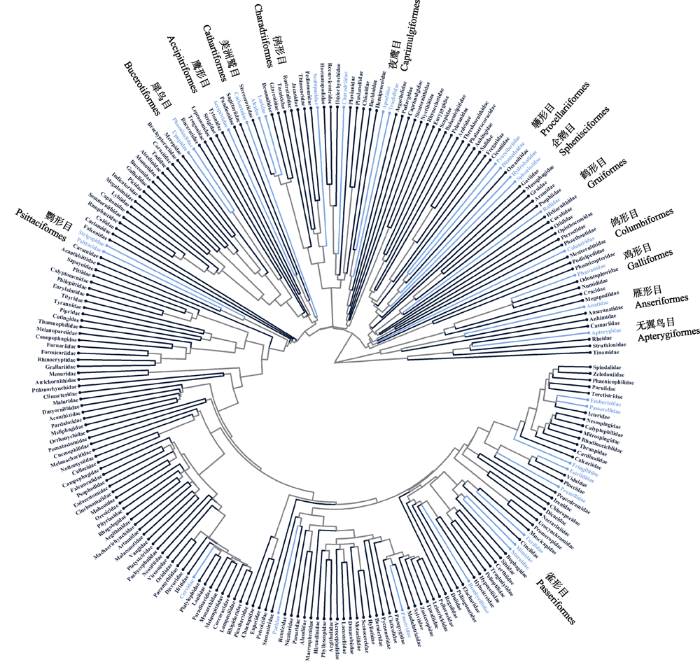

在生物所处的环境中, 化学信号几乎无处不在。作为古老的感觉通路, 嗅觉对动物的生存和繁衍具有关键作用(Patel & Pinto, 2014)。但一百年以来的主流观点是: 除了某些物种外, 鸟类主要依靠视觉和听觉进行交流, 几乎已经丧失嗅觉(Stager, 1967)。多数早期研究缺乏合理的设计, 且受到实验对象和手段的限制, 因此得到相互矛盾的结果(Audubon, 1826; Hill, 1905; Walter, 1942)。20世纪下半叶, 一些常见物种的嗅觉能力逐渐被揭示出来(Abankwah et al, 2020)。近年来, 科学家通过新的技术手段获得了解剖学(Bang, 1971)、电生理学(Corfield et al, 2015)、分子生物学(Driver & Balakrishnan, 2021)、化学检测和分析(Nevitt & Prada, 2015)、行为学实验(Mäntylä et al, 2020)等方面的证据, 进一步证明了鸟类嗅觉的存在。目前的相关研究证实, 嗅觉通讯存在于14目33科的鸟类中(图1), 使科学界重新认识嗅觉在鸟类感官中的重要作用。而我国这一领域的研究长期被忽视, 目前仅有对于笼养的白腰文鸟(Lonchura striata, Zhang et al, 2009)、虎皮鹦鹉(Melopsittacus undulatus; Zhang et al, 2010)、小太平鸟(Bombycilla japonica)与太平鸟(B. garrulus, Zhang et al, 2013)、信鸽(Columba livia domestica; Li et al, 2016; 于丛等, 2021)的研究报道。为此, 我们结合近年来的研究进展, 综述鸟类嗅觉在物种和个体识别、繁殖行为、亲缘识别、配偶选择与竞争等方面发挥的作用, 同时提出当前的研究局限性, 并强调整合研究在该领域的重要意义。

图1

图1

鸟类科级别的系统进化树。标注为蓝色的部分为目前研究中存在嗅觉通讯相关证据的物种所在的14目33科。建树采用国际鸟盟(BirdLife International)的分类(11,009个物种, 243个科)作为骨架, 绘图在R语言4.1.3中使用程序包ggplot2和ggtree完成。

Fig. 1

The phylogenetic tree for all bird families. Species in 14 orders and 33 families with evidence of olfactory communication in current studies are marked in blue. The tree was built under the taxonomy of BirdLife International (11,009 species in 243 families), and the mapping was done in R 4.1.3 using the packages ggplot2 and ggtree.

