态的权衡, 植物通过分配、控制不同构件生长来响应环境状况的变化(Charnov, 1982; Elle, 1999)。其中, 多年生植物面临着当下生长繁殖与将来生长繁殖之间的权衡, 由于雌性个体既要生产胚珠又要生产果实, 导致实现雌性功能的资源成本远高于实现雄性功能(Charnov, 1982), 植物性表达的大小依赖假说认为大的个体具有较多的资源, 能够负担成本较高的雌性功能而开雌花或者两性花, 而小的个体倾向于只开低成本的雄花甚至不开花(Lloyd & Bawa, 1984; Zhang & Jiang, 2002; Kawagoe & Suzuki, 2005; Guo et al, 2010)。该假说也认为有些植物种群中个体小的开花植株能通过选择雌性败育, 只保留雄蕊而发挥雄性功能的方式, 来适应有限资源或极端环境从而实现资源最优分配(Schlessman, 1991), 这进一步增加了植物性表达的复杂性(Lloyd & Bawa, 1984)。大小依赖的性表达现象在百合科贝母属(Fritillaria) (Peruzzi et al, 2012)、天南星属(Arisaema) (Policansky, 1981; Bierzychudek, 1984)以及五加科人参属(Panax) (Schlessman, 1987)的部分物种中有报道。多年生开花植物在有性繁殖过程中的个体性表达在年份之间产生变化(转换)的现象, 则称为性二相(gender diphasy)的性系统, 这种现象被认为是大小依赖的性表达结果(Zhang et al, 2014)。性二相本质上应该属于雌雄同株, 植物个体在年度之间的性别表达差异, 导致了在其种群中同一年份里具有不同性别表型的个体存在, 造成这类植物在种群水平上更为灵活的性表达变化模式。通常性二相植物个体在单一年度仅具有一种性别功能的花朵, 而如果性二相植物出现同一植株上同时出现雄花和两性花的现象, 这将比雄全异株的植物在进化适应上更为复杂, 这种性系统的适应过程可能受多方面因素的影响。

开花植物的花粉限制、近交衰退等生物因素的作用对其性系统特征进化产生选择压力, 植物性分离现象曾被认为是远交优势选择的结果。但近年来通过评估雌雄功能适合度, 研究者们趋向于将其解释为调节两性资源配置模式以提高两性的进化适合度(黄双全和郭友好, 2000)。理论上, 两性植株被认为雌雄功能相当, 在具有雌性不育系统的物种中, 其雄性个体至少比两性个体要多出2倍的雄性适合度才能弥补其由于雌性败育而在遗传上损失的竞争力(Pannell, 2002a, b; Peruzzi et al, 2012)。雄性植株可以通过产生比两性植株更多的花粉、提高花粉活力、增加花朵吸引力或访花报酬等来促进繁殖目标的完成(Liston et al, 1990; Philbrick & Rieseberg, 1994; Ishida & Hiura, 1998; Muenchow, 1998)。例如雄全异株植物木犀科的Phillyrea angustifolia在人工授雄花花粉处理下比授两性花花粉产生更多的果实, 雄花的雄性功能高于两性花(Vassiliadis et al, 2000)。然而对雄全异株的波斯贝母(Fritillaria persica)进行花粉数量、萌发实验和杂交检验, 结果显示其雄花植株和两性花植株的雄性适合度无显著差异(Mancuso & Peruzzi, 2010)。此外, 一些植物虽具有雄全异株的表型, 但功能上为雌雄异株, 两性个体的雄性结构无功能或不能使胚珠受精, 被称为隐性雌雄异株(cryptic dioecy) (Mayer & Charlesworth, 1991)。雄全同株植物粉色西番莲(Passiflora incarnata)的人工授雄花花粉种子产量是两性花花粉的2倍, 雄花的雄性功能高于两性花(Dai & Galloway, 2012), 而新疆郁金香(Tulipa sinkiangensis)、刺山柑(Capparis spinosa)的雄花在单花花粉量、花粉败育率、雄性功能等方面与两性花却没有显著差异(张涛和谭敦炎, 2008; 王娟等, 2018)。

性系统多样性的进化对植物的交配策略有一定的影响, 植物从而表现出从完全自交到专性异交, 以及混合的多样化交配策略, 由此影响植物的后代(种子)的适合度(张振春和谭敦炎, 2012)。研究较多的是近交衰退, 如近交衰退可以导致黄瓶子草(Sarracenia flava)种子数量、质量下降, 自交种子产生的后代在萌发、出苗和生长等阶段都不如异交产生的种子后代(Sheridan & Karowe, 2000); 而在Lupinus arboreus中近交衰退表现为结实率有差别, 而萌发、出苗和生长等阶段等没有明显差别(Kittelson & Maron, 2000)。现有研究多集中于性系统进化对植物雄性功能适合度的影响, 缺乏进一步探讨其对后代适合度的影响。

开花植物性器官由联合走向分离并不常见, 据统计, 仅有少数被子植物性系统出现该现象, 经实验证实的植物类群更是少数(Schlessman, 1987)。通过雄性败育雌花植株成功入侵到两性花种群的物种大约占被子植物总数的7%‒10%, 而雌性败育雄花植株成功入侵到两性花种群的物种大约仅占被子植物的1%‒2% (Vallejo-Marín & Rausher, 2007; Peruzzi et al, 2012; 龚强帮等, 2015)。百合科植物中发生雌性败育的频率远高于发生雄性败育的频率, 百合科植物种群中雄花植株盛行的现象已经引起了学者们的关注(龚强帮等, 2015)。目前, 在百合科中已经在贝母属(Mancuso & Peruzzi, 2010)、白丝草属(Chiongraphis) (Maki, 1993)、洼瓣花属(Lloydia) (Jones & Gliddon, 1999; Manicacci & Després, 2001)、大百合属(Cardiocrinum) (Cao & Kudo, 2008)、顶冰花属(Gagea) (Peruzzi et al, 2008)、郁金香属(Tulipa) (Niu et al, 2017)和百合属(Lilium) (Zhang et al, 2014)等类群的植物中报道过有雄花植株出现。

大花百合(Lilium concolor var. megalanthum)作为长白山区唯一生长于泥炭沼泽湿地的百合属物种, 野生种群数量正逐年下降, 历史上调查曾经有生长记录的地点90%现已无野生种群(崔凯峰等, 2018)。由于种群数量稀少, 分布范围较窄, 对其种群生态学方面的研究很少。根据文献查阅, 现有对大花百合的研究仅仅涉及资源调查(周繇, 2006)、引种驯化(于长宝等, 2019)和核型遗传多样性(荣立苹等, 2009)等方面, 对其野外种群的分布状况以及性系统特征没有进行过详细研究。我们在前期的野外考察过程中, 发现大花百合种群中存在柱头退化的个体。基于以上原因, 本研究调查了吉林省金川泥炭沼泽湿地中大花百合的表型性别(个体和种群水平)及野外种群分布情况, 并通过比较雄花植株和两性花植株的表型差异, 验证其性表达是否依赖于个体大小; 通过比较两种花型花粉可育性和来源不同的花粉授粉处理结实后的种子活力, 探讨大花百合性系统的进化意义。结果可为深入了解百合属的性系统进化及大花百合种群的繁衍复壮与保护提供参考。

1 材料与方法

1.1 研究地点概况

研究地点位于吉林省通化市境内龙湾国家级自然保护区内有大花百合自然种群分布的湿地——金川泥炭沼泽, 其地理坐标为42°20′56″ N, 126°22′51″ E, 海拔613-619 m, 总面积约9,860 ha, 该泥炭沼泽湿地草本层优势种为瘤囊薹草(Carex schmidtii)和细花薹草(C. tenuiflora)。研究地受温带大陆性季风气候影响, 年均温4.1℃, 年均降水量704.2 mm, 且多集中于7、8月份, 无霜期134 d左右, 年均蒸发量1,276.1 mm, 年均相对湿度70%, 以大气降水为主要水源补给方式(施瑶, 2019)。

1.2 研究材料

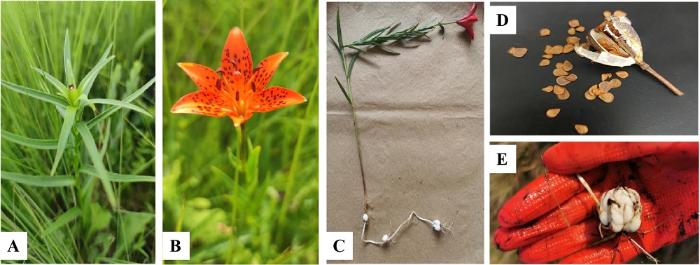

图1

图1

大花百合植株形态特征。A: 未开花; B: 开花; C: 全株; D: 果实和种子; E: 鳞茎。

Fig. 1

Morphological characteristics of Lilium concolor var. megalanthum. A, No-flowering plant; B, Flowering plant; C, The whole plant; D, Fruits and seeds; E, Bulb.