1 嗅觉系统的生理依据及功能

许多鸟类的嗅上皮组织(olfactory epithelium)、嗅觉神经(olfactory nerve)和嗅球(olfactory bulb)都发育完好。鸟类嗅上皮组织中存在感知气味分子的嗅觉受体(olfactory receptor, OR)。编码OR的基因主要属于γ-c亚家族的大型分支, 而该基因家族的扩张是鸟类的共同特征(Steiger et al, 2008)。使用三代测序技术, 研究人员在来自5个物种的10个基因组组装中发现了1,496个OR基因; 其中, γ-c亚家族占65%以上, 表明嗅觉受体基因在鸟类中具有高度多样性(Driver & Balakrishnan, 2021)。气味刺激可引发鸟类的嗅觉神经纤维、嗅球和大脑其他部位产生相应的动作电位(Caro et al, 2015)。而嗅球是大脑中负责处理嗅觉信息的第一个部位, 可以将接收到的气味信息投射到多个大脑区域(Golüke et al, 2019)。嗅球的体积在不同鸟类中存在巨大差异(Bang, 1971), 反映了不同物种在异速生长、生态与系统发育方面的多样性(Corfield et al, 2015)。除嗅觉系统外, 位于鸟类第四节尾椎到尾综骨之上的尾脂腺(preen gland或者uropygial gland)分泌出由不同酯质组成的复杂油性物质, 是鸟类体味的主要来源(Campagna et al, 2011)。其成分受多种因素的影响, 并具有许多潜在功能(详见综述: Moreno-Rueda, 2017)。另外, 微生物群落的组成和结构可能也参与了特定气味的调节(Maraci et al, 2018)。对于嗅觉通讯生理和神经层面的机理, 本文不做展开。

2 嗅觉通讯在社会行为中的作用

2.1 物种、亚种与种群识别

实验发现, 鸟类气味可成为介导种间识别的线索。在灰蓝灯草鹀(Junco hyemalis)中, Whittaker等(2009)利用异种(非捕食者)和同种个体的气味对野外个体进行了对比实验; 相较于同种气味, 暴露于异种气味的雌鸟显著缩短了孵卵的时间。在异种(非捕食者)气味的对比下, 红玫瑰鹦鹉(Platycercus elegans)表现出明显的同种气味偏好(Mihailova et al, 2014)。亲缘关系较近的两个物种——同域分布的太平鸟和小太平鸟(Zhang et al, 2013)、群居的斑胸草雀(Taeniopygia guttata)和独栖的斑胁火尾雀(Stagonopleura guttata) (Krause et al, 2014)、杂交带内的黑顶山雀(Poecile atricapillus)和卡罗山雀(P. carolinensis) (Van Huynh & Rice, 2019)——也在实验中表现出种间气味识别的现象。这些结果表明, 鸟类的气味和嗅觉或许是被学者长期忽略的重要线索。基于嗅觉的种间交流可能会促进交配前的生殖隔离, 进而影响种群分化与物种形成。有趣的是, 尽管斑胸草雀展现出强烈的同种偏好, 但斑胁火尾雀并未做出区分二者气味的行为。研究人员推测, 嗅觉线索对物种识别的重要性受到生态、生理或进化方面的影响, 因而在群居鸟类中更为突出(Krause et al, 2014)。

2.2 个体与鸟巢识别

信鸽归巢的研究已有数十年的历史, 同时涉及鸟类嗅觉的社会交流(鸟巢识别)与导航功能。这种经过长期人工选择的鸟类可以长距离飞行, 并能在被转移到其他地方后准确地返回鸟舍。Wallraff (1970)发现鸟舍所在地的某种大气因素似乎影响了它的嗅觉能力, 并推断嗅觉与信鸽的归巢能力有关。通过切除信鸽的嗅觉神经, Papi等(1972)发现丧失嗅觉的个体无法归巢, 从而提出了著名的嗅觉导航假说(Olfactory Navigation Hypothesis): 信鸽在鸟舍中学习风向与风携带的气味, 建立起鸟舍附近一定区域内的嗅觉地图; 一旦改变位置, 它们就会根据当地的环境气味来判断鸟舍的方向。这一假说震惊了该领域的学者, 也是动物学界最激烈的争论之一(Gagliardo, 2013)。尽管越来越多的证据支持嗅觉线索在信鸽归巢中的作用(Gagliardo et al, 2011, 2018), 但其合理性和真实性也一直备受争议(Mora et al, 2004; Jorge et al, 2010)。国内的研究表明, 空气污染程度显著影响信鸽归巢的速度; 这可能是由于归巢动机的增强或丰富的嗅觉环境促进了信鸽对鸟巢的识别(Li et al, 2016; 于丛等, 2021)。

除了信鸽之外, 鹱形目海鸟由于穴居、集群繁殖和夜间归巢等特殊习性, 也是个体与鸟巢识别的主要研究对象。在经历长时间、长距离的外出觅食后, 多种鹱形目鸟类能利用气味重新定位到自己筑巢的洞穴(Belliure et al, 2003; Bonadonna et al, 2003; Bonadonna & Nevitt, 2004)。研究人员利用Y形迷宫装置对这些海鸟进行了各项双选实验。其中, 暴风海燕(Hydrobates pelagicus)的雏鸟能够在其他同种雏鸟的对比下辨认出自己的气味(Belliure et al, 2003)。鸽锯鹱(Pachyptila ata)和蓝鹱(Halobaena caerulea)都会被配偶的气味所吸引; 此外, 当存在其他同种个体(包括自己的配偶)的气味时, 这两种海鸟都会回避自身的气味(Bonadonna & Nevitt, 2004; Mardon & Bonadonna, 2009)。研究人员推测, 这种体现在嗅觉上的自我回避超越了个体识别的范畴, 可能与亲缘识别和避免近亲交配有关, 也可能在该类群中普遍存在, 需要进一步的讨论。

之后关于鸟巢识别的研究拓展到了具有社会性的梅花雀科鸟类当中。这些研究对象与鹱形目海鸟拥有一个共同的特点——集群繁殖。对于该类群而言, 雏鸟和亲鸟都有精准定位鸟巢的需要, 以保障自身的存活率和繁殖成功率(Mariette & Griffith, 2012)。斑胸草雀和笼养鸟‘十姊妹’ (Lonchura striata domestica, 是白腰文鸟与其他梅花雀科鸟类杂交而来的宠物鸟品种)都更喜欢自己鸟巢的气味(Caspers & Krause, 2011; Krause & Caspers, 2012)。不过, 这种偏好只出现在雏鸟和雌性亲鸟身上; 当雏鸟初飞后, 雌鸟对任意鸟巢气味的行为反应都有所减少。这表明鸟巢识别具有某种程度的性别特异性, 并受到后代发育阶段的影响(Krause & Caspers, 2012)。Caspers等(2013)通过对鸟卵的转移孵化进一步探究了嗅觉记忆的获得机制。结果表明, 鸟巢识别是雏鸟在孵化前后的一个狭窄时间窗口内所产生的嗅觉印记, 并非与生俱来。此外, 斑胸草雀和蓝鹱的雌鸟也表现出识别卵气味的能力(Golüke et al, 2016; Leclaire et al, 2017a)。对于鸟巢、卵、配偶与自身的气味识别, 或许这些相关现象背后具有统一的气味信号, 但对于具体的机理仍然值得深入探究。

2.3 亲缘识别

为了避免近亲繁殖或加强群体内个体间的合作, 家庭成员识别彼此的能力可能普遍存在于动物界中。例如, 具有归家性(natal philopatry)的动物会回到熟悉的出生地, 虽然避免了寻找新繁殖地带来的相关风险和成本, 但也提高了近亲繁殖的概率(Cava et al, 2016)。而亲缘识别正是近交回避的主要机制之一(Bonadonna & Sanz-Aguilar, 2012)。此外, 亲缘识别也是亲缘选择和利他行为的基础, 对动物的适合度(fitness)具有非常重要的意义(Breed, 2014)。亲缘识别至少由两种机制介导: (1)通过社会互动, 动物在早期发育过程中学习相关个体(如父母、兄弟姐妹)的表型, 然后将熟悉与不熟悉的个体区分开来, 即先验关联(prior association); (2)动物学习自己的表型和/或熟悉的亲属的表型, 然后将未知个体的表型与学习到的模板进行比较或匹配, 即表型匹配(phenotype matching)。虽然这两种机制都涉及到表型和模板之间的对比, 但先验关联只能令个体识别之前遇到过的熟悉个体, 而表型匹配可以通过模板的泛化来识别不熟悉的亲属(Schausberger, 2007)。