1.3 研究方法

1.3.1 大花百合种群中植株性别表达和分布格局

于2012年7月17日和2020年7月14‒15日(盛花期)在研究地根据大花百合的实际分布情况分别选择3个种群进行样地设置, 相邻样地之间距离30-100 m不等。其中, 2012年的3块样地规格分别为82.5 m × 35 m、82.5 m × 56.3 m、86.1 m × 45 m; 2020年的3块样地规格均为80 m × 50 m。首先调查大花百合主要分布的生境以及伴生的植物种类, 并对样地中大花百合所有植株的性别类型(雄花植株与两性花植株)进行统计与标记, 2020年的调查中增加记录植株坐标。在进行植株花性别类型记录时, 由于大花百合绝大多数为单花植株, 调查中罕见开双花和三花 及以上的植株, 我们仅统计单花植株。其中, 兼具雄蕊和雌蕊(具正常柱头和子房)的花和无花有果的记作两性花植株; 只具有雄蕊或柱头退化的记作雄花植株; 花内花蕊残缺不全无法辨别的、未开放的花苞不作记录。为了量化种群水平的表型性别, 用Lloyd (1980)提出的表型性别的计算公式Gi = oi /(oi + piE), E = ∑oi /∑pi量化大花百合种群水平的性别分布。式中, oi是植株i的雌性投入, 这里我们用提供胚珠的花(两性花)数量来衡量, pi是植株i的雄性投入, 用提供花粉的花(两性花和雄花)数量来衡量, E是种群中所有个体对雌性和雄性功能投入的比值。Gi的范围为0 (只产生花粉的植株)‒1 (只产生胚珠的植株), Gi值越大表明其表型性别越偏雌性。

1.3.2 两种主要性别表型植株的生长特征及生物量分配

为了明确大花百合具两性花和雄花这两种性别表型植株的形态特征差异, 在盛花期随机选取开花植株(30株两性花植株和30株雄花植株)测量以下形态指标: 株高(植株地表以上高度)、基径(地面茎直径)、叶片数、叶长、叶宽、花瓣长(沿中脉从基部到顶点的距离)、花瓣宽(与中脉垂直方向的最宽处)、花直径(一侧花瓣尖端通过中心至相对一侧花瓣尖端的距离)、雄蕊长(从花丝底部到花药顶端)、柱头高度(从子房上部到柱头顶部)、子房高度(从花柱基部到子房顶部)。然后完整挖取植株, 编号带回实验室。将植株样品的泥土洗净并去除杂草后, 将其分为根、鳞茎、茎、叶、花5部分, 标记后分别装入信封, 置于105℃烘箱0.5 h后, 再80℃烘干至恒重, 使用万分之一天平称重, 并记录结果。计算如下指标:

地上生物量 = 花干重 + 茎干重 + 叶干重;

地下生物量 = 地下茎干重 + 鳞茎干重 + 须根干重;

总生物量 = 地上生物量 + 地下生物量;

花分配 = 花干重/总生物量; 茎分配 = 茎干重/总生物量; 叶分配 = 叶干重/总生物量; 地下茎分配 = 地下茎干重/总生物量; 鳞茎分配 = 鳞茎干重/总生物量; 须根分配 = 须根干重/总生物量; 地上生物量分配 = 地上生物量/总生物量; 地下生物量分配 = 地下生物量/总生物量。

1.3.3 两种主要性别表型植株雄性功能比较

设置4种授粉处理, 分别为自然授粉、人工自花授粉、人工异花授雄花植株的花粉和人工异花授两性花植株的花粉。其中, 自然授粉不作任何处理, 用以检测自然状态下的结籽情况; 人工授粉处理需在开花前, 对饱满程度基本相似的单花植株的花苞进行套袋、标记, 并对授异株花粉的植株进行去雄处理, 在开花当天分别授以同株花粉、异株花粉(分两类花粉: 雄花植株花粉和两性花植株花粉)后套袋。授粉操作于2020年7月盛花期进行。人工授粉在开花当天8:00‒12:00进行, 各处理样本中的单花重复授粉两次, 间隔1 h以保证花粉均匀饱和。野外研究过程中, 采用透气透光的白色网袋对开花前和授粉后的花朵进行套袋处理, 以避免昆虫活动的影响。9月中旬蒴果开裂时进行采收, 并收集种子, 统计比较其果荚长、果荚宽、坐果率(坐果率 = 坐果数/处理单花数)、结籽率(结籽率 = 饱满结籽数/总胚珠数)、种子数量、种子千粒重。以上每种处理均选取大花百合至少20株。

将上述不同授粉处理得到的大花百合种子作表面消毒后用去离子水清洗3遍, 然后将种子平放在灭菌且带有滤纸的培养皿中, 注入去离子水使滤纸保持湿润状态。将培养皿置于25℃的人工气候箱, 比较不同授粉处理得到的种子萌发特性差异。萌发光照周期设置为12 h光(6:00-18:00)/12 h暗, 光照强度为5,500 lx。每个培养皿放置30粒种子(相同授粉处理的种子混合)作为1个重复, 每种来源种子的处理共设置4个重复。逐日统计培养皿中萌发的种子数, 记录后及时取出已萌发的种子, 观察记录至所有处理连续15天均无种子萌发, 停止观察。统计以下萌发参数:

初始萌发时间 = 从实验开始到第1粒种子萌发所需的时间(d);

萌发率(%) = 萌发种子数/供试种子数 × 100%;

萌发势(%) = 日萌发种子数最大时的萌发种子数/供试种子数 × 100%;

萌发指数 = ∑(Gt / Dt), 式中Gt为日萌发数, Dt为萌发天数。

1.4 数据分析

式中, K(r)为Ripley's K函数, r为尺度, A为样地面积, n为个体总数。uij为i和j两点之间的距离, 当i和j的距离u ≤ r时, Ir(u)为l, 反之则为0; Wij为权重值, 用于边缘校正。点格局分析通过Monte Carlo随机模拟99%的置信区间并分别利用模拟的最大值和最小值生成上下两条包迹线。g(r) = 1对应完全随机分布, g(r) > 1为聚集分布, g(r) < 1为均匀分布。点格局分析用R 3.6.1版本中的spatstat程序包进行数据处理。

其他实验数据均用SPSS 20.0、Canoco 5统计分析软件进行分析, 使用Origin 9.2软件绘图。通过主成分分析进行生长特征降维排序及对象分类, 使用独立样本t检验、One-way ANOVA分析和Duncan多重比较检验(数据符合正态分布、方差齐性)或非参数检验中的秩和检验和Kruskal-Wallis方法(数据转换后仍不符合正态分布、方差齐性)检验相关变量间是否存在显著性差异。对大花百合两种性别表型植株花分配与总生物量进行Pearson相关分析, 并在相关的基础上对二者进行线性回归分析。显著性检验的显著度设为0.05 (α = 0.05), 统计数据用平均值 ± 标准误表示。

2 结果

2.1 大花百合性别表达和分布格局

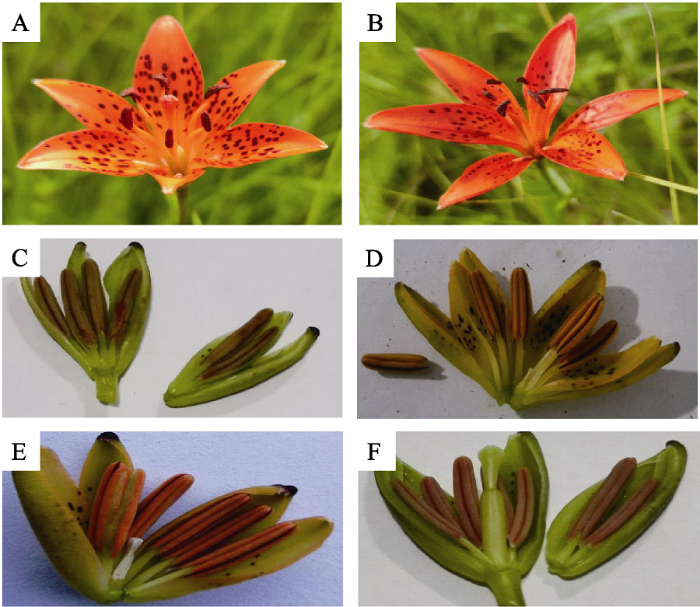

金川泥炭沼泽湿地中大花百合主要分布于湿地边缘处, 少量分布于湿地中心区域绣线菊(Spiraea salicifolia)丛, 个别零散分布于芦苇(Phragmites communis)群落和蓝靛果忍冬(Lonicera caerulea)灌木区。大花百合伴生种有薹草(Carex spp.)、黄莲花(Lysimachia davurica)、千屈菜(Lythrum salicaria)、十字兰(Habenaria schindleri)、老鹳草(Geranium wilfordii)、紫花鸢尾(Iris ensata)、败酱(Patrinia scabiosaefolia)、绣线菊。金川泥炭沼泽湿地大花百合多数植株开单花, 极少数较大的植株开双花, 开三花以上极为罕见。野外调查发现大花百合存在不同程度的柱头退化现象, 其正常的雌蕊与雄蕊等高, 但退化的雌蕊则显著低于雄蕊或完全消失(图2)。在金川泥炭沼泽大花百合的自然种群中, 共记录到3种性表达个体类型, 即两性花个体、雄性花个体和极少数雄花两性花同株个体。由于调查过程中仅发现1株存在雄花两性花同株现象的个体, 以下分析仅对两性花和雄花个体作统计。

图2

图2

大花百合自然种群中两种不同表型的花形态特征。A:两性花; B: 雄花; C‒E: 退化的雌蕊; F: 正常雌蕊。

Fig. 2

Flower morphological characteristics of two different phenotypes in natural population of Lilium concolor var. megalanthum. A, Hermaphroditic flower; B, Male flower; C‒E, Rudimentary pistil during flowering; F, Normally well-developed pistil.