部分鸟类运用视觉和听觉线索进行亲缘识别(Caspers & Krause, 2013)。而老鼠为鸟类嗅觉在其中的作用提供了最早的证据。Célérier等(2011)利用老鼠的敏锐嗅觉来识别蓝鹱个体的气味, 发现雏鸟与其亲鸟之间存在高度的相似性, 间接证实了亲缘气味标签的存在。此后, 研究者开始对具有归家性或群居性的鸟类进行嗅觉亲缘识别的实验。秘鲁企鹅(Spheniscus humboldti)和暴风海燕都更喜欢非亲属个体的气味, 符合近交回避的假设(Coffin et al, 2011; Bonadonna & Sanz-Aguilar, 2012)。家麻雀(Passer domesticus)雌鸟则强烈地避开非亲属的熟悉雄鸟的气味, 支持先验关联的机制(Fracasso et al, 2018)。Caspers等(2015)为嗅觉丧失(实验组)和嗅觉完好(对照组)的斑胸草雀雌鸟同时提供了没有亲缘关系的雄鸟和同父同母的雄鸟, 得到了令人意外的结果: 对照组中的部分雌鸟(37.5%)对雄鸟表现出强烈的攻击行为, 导致实验不得不提前终止; 而实验组则没有出现类似的现象。最终, 实验组的产卵数量和繁殖成功率(可独立生活的后代占比)明显高于对照组。亲属气味的存在对雌鸟的繁殖行为产生了重大的影响, 再次表明气味信号可能具有阻止近亲交配的潜在功能。

在亲代与后代互动的背景下, 一些关于鸟类嗅觉的实证研究也陆续出现。斑胸草雀的雏鸟可以识别亲鸟的气味, 雄鸟也可以根据气味线索识别自己的后代(Krause et al, 2012; Caspers et al, 2017; Golüke et al, 2021)。Caspers等(2017)交换了来自不同鸟巢的卵, 探究孵化后的雏鸟对其生物学父母和养父母的嗅觉反应。结果表明, 即便在孵化后没有与亲本建立联系, 雏鸟依然能在生物学母亲的气味刺激下表现出更强的乞食反应, 体现了亲子冲突。另一方面, 与熟悉的气味相比, 闻到非亲缘关系的雏鸟气味的青山雀(Cyanistes caeruleus)雏鸟会表现出更强烈且持续时间更长的乞食行为(Rossi et al, 2017)。这一结果表明, 巢中雏鸟的亲缘度同样会影响个体的乞食强度, 符合亲缘选择对自私和利他行为的预测。然而, 并非所有研究都得到了显著的结果。在Amo等(2014)的研究中, 雌性纯色椋鸟(Sturnus unicolor)没有在自己的后代和其他雏鸟之间表现出明显的气味偏好。

2.4 求偶和繁殖行为

目前, 关于鸟类利用嗅觉进行性别区分的研究共有10余项, 但结果并不一致。灰蓝灯草鹀(Whittaker et al, 2011)和纯色椋鸟(Amo et al, 2012a)的雌鸟和雄鸟都更偏向于雄性的气味。针对虎皮鹦鹉(Zhang et al, 2010)和红玫瑰鹦鹉(Mihailova et al, 2014)的研究只发现了雌鸟对雄性气味的选择偏好。而歌带鹀(Melospiza melodia; Grieves et al, 2019a)、黑顶山雀和卡罗山雀(Van Huynh & Rice, 2019)的雄鸟和雌鸟接近异性气味的时间都比同性更多。此外, 关于鸽锯鹱(Bonadonna et al, 2009)和家朱雀(Haemorhous mexicanus; Amo et al, 2012b)的研究没能找到性别区分的证据。值得指出的是, 上述实验都是在鸟类的繁殖状态下进行的。虽然多数结果都体现出明显的雌性选择导向, 也无法区分雌性对雄性气味的偏好是来源于异性信息素的吸引力、对同性气味的回避还是单纯的习惯化, 但它们确实在某种程度上证明了鸟类具有利用嗅觉区分性别的能力。

既然鸟类的气味普遍存在性别差异, 也能为同种个体提供区分性别的线索和繁殖唤起的信号, 那么在繁殖期中, 气味的化学成分或许包含着配偶选择与竞争所需要的复杂信息。Grieves等(2022)提出了性化学信息素假说(Sex Semiochemical Hypothesis), 即尾脂腺分泌物的性别差异与鸟类在繁殖过程中的交流和配偶选择有关。通过系统发育比较分析, 他们发现尾脂腺分泌物成分的性别差异更常见于繁殖季节(Grieves et al, 2022)。事实上, 灰嘲鸫(Dumetella carolinensis; Shaw et al, 2011)和白喉带鹀(Zonotrichia albicollis; Tuttle et al, 2014)等雀形目鸟类的尾脂腺分泌物在繁殖期变得更具挥发性, 与嗅觉隐蔽假说(Olfactory Crypsis Hypothesis)相悖(Grieves et al, 2022)。气味线索的增强可能有助于个体寻找配偶和/或与同性个体竞争, 类似于哺乳动物的领地气味标记(Nie et al, 2012)。这些信号可能会强化其他与性别、繁殖状态或优势地位相关的性状, 比如鸣唱、羽毛及其他受性选择作用的装饰(Bonadonna & Mardon, 2013; Grieves et al, 2022)。

与其他动物一样, 鸟类也需要挑选合适的配偶, 保障后代的质量, 从而令自身的广义适合度(inclusive fitness)最大化; 相反, 错误的选择会带来高昂的代价。在这一过程中, 选择者可能会倾向于基因优良(good genes)的求偶者, 比如拥有某些等位基因(或组合)或基因杂合性(heterozygosity)较高的个体; 它们也可能会青睐具有遗传相容性(genetic compatibility)或拒绝基因相似的求偶者(Rosenthal & Rosenthal, 2017)。其中, 动物体内的主要组织相容性复合体(major histocompatibility complex, MHC)基因通过编码细胞表面的蛋白质来识别和结合非自身抗原, 在免疫系统中发挥重要的作用, 且具有高度多态性。通过识别和选择具有不同MHC基因的配偶, 或者直接选择MHC基因杂合性更高的配偶, 特定个体可以增强后代的免疫能力和避免近亲繁殖, 从而提高自己的适合度(Winternitz et al, 2017)。

近10年来, 学者们逐渐获得了一些令人振奋的成果。Whittaker等(2013)在灰蓝灯草鹀的尾脂腺中发现, 一些与性别差异相关的气味化合物浓度(下文简称为“雄/雌性特征”)随着个体的繁殖成功率而变化: 雄性特征更强的雄鸟和雌性特征更强的雌鸟都能产生更多的后代。此外, 雄性特征较强的雄鸟拥有更高的后代存活率(包括婚外配所产生的雏鸟); 而雌性特征较强的雄鸟更有可能面临配偶“出轨”的风险, 导致巢中的父权比例下降。这项研究首次将鸟类的嗅觉线索与个体的适合度联系在一起。随后, 气味线索与个体的基因构成也出现了关联性证据。在三趾鸥(Rissa tridactyla; Leclaire et al, 2014)和歌带鹀(Slade et al, 2016)中, 如果异性个体间的尾脂腺分泌物成分越相似, 它们的MHC基因也就越相似; 这表明尾脂腺分泌物可能提供了关于亲缘关系或选型交配的线索。行为双选实验表明, 歌带鹀更喜欢MHC基因不相似或多样性更高的异性的气味(Grieves et al, 2019b)。蓝鹱也同样能通过嗅觉检测到异性个体的MHC基因相似性(Leclaire et al, 2017b)。求偶场的雄性尖尾娇鹟(Chiroxiphia lanceolata)不为后代提供任何的亲代抚育, 但它们的繁殖成功率和后代存活率都随着其微卫星分子标记的杂合度的增加而增加(Sardell et al, 2014)。此外, 雄鸟分泌的挥发性成分特征反映了它们的基因杂合性, 表明雌鸟可以利用气味线索来评价雄鸟的遗传质量(Whittaker et al, 2019)。