2012年3块样地分别统计了664 (561:103, 两性花植株:雄花植株, 下同)、335 (277:58)、531 (445:86)株, 共计1,530株; 2020年3块样地分别统计了242 (147:95)、300 (201:99)、124 (68:56)株, 共计666株。结果显示, 个体水平上, 在2020年大花百合种群中两性花植株数量所占比例为60.86%, 雄花植株所占比例为39.14%, 种群中两性花与雄花植株比例接近3:2, 与2012年两性花植株数量比例(83.66%) (t = -6.423, df = 4, P < 0.01)和雄花植株比例(16.34%) (t = 6.423, df = 4, P < 0.01)有显著差异(表1)。与2012年相比, 2020年雄花植株出现频率显著升高, 增加了22.80%。此外, 大花百合种群的密度下降明显, 调查显示2020年种群密度为0.06株/m2, 较2012年下降了0.09株/m2; 其中两性花植株密度下降了0.09株/m2, 雄花植株密度变化不明显(表1)。种群水平上, 2020年较2012年纯雄性比例增加, 偏雌性比例下降但Gi值上升, 年际间均未出现纯雌性的性别表达(图3)。

表1 大花百合两种性别表型植株比例和分布密度的年际变化(平均值 ± 标准误)

Table 1

| 年份 Year | 植株比例 Percentage of plant (%) | 密度 Density (plants/m2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 两性花植株 Hermaphrodite | 雄花植株 Male | 总计 Total | 两性花植株 Hermaphrodite | 雄花植株 Male | 总计 Total | ||

| 2012 (N = 1,530) | 83.66 ± 0.53a | 16.34 ± 0.53a | 100 | 0.13 ± 0.04a | 0.02 ± 0.01a | 0.15 ± 0.05a | |

| 2020 (N = 666) | 60.86 ± 3.51b | 39.14 ± 3.51b | 100 | 0.04 ± 0.01a | 0.02 ± 0.00a | 0.06 ± 0.01a | |

同列不同字母表明差异显著(P < 0.05)

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05)

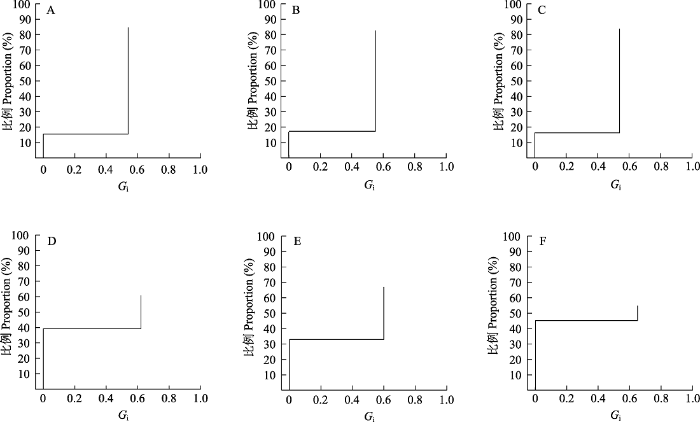

图3

图3

大花百合种群的表型性别分布。A‒C: 2012年调查的3个种群; D‒F: 2020年调查的3个种群。

Fig. 3

The distribution of phenotypic gender in the populations of Lilium concolor var. megalanthum. A‒C, The three populations surveyed in 2012; D‒F, The three populations surveyed in 2020.

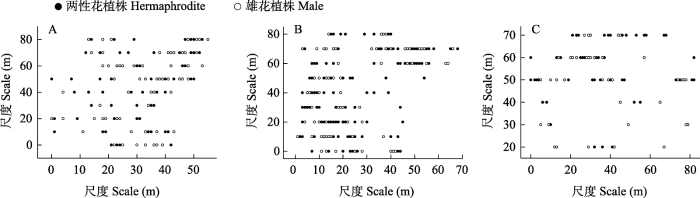

图4

图4

2020年大花百合不同性别表型植株在样地中的空间分布。A:样地1; B: 样地2; C: 样地3。

Fig. 4

Spatial distribution of individuals of different sexual phenotypes of Lilium concolor var. megalanthum in sample plots in 2020. A, Plot 1; B, Plot 2; C, Plot 3.

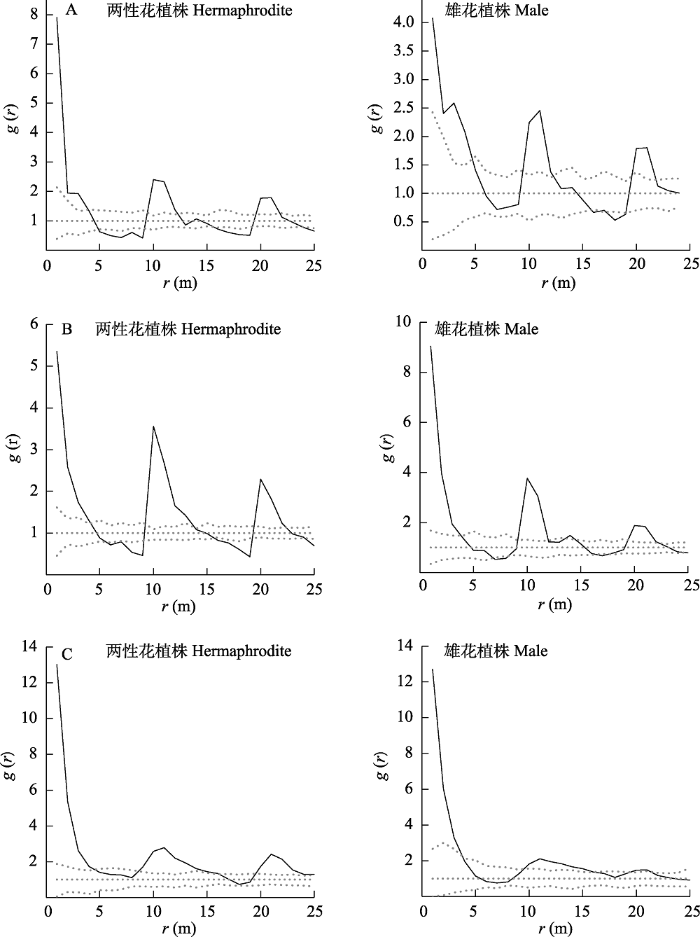

图5

图5

2020年大花百合两种性别表型植株的空间分布格局。A:样地1; B: 样地2; C: 样地3。

Fig. 5

Spatial distribution pattern of two sexual phenotypes of Lilium concolor var. megalanthum in 2020. A, Plot 1; B, Plot 2; C, Plot 3.

2.2 不同性别表型植株的形态及生物量分配差异

大花百合雄花植株与两性花植株形态大小有显著差异(表2)。雄花植株的株高(Z = -3.394, df = 58, P < 0.01)、叶片数(t = 7.070, df = 58, P < 0.001)、基径(Z = -3.950, df = 58, P < 0.001)、花直径(t = 4.300, df = 58, P < 0.001)、花瓣长(t = -5.430, df = 58, P < 0.001)、花瓣宽(Z = -5.132, df = 58, P < 0.001)、雄蕊长(Z = -3.555, df = 58, P < 0.001)等指标均显著小于两性花植株, 而两种性别表型个体在叶长(Z = -0.364, df = 58, P > 0.05)、叶宽(Z = -0.367, df = 58, P > 0.05)两项指标上差异不显著。

表2 大花百合两种性别表型植株的形态特征比较(平均值 ± 标准误)

Table 2

| 指标 Parameters | 两性花植株 Hermaphrodite (N = 30) | 雄花植株 Male (N = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| 株高 Plant height (cm) | 49.35 ± 1.15a | 44.45 ± 0.88b |

| 叶片数 Leaf number | 17.17 ± 0.44a | 12.77 ± 0.44b |

| 叶长 Leaf length (cm) | 6.70 ± 0.17a | 6.53 ± 0.12a |

| 叶宽 Leaf width (cm) | 0.73 ± 0.03a | 0.70 ± 0.02a |

| 基径 Base diameter (cm) | 0.23 ± 0.01a | 0.19 ± 0.01b |

| 花直径 Flower diameter (cm) | 5.64 ± 0.18a | 4.65 ± 0.15b |

| 花瓣长 Corolla length (cm) | 4.23 ± 0.10a | 3.52 ± 0.07b |

| 花瓣宽 Corolla width (cm) | 1.51 ± 0.04a | 1.18 ± 0.03b |

| 雄蕊长 Stamen length (cm) | 2.68 ± 0.04a | 2.47 ± 0.05b |

同行不同字母表明差异显著(P < 0.05)

Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

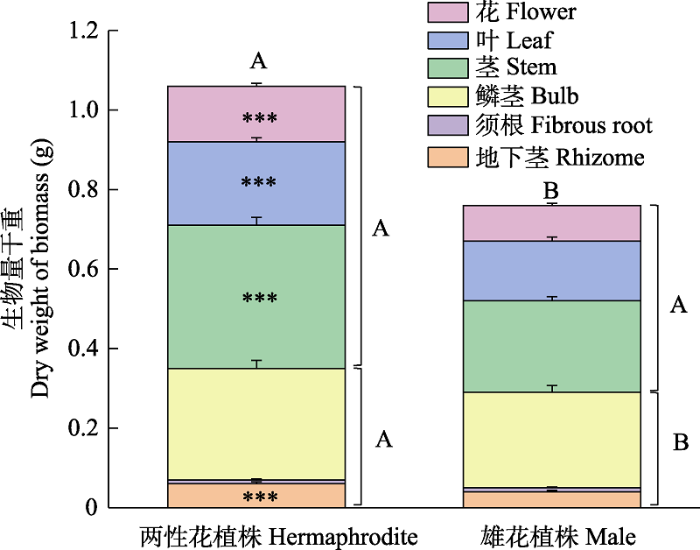

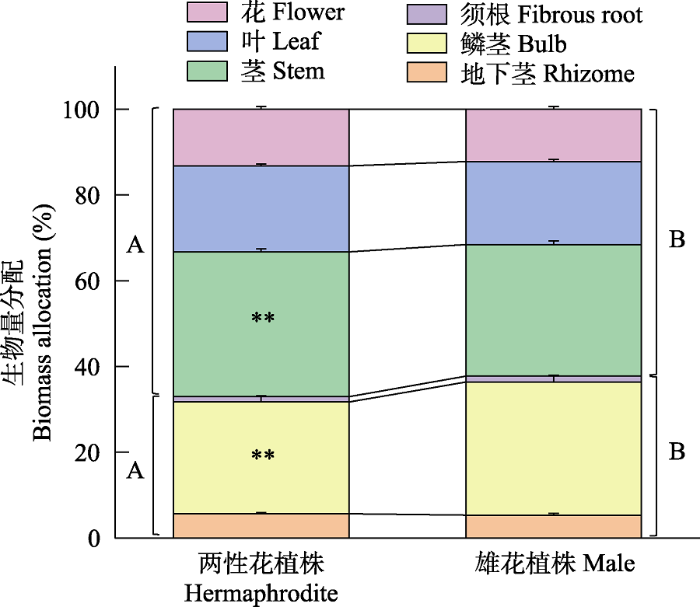

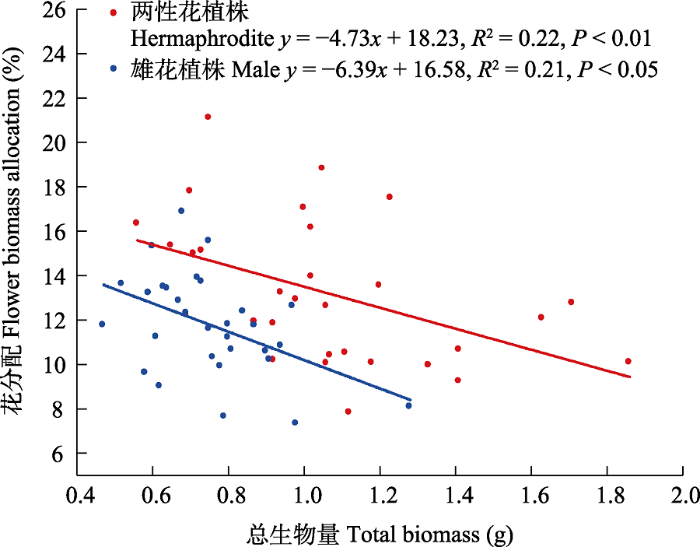

大花百合雄花植株的茎干重(t = 6.021, df = 58, P < 0.001)、叶干重(t = 4.949, df = 58, P < 0.001)、花干重(t = 5.842, df = 58, P < 0.001)、地下茎干重(t = 3.689, df = 58, P < 0.001)、地上生物量(t = 6.285, df = 58, P < 0.001)、总生物量(t = 4.872, df = 58, P <0.001)、茎分配(t = 2.785, df = 58, P < 0.01)、地上生物量分配(t = -2.774, df = 58, P < 0.01)均显著低于两性花植株; 而雄花植株的鳞茎分配(t = -2.705, df = 58, P < 0.01)和地下生物量分配(t = 2.774, df = 58, P < 0.01)显著高于两性花植株, 反映了雄花植株会把更多资源投入到鳞茎进行无性繁殖; 其他指标如鳞茎干重(t = 1.636, df = 58, P > 0.05)、须根干重(t = 0.265, df = 58, P > 0.05)、地下生物量(t = 1.976, df = 58, P > 0.05)、花分配 (t = 1.881, df = 58, P > 0.05)、叶分配(Z = -0.636, df = 58, P > 0.05)、地下茎分配(t = 0.632, df = 58, P > 0.05)和须根分配(t = -1.206, df = 58, P > 0.05)在两种性别表型个体间无显著差异(图6, 图7)。大花百合两种性别表型植株花分配与总生物量均呈显著负相关关系(两性花植株: r = -0.464, P < 0.05; 雄花植株: r = -0.463, P < 0.05), 花分配随总生物量增加而减少, 二者线性回归关系显著(两性花植株: R2 = 0.22, P < 0.05; 雄花植株: R2 = 0.21, P < 0.05) (图8)。

图6

图6

大花百合两种性别表型植株各部分生物量干重。*** P < 0.001, 不同大写字母表示两性花植株和雄花植株对应的地上生物量、地下生物量和总生物量差异显著(P < 0.05) 。

Fig. 6

Dry weight of biomass of two sexual phenotypes of Lilium concolor var. megalanthum. *** P < 0.001. Different capital letters indicate significant differences in aboveground biomass, underground biomass, total biomass between hermaphrodite and male plant (P < 0.05).

图7

图7

大花百合两种性别表型植株生物量分配。** P < 0.01, 不同大写字母表示两性花植株和雄花植株对应的地上生物量分配和地下生物量分配有显著性差异(P < 0.05)。

Fig. 7

Biomass allocation of two sexual phenotypes of Lilium concolor var. megalanthum. ** P < 0.01. Different capital letters indicate significant differences in aboveground biomass allocation, underground biomass allocation between hermaphrodite and male plant (P < 0.05).

图8

图8

大花百合两种性别表型植株花分配与总生物量的回归关系

Fig. 8

Regression relationships between flower biomass allocation and total biomass of two sexual phenotypes of Lilium concolor var. megalanthum

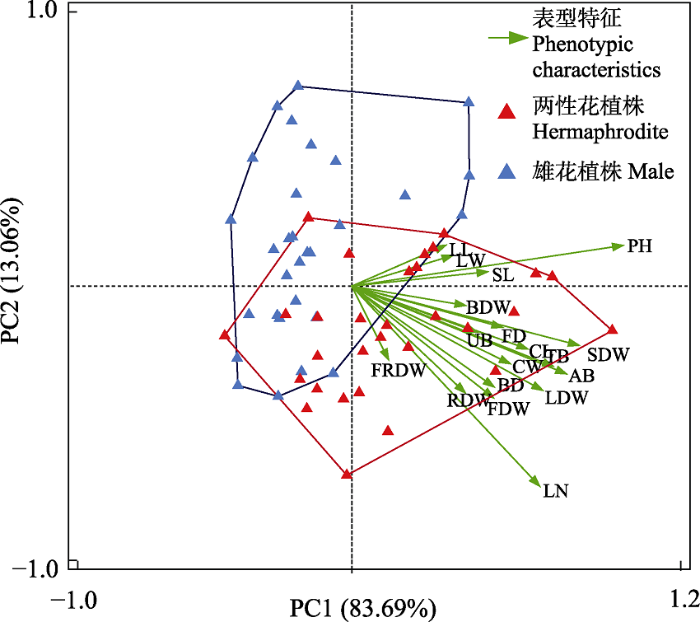

对大花百合的形态特征、生物量分配指标进行排序及对象分类, 雄花植株与两性花植株明显分开。PC1解释率为83.96%, PC2解释率为13.06%, PC1的差异主要由株高、叶数、地上生物量、总生物量、茎干重、叶干重、花干重、花瓣长、花瓣宽、花直径和基径贡献(图9)。

图9

图9

大花百合两种性别表型植株表型特征排序分类。PH: 株高; LN: 叶片数; LL: 叶长; LW: 叶宽; BD: 基径; FD: 花直径; CL: 花瓣长; CW: 花瓣宽; SL: 雄蕊长; SDW: 茎干重; LDW: 叶干重; FDW: 花干重; BDW: 鳞茎干重; RDW: 地下茎干重; FRDW: 须根干重; AB: 地上生物量; UB: 地下生物量; TB: 总生物量。

Fig. 9

Ordination and classification of phenotypic characteristics of two sexual phenotypes of Lilium concolor var. megalanthum. PH, Plant height; LN, Leaf number; LL, Leaf length; LW, Leaf width; BD, Base diameter; FD, Flower diameter; CL, Corolla length; CW, Corolla width; SL, Stamen length; SDW, Stem dry weight; LDW, Leaf dry weight; FDW, Flower dry weight; BDW, Bulb dry weight; RDW, Rhizome dry weight; FRDW, Fibrous root dry weight; AB, Aboveground biomass; UB, Underground biomass; TB, Total biomass.