在配偶选择之外, 繁殖背景下的同性竞争似乎还缺乏直接的证据。在上一节提到的性别区分实验中, 家朱雀雄鸟似乎无法辨别两性的气味; 但后验分析发现, 如果实验个体的质量低于雄性气味供体, 它们就会选择避开, 反之则靠近(Amo et al, 2012a)。此外, 7种繁殖状态下的雌鸟都选择了接近雄鸟的气味(Amo et al, 2012b; Mihailova et al, 2014; Grieves et al, 2019a; Van Huynh & Rice, 2019)。这究竟是因为对异性信号的偏好, 还是对同性信号的排斥? 目前的研究结果还无法具体地阐明这个问题, 但鸟类嗅觉作为配偶选择的线索并与个体的遗传质量存在关联的证据已经初见端倪。

根据上文总结的研究, 基于气味的性别区分和配偶选择实验大多将雄鸟散发的吸引和/或竞争信号视为性选择的焦点, 因而表现出明显的雌性选择导向。这一现象与动物研究史上的性别偏倚(sex-biased)高度重合——学者曾经聚焦于雄性动物的装饰、鸣声和求偶炫耀, 后来才发现同样的信号在雌性中也相当普遍(Amundsen, 2000)。于是, Whittaker和Hagelin (2021)指出了化学性二型(chemical dimorphism)中的雌性偏重: 在气味这一领域中, 雌鸟才是更为“浓郁”的一方。根据目前发表的相关研究, 基于雌性的化学交流模式通常体现在3个方面: (1)体积更大的尾脂腺; (2)更多的挥发性或半挥发性化合物(以相对或绝对丰度衡量); (3)在尾脂腺分泌物中, 更高的组分多样性或微生物多样性(Whittaker & Hagelin, 2021)。他们认为, 这种模式或许是某些社会功能的基础, 比如在两性间对雌鸟的性接受或质量进行宣告(包括对雄鸟的生理启动效应)、性别内部的竞争(包括气味标记和生殖抑制)、亲代行为(比如亲子识别和对卵、雏鸟的化学保护)等(Whittaker & Hagelin, 2021)。因此, 研究人员应调整传统的研究范式, 侧重从雌性化学信号的角度来探究鸟类的社会行为。