两性花植株在个体大小方面的指标比雄花植株更大, 表明两性花植株需要积累更多的资源, 并能够更好地担负繁殖成本较高的雌性功能, 可见大花百合性表达与植株个体大小有关。

2.3 两种性别表型植株雄性功能差异

大花百合自花授粉的结籽率(F3,41 = 10.062, P <0.001)、坐果率(KW3 = 18.084, P < 0.001)均显著低于异花授粉和自然状态授粉处理。雄花和两性花作为花粉供体授给两性花后, 坐果率、结籽率差异不显著, 说明两性花兼具雌性和雄性功能, 花粉育性与雄花花粉无差别。另外, 各授粉处理的种子数量(F3,41 = 0.599, P > 0.05)、种子千粒重(F3,41 = 1.314, P > 0.05)、果荚长(F3,41 = 2.359, P > 0.05)、果荚宽(F3,41 = 1.266, P > 0.05)均无显著差异(表3)。对各授粉处理种子进行萌发实验, 结果表明不同授粉处理得到的种子在萌发率(KW3 = 3.206, P > 0.05)、初始萌发时间(KW3 = 4.878, P > 0.05)、萌发势(F3,12 = 1.069, P > 0.05)和萌发指数(F3,12 = 1.761, P > 0.05)方面均无显著差异(表4), 即不同授粉处理的种子存活率、萌发速度、萌发整齐度和种子活力均无显著差异。

表3 不同授粉处理条件下大花百合结实比较(平均值 ± 标准误)

Table 3

| 授粉处理 Pollination treatments | 种子数量 No. of seeds | 种子千粒重 Thousand-seed weight (g) | 结籽率 Seed set (%) | 坐果率 Fruit set (%) | 果荚长 Capsule length (cm) | 果荚宽 Capsule width (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 自花授粉 Self-pollination (N = 15) | 221 ± 33a | 1.73 ± 0.43a | 8.04 ± 3.22b | 53.33b | 2.26 ± 0.25a | 1.32 ± 0.09a |

| 自然状态授粉 Natural pollination (N = 16) | 235 ± 11a | 1.94 ± 0.15a | 46.45 ± 4.95a | 100a | 2.27 ± 0.11a | 1.37 ± 0.04a |

| 异花授两性花粉 Hermaphrodite-hermapheodite pollination (N = 13) | 264 ± 66a | 1.39 ± 0.17a | 52.03 ± 6.10a | 92.31a | 2.04 ± 0.16a | 1.34 ± 0.07a |

| 异花授雄性花粉 Male-hermapheodite pollination (N = 12) | 195 ± 18a | 1.66 ± 0.12a | 43.06 ± 6.40a | 100a | 1.86 ± 0.13a | 1.25 ± 0.04a |

同列不同字母表明差异显著(P < 0.05)

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05)

表4 不同授粉处理条件下所得大花百合种子的萌发特征(平均值 ± 标准误)

Table 4

| 授粉处理 Pollination treatments | 萌发率 Germination rate (%) | 初始萌发时间 Initial germination time (d) | 萌发势 Germination potential (%) | 萌发指数 Germination index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 自花授粉 Self-pollination (N = 15) | 95.84 ± 3.15a | 7.75 ± 0.25a | 24.17 ± 3.15a | 2.79 ± 0.15a |

| 自然状态授粉 Natural pollination (N = 16) | 95.83 ± 2.50a | 9.00 ± 0.58a | 25.83 ± 2.85a | 2.34 ± 0.07a |

| 异花授两性花粉 Hermaphrodite-hermapheodite pollination (N = 13) | 99.17 ± 0.83a | 8.75 ± 0.48a | 36.67 ± 7.20a | 2.61 ± 0.27a |

| 异花授雄性花粉 Male-hermapheodite pollination (N = 12) | 89.17 ± 5.67a | 9.00 ± 0.41a | 28.34 ± 6.74a | 2.21 ± 0.24a |

同列不同字母表明差异显著(P < 0.05)

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05)

3 讨论

3.1 大花百合的性系统类型和分布特征

大花百合一直被认为是两性花植物, 调查发现雄花在大花百合的自然种群中普遍存在。理论上, 两性花和雄花在个体水平上具有3种性别组合类型: 只具有两性花的个体、只产生雄花的雄性个体、雄花和两性花同株的个体。野外调查发现, 3种性别类型的个体都存在于大花百合的自然种群中, 其中两性花个体和雄花个体比较常见, 雄花和两性花同株的个体稀少。这一性表达类型与百合科豹子花属(Nomocharis)、洼瓣花属的植物情况类似①(①龚强帮 (2014) 百合科大小依赖性表达的时空格局及其适应意义. 硕士学位论文, 云南师范大学, 昆明.), 即自然种群中存在雄花植株、两性花植株和少量雄花两性花同株三种性表型个体。这样一来, 在大花百合种群中, 雄花可单独出现在一个植株个体上, 也可以和两性花同时出现在同一植株上成为“雄全同株”, 表现出雄全同株和雄全异株共同出现的现象。从不连续的两年调查结果看, 我们无法根据传统的性系统类型来定义大花百合的性系统, 因为其性表达格局不符合雄花和两性花组合的两种性系统类型即雄全同株或雄全异株。这是由于大花百合绝大多数植株每年只开一朵花, 开两朵花的植株稀少, 一个生长季内, 在种群水平上其表现为雄全异株的性二态系统。然而, 我们在室内利用种子萌发而成的大花百合苗, 从其生长开花情况来看, 证实了首次开花的大花百合植株绝大多数开雄花, 极少数鳞茎较大的个体开两性花。结合植株高度和野外调查数据,我们推测大花百合植株开花类型在连续年份间可能发生雄花和两性花的转变, 应算雄全同株的性二相系统, 这应该和已报道的具有雄全同株性系统的洼瓣花属的Lloydia serotine (Manicacci & Després, 2001)相似。植物的不同自然种群中, 不同性别表型的个体所占比例通常有所不同, 许多植物种群中或种群间出现连续的性表达格局, 常常被不同的研究者定义为不同的性系统(Barrett & Case, 2006)。我们根据Lloyd (1980)提出的表型性别的计算公式量化大花百合种群水平的性别分布, 大花百合具有雄花的个体充当父本, 通过花粉向下一代传递基因, 而具有两性花的个体可同时提供花粉和胚珠, 主要充当母本, 通过胚珠实现基因的传递。

2012年和2020年间金川泥炭沼泽湿地中大花百合种群总体表现为种群密度降低、雄花植株相对比例增加的趋势。大花百合结实能力和种子活力较强, 而自然更新受限, 我们推测其种群密度降低可能与其生境变化有一定联系。大花百合植株纤细, 种源较少, 其分布地常年呈干湿交替状态, 淹水时长、淹水深度及年际间土壤养分状态的波动都会影响植株的生长繁殖及性别表达。此外, 大花百合的传粉者种类和数量较少, 2020年观察发现主要为中华蜜蜂(Apis cerana cerana)与蓝灰蝶(Everes argiades), 雄花植株比例的增加可能利于增加异交, 提高授粉效率, 或者将有限的资源更多地投入到鳞茎贮备而进行无性繁殖。

3.2 大花百合个体大小与性表达

对大花百合两种花型植株的形态指标和生物量分配情况综合比较发现, 两性花植株个体要大于雄花植株, 也就是说植株生长达到一定大小才支持开两性花。两种性别表型植株花分配与总生物量线性回归显著, 表现为花分配随着总生物量增加呈线性下降趋势, 并且两性花植株花分配高于雄花植株花分配, 即两性花植株对花部投入高于雄花植株。对两种花型植株的表型特征进行的排序分析和对象分类结果显示, 大花百合雄花植株与两性花植株许多特征明显分开, 表明二者生长构件的形态特征和生物量分配有明显的差异, 其中主轴1 (PC1)的差异主要由株高、叶片数、地上生物量、总生物量、茎干重、叶干重、花干重、花瓣长、花瓣宽、花直径和基径贡献, 主轴2 (PC2)的差异主要由叶片数贡献, 两性花植株个体相比雄花植株拥有更大的主干部分, 这有助于占据更好的生态空间, 较多的叶片数也更有利于其进行光合作用积累资源, 而且较大的花部形态支持其兼具雌雄功能。这些结果揭示了大花百合符合个体大小依赖的性表达假说。

大花百合大的个体倾向于开一朵两性花或开两朵花(其中至少有一朵两性花), 小的个体倾向于开雄花或不开花。作为多年生植物, 大花百合不仅要面临当下繁殖和生长之间的资源权衡, 还要应对当下繁殖和未来繁殖之间的权衡。我们推测如果大花百合个体积累的资源满足其投入高成本的雌性功能的需求时, 植株便开两性花; 下一年度如果该个体的资源量不足以继续投入其雌性功能, 那么该个体可能只进行营养生长或只选择表达雄性功能。类似的情况还出现在百合属的开瓣百合(Lilium apertum)中, 其自然种群中出现雄花植株个体、两性花植株个体及雄花两性花同株个体3种性表型, 连续多年观察发现这些性别表型依据个体大小发生转换, 两性花植株比雄花植株大(Zhang et al, 2014)。但是, 大花百合植株在年际间是否会发生性别表达的变换, 目前还不得而知。学术界广泛接受的用来解释植物性别转换的假说是大小优势假说, 该假说认为植物自身的资源状况的年际间波动是导致其性别改变的根本原因(Freeman et al, 1980)。大花百合种群中这两类个体在不同年际间性别表型是否相互转变, 这需要对种群进行个体标记, 并对其性别表型进行连续多年跟踪观察才能确定。

大花百合两种花型植株的花分配差异不显著, 但两性花生物量显著大于雄花, 我们推测更大的两性花可以增加对传粉者的吸引力, 同时提高雌雄适合度。而雄花植株保持与两性花植株相近的花分配可能是为了保持其对传粉者的吸引力从而提高花粉传递的效率, 以弥补雌蕊退化造成的雌性功能的欠缺。雄花植株鳞茎干重与两性花植株相比无显著差异, 而鳞茎分配却显著高于两性花植株, 即雄花植株较两性花植株分配更多的资源给鳞茎。然而, 有些植物雌性个体在进化过程中通过生理和生态对策对高繁殖消耗进行补偿, 使得雌性个体的营养生长资源投入与雄性个体无差异(Rovere et al, 2003; Robakowski et al, 2018)。例如, 东北鼠李(Rhamnus schneideri)雌性个体较强的光合能力是对自身繁殖消耗的一种补偿机制, 弥补了较高的繁殖投入对营养生长的影响, 是雌性个体在较强的繁殖压力下做出的适应性改变(王俪玢等, 2020)。对新疆郁金香的一个两性花种群调查发现其繁殖成功率与植株鳞茎大小密切相关(Abdusalam et al, 2012)。多年生具鳞茎植物在生长季结束后, 地上部分枯萎, 地下鳞茎经过休眠越冬, 来年再从鳞片出芽更新, 可以实现无性繁殖。具有地下鳞茎的多年生植物(例如百合科), 大小依赖的性表达在其适应进化机制中可能尤为重要。我们推测大花百合雄花植株将更多资源分配给鳞茎进行无性繁殖。因此, 表达雌性功能的个体分配到营养生长的资源比例要低于雄性个体(Cedro & Iszkuło, 2011)。植物一旦具有多种性别表型(雄花和两性花), 就可以灵活地调节年际间种群内植株个体自身的性别类型, 从而改变种群中不同性别表型植株的比例, 也能使得部分小个体植株通过不开花来实现资源积累以便将来开花进行有性繁殖, 从而提高植株个体的繁殖适合度。大花百合作为多年生草本植物, 野外的开花个体常具有3种性表达类型, 我们推测其有可能通过年际间资源积累和性别转换来实现生长和繁殖资源之间的权衡, 这种性表达与资源分配策略的相互调节机制有待进一步研究。

3.3 大花百合性系统的适应意义

对大花百合进行不同授粉处理和对其种子进行萌发实验的结果表明: 雄花花粉并未比两性花花粉表现出更高的花粉可育性, 而且由雄花花粉和两性花花粉授粉获得的种子活力也无显著差异, 说明两性花兼具雌性和雄性两种功能, 且雄性功能与雄花相当, 未出现隐性雌雄异株现象。与大花百合类似的情况还出现在洼瓣花属的洼瓣花(Lloydia serotina) (Manicacci & Després, 2001)、郁金香属的Tulipa pumila (Astuti et al, 2020)和百合属的开瓣百合(Zhang et al, 2014)中, 这些植物的雄花花粉可育性并未高于两性花, 授粉结实情况并无差异。我们推测, 雄花的出现更有可能是资源条件受限时的一种折中策略。在授粉处理中, 大花百合自花授粉的结籽率、坐果率显著低于其他授粉方式, 这表明大花百合可能存在近交衰退, 自交也可能是在异交花粉不足时, 为大花百合提供了一种繁殖保障。如果未来的气候变化破坏了植物开花物候与传粉者活动的同步性, 自交繁殖也可能会成为一种相对重要的繁殖保障策略(McKee & Richards, 1998)。自然种群中相对较低的自交率以及不同授粉方式得到的种子育性差异不显著, 都在一定程度上保证了大花百合的结籽率和种子萌发率, 给植物提供了繁殖保障。

致谢

感谢东北师范大学宋传涛老师、研究生刘洋在野外调查中给予的帮助, 以及李振新老师和佟志军老师对部分数据分析的建议与帮助。

参考文献

Effects of vegetative growth, plant size and flowering order on sexual reproduction allocation of Tulipa sinkiangensis

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1003.2012.09064 URL [本文引用: 1]

新疆郁金香营养生长、个体大小和开花次序对繁殖分配的影响

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1003.2012.09064

[本文引用: 1]

植物有性繁殖与资源分配的关系研究对于揭示植物生活史特征及繁育系统进化具有重要意义。新疆郁金香(Tulipa sinkiangensis)是新疆天山北坡荒漠带特有的一种多年生早春短命植物。在自然生境中, 该物种仅以有性繁殖产生后代, 每株能产生1–8朵花, 且不同植株上的花数及果实数以及花序不同位置上的花与果实大小明显不同。本文通过对新疆郁金香有性繁殖与营养生长及植株大小的关系以及花序中不同位置花及果实间的资源分配研究, 旨在揭示营养生长、个体大小及开花次序对其繁殖分配的影响。结果表明: 在开花和果实成熟阶段, 新疆郁金香植株分配给营养器官(鳞茎和地上营养器官)与繁殖器官的资源间均存在极显著的负相关关系(PP<0.01), 说明新疆郁金香植株的繁殖分配存在大小依赖性。在具2–5朵花的新疆郁金香植株中, 花序内各花的生物量、花粉数和胚珠数、结实率、果实生物量、结籽数、结籽率及种子百粒重按其开花顺序依次递减, 说明花序内各花和果实的资源分配符合资源竞争假说。植株通过减少晚发育的花或果实获得的资源来保障早发育的花或果实获得较多的资源, 从而达到繁殖成功。

Boys and girls come out to play: The molecular biology of dioecious plants

DOI:10.1006/anbo.2000.1201 URL [本文引用: 1]

Male flowers in Tulipa pumila Moench (Liliaceae) potentially originate from gender diphasy

DOI:10.1111/psbi.v35.2 URL [本文引用: 1]

The evolution of plant sexual diversity

DOI:10.1038/nrg776 URL [本文引用: 3]

Darwin's legacy: The forms, function and sexual diversity of flowers

DOI:10.1098/rstb.2009.0212 URL [本文引用: 1]

The ecology and evolution of gender strategies in plants: The example of Australian Wurmbea (Colchicaceae)

DOI:10.1071/BT05151 URL [本文引用: 1]

Determinants of gender in Jack-in-the-pulpit: The influence of plant size and reproductive history

DOI:10.1007/BF00384456

PMID:28312103

[本文引用: 1]

Jack-in-the-pulpit, Arisaema triphyllum, is a perennial forest herb with the ability to change sex. At two sites in upstate New York, plant sex was correlated with plant size: males were smaller than females, nonflowering plants were smaller than males. Changes in plant size were accompanied by changes in sex. Sex change occurred quite frequently; at one site, 8% of nonflowering plants, 64% of males, and 63% of females changed their sex from one season to the next. The probability that a plant will change size and sex between years was altered by artificial defoliation and by the production of seeds, but was not affected by supplementing plants with nutrient fertilizer. Discriminant analysis indicated that several historical factors significantly affected plant sex: a model including the variables of current plant size, previous year's plant size, and previous year's sex was significantly better at predicting the current sex of individuals than was a model containing only current plant size. However, even the consideration of these three variables left up to a third of the plants misclassified with respect to gender. This analysis explains in part why plants at the two sites changed sex at different sizes, but it is likely that other factors-e.g. genetic differences-are involved.

Size-dependent sex allocation in a monocarpic perennial herb, Cardiocrinum cordatum (Liliaceae)

DOI:10.1007/s11258-007-9277-x URL [本文引用: 1]

Do females differ from males of European yew (Taxus baccata L.) in dendrochronological analysis?

DOI:10.3959/2009-9.1 URL [本文引用: 1]

The theory of sex allocation

Male flowers are better fathers than hermaphroditic flowers in andromonoecious Passiflora incarnata

DOI:10.1111/nph.2012.193.issue-3 URL [本文引用: 1]

Constraints imposed by pollinator behaviour on the ecology and evolution of plant mating systems

DOI:10.1111/jeb.12380

PMID:24750302

[本文引用: 1]

Most flowering plants rely on pollinators for their reproduction. Plant-pollinator interactions, although mutualistic, involve an inherent conflict of interest between both partners and may constrain plant mating systems at multiple levels: the immediate ecological plant selfing rates, their distribution in and contribution to pollination networks, and their evolution. Here, we review experimental evidence that pollinator behaviour influences plant selfing rates in pairs of interacting species, and that plants can modify pollinator behaviour through plastic and evolutionary changes in floral traits. We also examine how theoretical studies include pollinators, implicitly or explicitly, to investigate the role of their foraging behaviour in plant mating system evolution. In doing so, we call for more evolutionary models combining ecological and genetic factors, and additional experimental data, particularly to describe pollinator foraging behaviour. Finally, we show that recent developments in ecological network theory help clarify the impact of community-level interactions on plant selfing rates and their evolution and suggest new research avenues to expand the study of mating systems of animal-pollinated plant species to the level of the plant-pollinator networks. © 2014 The Authors. Journal of Evolutionary Biology © 2014 European Society For Evolutionary Biology.

Sex allocation and reproductive success in the andromonoecious perennial Solanum carolinense (Solanaceae). I. Female success

Relative allocation of resources to growth vs. reproduction has long been known to be an important determinant of reproductive success. The importance of variation in allocation to different structures within reproductive allocation is somewhat less clear. This study was designed to elucidate the importance of allocation to vegetative vs. reproductive functions, and allocation within reproductive functions (sex allocation), to realized female success in an andromonoecious plant, Solanum carolinense. Allocation measurements were taken on plants in experimental arrays exposed to natural pollination conditions. These measurements included total flower number, the proportion of flowers that were male, flower size, and vegetative size. Flower number explained the majority of the variation among individuals in their success-that is, there was strong selection for increased flower production. There was also selection to decrease the proportion of flowers that were male, but neither flower size nor vegetative size (a measure of overall resource availability) were direct determinants of female success. After Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons, most phenotypic correlations among the traits measured were nonsignificant. Thus, in this andromonoecious species there is not a strong relationship between resource availability (vegetative size) and female success, and female success is instead determined by the relative production of the two different flower types.

Sex change in plants: Old and new observations and new hypotheses

DOI:10.1007/BF00346825

PMID:28309476

[本文引用: 1]

Evidence is presented that individuals of a large number of dioecious and subdioecious plant species are able to alter their sexual state in response to changes in the ambient environment and/or changes in size or age. We suggest that lability of sexual expression probably has survival value where a significant portion of the females must otherwise bear the cost of fruit production in unfavorable environments. We demonstrate that in patchy environments of the proper scale and variability in quality, labile sexual expression will enhance an individual's genetic contribution to the next generation.