3 展望

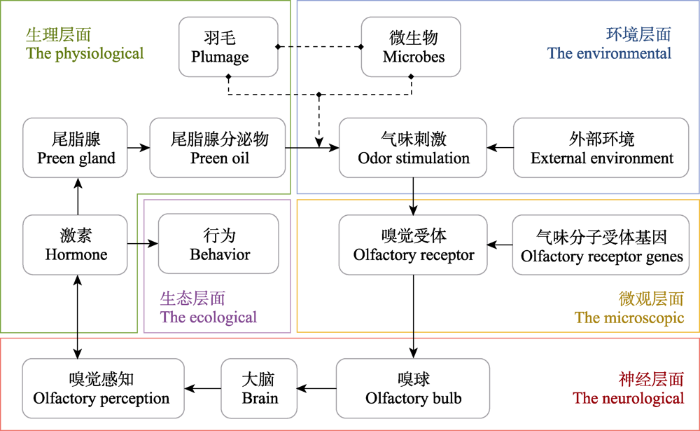

根据气味信号的产生到其所引发的神经刺激, 本文提出鸟类嗅觉通讯的研究框架, 可归纳为5个层面, 分别为环境、生理、微观、神经和生态(图2)。当前的研究多集中于一两个层面, 主要为生理和生态层面。尽管尾脂腺是散发气味的重要器官, 但目前仍缺乏与特定功能相关的活性成分的鉴定。此外, 生理层面的相关工作也较少考虑激素的作用。在生态层面的各项行为实验中, 对气味偏好的测试还停留在较为粗浅的识别阶段, 未能将关于嗅觉的行为与特定个体或野外种群的适合度联系在一起, 以证明嗅觉功能的生态学意义。关于环境、微观和神经层面的研究相对缺乏。体表微生物群落的作用和转移可能是鸟类气味的重要影响因素, 但始终缺乏有力的证据; 对鸟类尾脂腺或体表的微生物进行测序将帮助我们了解这一机制。针对不同类群的嗅觉基因、嗅觉受体和配体的研究依然缺乏; 相应的功能基因的测序、基因表达实验和功能实验或许能找出嗅觉信号的产生以及和特定功能相关的通路。最后, 大脑多个区域的神经活动将转化为激素水平波动, 引发相应的生理和行为变化——而我们对这些神经通路仍知之甚少。

图2

图2

鸟类嗅觉通讯的研究框架。通路中的文字和箭头代表嗅觉相关因子及其传递方向(虚线代表未有确切证据的潜在关联); 5个方框代表本文提出的5个层面划分。

Fig. 2

The research framework of olfactory communication in birds. The black text and arrows represent olfactory-related factors and their transmission directions (dashed lines represent potential associations for which there is no conclusive evidence); the five boxes represent the five levels of division proposed in this review.

随着研究手段的不断创新, 多层次、全链条的鸟类嗅觉通讯研究是解决一系列问题的关键。通过整合多组学技术、解剖与生理学、行为学和神经生物学等手段, 我们更有可能全方位、精确地了解鸟类嗅觉通讯的机制(图2)。多层面的整合型研究需要以大量的数据和实验作为基础, 具有较高的难度; 对模式物种的研究或许是揭示相关机制的优先选择。在相关技术手段成熟的前提下, 非模式物种将为我们提供更为开阔和全面的视角。

值得注意的是, 整合鸟类多种感官系统的通讯研究也具有非常可观的潜力。比如, 鸟类如何在不同的线索和不同的感官之间进行权衡? 羽色、鸣声和气味, 或者说视觉、听觉和嗅觉, 三者之间是否存在一定形式的交互作用, 比如抑制、增强或者互补? 作为一个功能整体, 鸟类如何协调自己发出的信号以及接收信号的感官, 并将其在交流当中的效果最大化? 这些问题的解决将有助于我们明晰鸟类如何运用不同感官来感知刺激(Caro et al, 2015)。

参考文献

Avian olfaction: A review of the recent literature

Sex recognition by odour and variation in the uropygial gland secretion in starlings

Male quality and conspecific scent preferences in the house finch

Are female starlings able to recognize the scent of their offspring?

Why are female birds ornamented?

Account of the habits of the Turkey buzzard, Vultur aura, particularly with the view of exploding the opinion generally entertained of its extraordinary power of smelling

Pheromones are involved in the control of sexual behaviour in birds

Functional anatomy of the olfactory system in 23 orders of birds

Hybrid speciation leads to novel male secondary sexual ornamentation of an Amazonian bird

Self-odour recognition in European storm-petrel chicks

Olfactory sex recognition investigated in Antarctic prions

Evidence for nest-odour recognition in two species of diving petrel

In nearly every procellariiform species, the sense of smell appears to be highly adapted for foraging at sea, but the sense of smell among the diving petrels is enigmatic. These birds forage at considerable depth and are not attracted to odour cues at sea. However, several procellariiform species have recently been shown to relocate their nesting burrows by scent, suggesting that these birds use an olfactory signature to identify the home burrow. We wanted to know whether diving petrels use smell in this way. We tested the common diving petrel Pelecanoides urinatrix and the South-Georgian diving petrel Pelecanoides georgicus to determine whether diving petrels were able to recognise their burrow by scent alone. To verify the efficacy of the method, we also tested a bird that is known to use olfaction for foraging and nest recognition, the thin-billed prion Pachyptila belcheri. In two-choice T-maze trials, we found that, for all species, individuals significantly preferred the odour of their own nest material to that of a conspecific. Our findings strongly suggest that an individual-specific odour provides an olfactory signature that allows burrowing petrels to recognize their own burrow. Since this ability seems to be well developed in diving petrels, our data further implicate a novel adaptation for olfaction in these two species that have been presumed to lack a well-developed sense of smell.