Male flowers and relationship between plant size and sex expression in herbaria of Nomocharis species (Liliaceae)

利用腊叶标本初探豹子花属植物的性表达及其与个体大小的关系

Geographic variation in primary sex allocation per flower within and among 12 species of Pedicularis (Orobanchaceae): Proportional male investment increases with elevation

DOI:10.3732/ajb.0900301 URL [本文引用: 1]

Fractals, random shapes and point fields: Methods of geometrical statistics

Advance in study on pollination biology

传粉生物学的研究进展

Pollen fertility and flowering phenology in an androdioecious tree, Fraxinus lanuginosa (Oleaceae), in Hokkaido, Japan

DOI:10.1086/314088 URL [本文引用: 1]

Reproductive biology and genetic structure in Lloydia serotina

DOI:10.1023/A:1009805401483 URL [本文引用: 1]

Self-pollen on a stigma interferes with outcrossed seed production in a self-incompatible monoecious plant, Akebia quinata (Lardizabalaceae)

DOI:10.1111/fec.2005.19.issue-1 URL [本文引用: 1]

Outcrossing rate and inbreeding depression in the perennial yellow bush lupine, Lupinus arboreus (Fabaceae)

Little is known about the breeding systems of perennial Lupinus species. We provide information about the breeding system of the perennial yellow bush lupine, Lupinus arboreus, specifically determining self-compatibility, outcrossing rate, and level of inbreeding depression. Flowers are self-compatible, but autonomous self-fertilization rarely occurs; thus selfed seed are a product of facilitated selfing. Based on four isozyme loci from 34 maternal progeny arrays of seeds we estimated an outcrossing rate of 0.78. However, when we accounted for differential maturation of selfed seeds, the outcrossing rate at fertilization was lower, ∼0.64. Fitness and inbreeding depression of 11 selfed and outcrossed families were measured at four stages: seed maturation, seedling emergence, seedling survivorship, and growth at 12 wk. Cumulative inbreeding depression across all four life stages averaged 0.59, although variation existed between families for the magnitude of inbreeding depression. Inbreeding depression was not manifest uniformly across all four life stages. Outcrossed flowers produced twice as many seeds as selfed flowers, but the mean performance of selfed and outcrossed progeny was not different for emergence, seedling survivorship, and size at 12 wk. Counter to assumptions about this species, L. arboreus is both self-compatible and outcrosses ∼78% of the time.

Functional androdioecy in the flowering plant Datisca glomerata

DOI:10.1038/343641a0 URL [本文引用: 1]

Sexual strategies in plants. III. A quantitative method for describing the gender of plants

DOI:10.1080/0028825X.1980.10427235 URL [本文引用: 2]

Modification of the gender of seed plants in varying conditions

Spatial distribution patterns of snag and standing trees in a warm temperate deciduous broad-leaved forest in Dongling Mountain, Beijing

北京东灵山暖温带落叶阔叶林枯立木与活立木空间分布格局

Floral sex ratio variation in hermaphrodites of gynodioecious Chionographis japonica var. kurohimensis Ajima et Satomi (Liliaceae)

DOI:10.1007/BF02344421 URL [本文引用: 1]

Male individuals in cultivated Fritillaria persica L. (Liliaceae): Real androdioecy or gender disphasy

Male and hermaphrodite flowers in the alpine lily Lloydia serotina

DOI:10.1139/b01-087 URL [本文引用: 3]

Cryptic dioecy in flowering plants

DOI:10.1016/0169-5347(91)90039-Z URL [本文引用: 1]

The effect of temperature on reproduction in five Primula species

DOI:10.1006/anbo.1998.0697 URL [本文引用: 1]

Subandrodioecy and male fitness in Sagittaria lancifolia subsp. lancifolia (Alismataceae)

Sagittaria lancifolia subsp. lancifolia is described as cosexual (monoecious), but the study population consisted of 84% cosexuals that typically had 35% pistillate buds and 16% predominant males that typically had 0-2% pistillate buds. Hand-pollinations showed that pistillate flowers required pollination to set seed, and pollen from both male and cosexual plants was potent. No gender switching was seen in the field or greenhouse. From 24 experimental crosses, 890 offspring were grown to maturity. Among these, all offspring of cosexual sires were cosexual, but approximately half the offspring of male sires were male, implying that maleness was inherited as a single, dominant allele. These results indicate that S. lancifolia is subandrodioecious, a very rare breeding system. It is rare, in part because its maintenance requires a large male-fitness differential between male and cosexual plants. In the study population, this condition was met by the differential survival of staminate buds on male racemes. Larvae of the weevil Listronotus appendiculatus killed many staminate buds. They did so in a vertical gradient, with buds lower on racemes safer. Male plants have replaced pistillate with staminate buds at these safer positions and thereby enjoy disproportionally higher male fitness.

Spatial patterns of seed dispersal, their determinants and consequences for recruitment

DOI:10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01874-7 URL [本文引用: 1]

Spatial distribution patterns and associations of main tree species in spruce-firforest in Changbai Mountains, northeastern China

长白山云冷杉林主要树种空间分布及其关联性

Function of male and hermaphroditic flowers and size-dependent gender diphasy of Lloydia oxycarpa (Liliaceae) from Hengduan Mountains

DOI:10.1016/j.pld.2017.06.001 URL [本文引用: 1]

The evolution and maintenance of androdioecy

DOI:10.1146/ecolsys.2002.33.issue-1 URL [本文引用: 1]

What is functional androdioecy?

DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.06893.x URL [本文引用: 1]

Males are cheaper, or the extreme consequence of size/age-dependent sex allocation: Sexist gender diphasy in Fritillaria montana (Liliaceae)

DOI:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2011.01204.x URL [本文引用: 3]

On the phylogenetic position and taxonomic value of Gagea trinervia (Viv.) Greuter and Gagea sect

Pollen production in the androdioecious Datisca glomerata (Datiscaceae): Implications for breeding system equilibrium

DOI:10.1111/psb.1994.9.issue-1 URL [本文引用: 1]

Sex choice and the size advantage model in jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum)

The relative and absolute frequencies of angiosperm sexual systems: Dioecy, monoecy, gynodioecy, and an updated online database

DOI:10.3732/ajb.1400196 URL [本文引用: 1]

Modelling spatial patterns

DOI:10.1111/rssb.1977.39.issue-2 URL [本文引用: 1]

Photochemistry and antioxidative capacity of female and male Taxus baccata L. acclimated to different nutritional environments

DOI:10.3389/fpls.2018.00742

PMID:29922316

[本文引用: 1]

In dioecious woody plants, females often make a greater reproductive effort than male individuals at the cost of lower growth rate. We hypothesized that a greater reproductive effort of female compared with male Taxus baccata individuals would be associated with lower female photochemical capacity and higher activity of antioxidant enzymes. Differences between the genders would change seasonally and would be more remarkable under nutrient deficiency Electron transport rate (ETRmax), saturation photosynthetic photon flux corresponding to maximum electron transport rate (PPFsat), quantum yield of PSII photochemistry at PPFsat (Phi PPFsat), and chlorophyll a fluorescence and activity of antioxidant enzymes were determined in needles of T. baccata female and male individuals growing in the experiment with or without fertilization. The effects of seasonal changes and fertilization treatment on photochemical parameters, photosynthetic pigments concentration, and antioxidant enzymes were more pronounced than the effects of between-sexes differences in reproductive efforts. Results showed that photosynthetic capacity expressed as ETRmax and Phi PPFsat and photosynthetic pigments concentrations decreased and non-photochemical quenching of fluorescence (NPQ) increased under nutrient deficiency. Fertilized individuals were less sensitive to photoinhibition than non-fertilized ones. T. baccata female and male individuals did not differ in photochemical capacity, but females showed higher maximum quantum yield of PSII photochemistry ((F)v/(F)m) than males. The activity of guaiacol peroxidase (POX) was also higher in female than in male needles. We concluded that larger T. baccata female reproductive effort compared with males was not at the cost of photochemical capacity, but to some extent it could be due to between-sexes differences in ability to protect the photosynthetic apparatus against photoinhibition with antioxidants.

Genetic diversity of wild lilies native to northeastern China by RAPD markers

东北地区野生百合遗传多样性的RAPD分析

Growth and climatic response of male and female trees of Austrocedrus chilensis, a dioecious conifer from the temperate forests of southern South America

DOI:10.1080/11956860.2003.11682767 URL [本文引用: 1]

Long-term study of a subdioecious Populus × canescens family reveals sex lability of females and reproduction behaviour of cosexual plants

DOI:10.1007/s00497-019-00378-5 URL [本文引用: 1]

Gender modification in North American ginsengs

DOI:10.2307/1310418 URL [本文引用: 2]

Size, gender, and sex change in dwarf ginseng, Panax trifolium (Araliaceae)

DOI:10.1007/BF00320425

PMID:28313704

[本文引用: 1]

Flowering individuals of dwarf ginseng may be either male or hermaphroditic. I recorded the sex expression and size of individuals in three populations for three or four years in order to 1) determine whether this bimodal distribution of sex expression was due to sex changing or genetic dimorphism, and 2) test predictions about a) the relationship between size and gender, and b) the association of size change and sex change. Twenty five to 37% of the flowering individuals in each population changed gender from one year to the next. Of the plants I followed for four years, 83% changed sex and 57% changed more than once. In each of these populations as well as two others, hermaphrodites were significantly larger than males. Gender dynamics of the three populations differed, but hermaphrodites tended to become smaller and were more likely to change gender than remain hermaphroditic the following year, whereas males tended to grow larger and were more likely to remain male than to change gender. Dwarf ginseng is clearly a diphasic (sex changing) species in which sex expression is determined primarily by size. A difference between genders in the immediate resource costs of reproduction appears to be an important determinant of sex change and gender phase ratios in populations.

Inbreeding, outbreeding, and heterosis in the yellow pitcher plant, Sarracenia flava (Sarraceniaceae), in Virginia

The yellow pitcher plant, Sarracenia flava, is an insectivorous plant restricted to fire-maintained wetland ecosystems in southeastern Virginia. Only four natural sites remain in the state totaling fewer than 100 clumps. Plants from sites located in Dinwiddie, Greensville, Prince George, Sussex counties, and the city of Suffolk were tested for the effects of self-pollination, intrasite outcrossing, and intersite outcrossing on offspring quantity (total seed number and total seed mass) and offspring quality (avarage seed mass, germination, and growth).Self-pollination resulted in significantly lower offspring quantity and quality. Total seed number and total seed mass for self-pollinated capsules were approximately one-fourth that of outcrossed capsules. Germination, survivorship, and growth over 5 yr were also significantly lower for offspring from self-pollinated capsules. Together, these results suggest strong inbreeding depression in this species.Relative to offspring from intrasite crosses, offspring from intersite crosses were significantly larger after 5 yr of growth. This suggests that restoration efforts for Virginia S. flava will be most successful when plants from multiple sites are used.

Effects of Nitrogen Input on Carbon and Nitrogen Transformations in Peatlands

PhD dissertation, Northeast Normal University, Changchun.

氮输入对泥炭沼泽碳氮转化的影响研究

博士学位论文, 东北师范大学, 长春.]

Selection through female fitness helps to explain the maintenance of male flowers

Andromonoecy, the production of both male and hermaphrodite flowers in the same individual, is a widespread phenomenon that occurs in approximately 4,000 species distributed in 33 families. Hypotheses for the evolution of andromonoecy suggest that the production of intermediate proportions of staminate flowers may be favored by selection acting through female components of fitness. Here we used the andromonoecious herb Solanum carolinense to determine the pattern of selection on the production of staminate flowers. A multivariate analysis of selection indicates that selection through female fitness favors the production of staminate flowers in at least one population. We conclude that this counterintuitive benefit of staminate flowers on female fitness highlights the importance of considering female components of fitness in the evolution of andromonoecy, a reproductive system usually interpreted as a "male" strategy.

Self-incompatibility and male fertilization success in Phillyrea angustifolia (Oleaceae)

Androdioecy is a rare breeding system in which low male frequency is expected in populations because males require a strong increase in their fertility to be maintained by selection. Phillyrea angustifolia L. has previously been reported as possibly functionally androdioecious. However, 1&rcolon;1 sex ratios have been reported and suggest functional dioecy. In this article, we compared both pollen tube growth and siring success of male and hermaphrodite pollen in two single-donor pollination experiments. We verified at both pre- and postzygotic levels that hermaphrodites produce functional pollen. Self-incompatibility was also clearly established. However, pollen from hermaphrodites was less efficient than male pollen. The probability of a pollen tube growing through the style was higher for male than for hermaphrodite pollen donors, and males sired twice as many fruits as hermaphrodites. The twofold male advantage in relative fecundity was mainly because of lower pollen fertility of hermaphrodites and possible cross-incompatibility among hermaphrodites.

Temporal variation of plant sexes in a wild population of Tulipa sinkiangensis over seven years

DOI:10.17520/biods.2018038

[本文引用: 1]

Understanding the variation in plant sexual strategies provides insights into the evolution of plant sexual systems. In hermaphrodite plants, floral gender is thought to be a plastic response that allows individuals to vary resource allocation to both female and male function under variable environmental conditions. Tulipa sinkiangensis is known to be hermaphroditic, early spring ephemeral plant, but our preliminary investigation showed that some populations had perfect flowers whereas other populations had staminate flowers. To understand correlates of occurrence and temporal variation of staminate flowers in T. sinkiangensis, we examined flower sex and its variation among individuals in a population of nearly 1,000 plants in Xinjiang, northwestern China from 2011 to 2017. (1) In the study population one-flower and two-flower plants comprised 74.5% (4,373) and 23.0% (1,358) of all flowering individuals (5,863), respectively. Sex differentiation was seen primarily in drier areas with shallow soils. Perfect and staminate flowers randomly occurred on different plants, constituting a hermaphroditic based population with some male and andromonoecious individuals. (2) Compared to perfect flowers, staminate flowers appeared later within individual plants and in the whole population during flowering. Staminate flowers were smaller and had aborted ovaries without visible ovules. However, pollen number and size, pollen morphology and fertility were not significantly different from perfect flowers when the two floral morphs were the same size. (3) During 2011 to 2014 of the study period, percentage of staminate flowers in the population declined from 23.4% to 3.1% but remained at stable (1.5% to 1.0%) from 2015 to 2017. The number of one-flower plants and two-flower plants fluctuated with time. (4) Our observations suggest that the production of staminate flowers in this endemic tulip flower was likely a plastic response to plant resource status, environmental conditions and other ecological factors.

新疆郁金香一居群个体性别7年的动态变化

DOI:10.17520/biods.2018038

[本文引用: 1]

在雌雄同株植物中, 花性别被认为是两性资源分配对环境条件的响应, 了解个体性别随时间的变化对探讨植物性系统的变异有重要意义。早春短命植物新疆郁金香(Tulipa sinkiangensis)多为两性花居群, 前期调查显示一些居群由雄花和两性花构成。为了探讨新疆郁金香雄花的发生与变化, 我们连续7年对一个居群的花性别及其变化动态进行了跟踪。结果显示: (1)该居群主要是由一朵花植株和两朵花植株构成, 分别占居群植株总数的74.5%和23.0%。两种性别的花随机分布在不同类型的单株上, 形成了以两性花植株为主, 含有雄株、雄花与两性花同株(andromonoecy)的居群结构。(2)雄花相对较小, 子房退化, 无胚珠发育, 在植株或居群中花期较晚出现。与相同大小的两性花相比, 雄花在单花花粉量、花粉败育率、花粉粒大小及形态、雄性功能等方面没有差异。(3) 7年间, 雄花在居群中的比例经历了2011-2014年间的显著下降(23.4-3.1%)和2015-2017年间相对稳定的零星分布(1.5-1.0%)两个阶段。居群中一朵花植株数量和两朵花植株数量在年份间呈波动性变化。(4)雄花的出现可能是植株受自身资源状况及环境条件等因素的影响在花性别选择上作出的可塑性反应。

Study on gender differentiation of reproduction cost in Rhamnus schneideri var. manshurica

东北鼠李生殖耗费的性别分异研究

Sex ratio and spatial pattern of Eurya loquaiana population in Jinyun Mountain

缙云山细枝柃种群性比及空间分布

The avoidance of interference between the presentation of pollen and stigmas in angiosperms II. Herkogamy

DOI:10.1080/0028825X.1986.10409726 URL [本文引用: 1]

The different forms of flowers-What have we learned since Darwin?

DOI:10.1111/boj.2009.160.issue-3 URL [本文引用: 1]

Variation and evolution of sex ratios at the northern range limit of a sexually polymorphic plant

DOI:10.1111/jeb.12322

PMID:24506681

[本文引用: 1]

Gender strategies involve three fundamental sex phenotypes - female, male and hermaphrodite. Their frequencies in populations typically define plant sexual systems. Patterns of sex-ratio variation in a geographical context can provide insight into transitions among sexual systems, because environmental gradients differentially influence sex phenotype fitness. Here, we investigate sex-ratio variation in 116 populations of Sagittaria latifolia at the northern range limit in eastern N. America and evaluate mechanisms responsible for the patterns observed. We detected continuous variation in sex phenotype frequencies from monoecy through subdioecy to dioecy. There was a decline in the frequency and flower production of females in northerly populations, whereas hermaphrodite frequencies increased at the range limit, and in small populations. Tests of a model of sex-ratio evolution, using empirical estimates of fitness components, indicated that the relative female and male contribution of males and hermaphrodites to fitness is closer to equilibrium expectations than female frequencies. Plasticity in sex expression and clonality likely contribute to deviations from equilibrium expectations. © 2014 The Authors. Journal of Evolutionary Biology © 2014 European Society For Evolutionary Biology.

Growth habits and artificial domestication cultivation techniques of Lilium megalanthum in Changbai Mountain area

长白山区大花百合生长习性与人工驯化栽培技术

Linking the pollen supply patterns of Ficus tikoua to its potential suitable areas and key environmental factors

地果花粉供应格局成因和适生区分析

Size-dependent resource allocation and sex allocation in herbaceous perennial plants

DOI:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00369.x URL [本文引用: 1]

Adaptive significances of sexual system in andromonoecious Capparis spinosa (Capparaceae)

刺山柑雄全同株性系统的适应意义

Floral sex allocation and flowering pattern in the andromonocious Soranthus meyeri (Apiaceae)

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1258.2012.00063 URL [本文引用: 1]

雄全同株植物簇花芹花期性别分配与开花式样

Size-dependent gender modification in Lilium apertum (Liliaceae): Does this species exhibit gender diphasy?

DOI:10.1093/aob/mcu140 URL [本文引用: 4]