Besides colours and songs, odour is the new black of avian communication

Partner-specific odor recognition in an Antarctic seabird

Among birds, the Procellariiform seabirds (petrels, albatrosses, and shearwaters) are prime candidates for using chemical cues for individual recognition. These birds have an excellent olfactory sense, and a variety of species nest in burrows that they can recognize by smell. However, the nature of the olfactory signature--the scent that makes one burrow smell more like home than another--has not been established for any species. Here, we explore the use of intraspecific chemical cues in burrow recognition and present evidence for partner-specific odor recognition in a bird.

Kin recognition and inbreeding avoidance in wild birds: The first evidence for individual kin-related odour recognition

Kin and nestmate recognition: The influence of W. D. Hamilton on 50 years of research

Potential semiochemical molecules from birds: A practical and comprehensive compilation of the last 20 years studies

The perfume of reproduction in birds: Chemosignaling in avian social life

DOI:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.06.001

PMID:24928570

[本文引用: 5]

This article is part of a Special Issue "Chemosignals and Reproduction". Chemical cues were probably the first cues ever used to communicate and are still ubiquitous among living organisms. Birds have long been considered an exception: it was believed that birds were anosmic and relied on their acute visual and acoustic capabilities. Birds are however excellent smellers and use odors in various contexts including food searching, orientation, and also breeding. Successful reproduction in most vertebrates involves the exchange of complex social signals between partners. The first evidence for a role of olfaction in reproductive contexts in birds only dates back to the seventies, when ducks were shown to require a functional sense of smell to express normal sexual behaviors. Nowadays, even if the interest for olfaction in birds has largely increased, the role that bodily odors play in reproduction still remains largely understudied. The few available studies suggest that olfaction is involved in many reproductive stages. Odors have been shown to influence the choice and synchronization of partners, the choice of nest-building material or the care for the eggs and offspring. How this chemical information is translated at the physiological level mostly remains to be described, although available evidence suggests that, as in mammals, key reproductive brain areas like the medial preoptic nucleus are activated by relevant olfactory signals. Olfaction in birds receives increasing attention and novel findings are continuously published, but many exciting discoveries are still ahead of us, and could make birds one of the animal classes with the largest panel of developed senses ever described. Copyright © 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Impact of kin odour on reproduction in zebra finches

Zebra finch chicks recognise parental scent, and retain chemosensory knowledge of their genetic mother, even after egg cross-fostering

Olfactory imprinting as a mechanism for nest odour recognition in zebra finches

Odour-based natal nest recognition in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata), a colony-breeding songbird

DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0775

PMID:20880859

[本文引用: 1]

Passerine birds have an extensive repertoire of olfactory receptor genes. However, the circumstances in which passerine birds use olfactory signals are poorly understood. The aim of this study is to investigate whether olfactory cues play a role in natal nest recognition in fledged juvenile passerines. The natal nest provides fledglings with a safe place for sleeping and parental food provisioning. There is a particular demand in colony-breeding birds for fledglings to be able to identify their nests because many pairs breed close to each other. Olfactory orientation might thus be of special importance for the fledglings, because they do not have a visual representation of the nest site and its position in the colony when leaving the nest for the first time. We investigated the role of olfaction in nest recognition in zebra finches, which breed in dense colonies of up to 50 pairs. We performed odour preference tests, in which we offered zebra finch fledglings their own natal nest odour versus foreign nest odour. Zebra finch fledglings significantly preferred their own natal nest odour, indicating that fledglings of a colony breeding songbird may use olfactory cues for nest recognition.

Intraspecific olfactory communication in zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata):Potential information apart from visual and acoustic cues

Why come back home? Investigating the proximate factors that influence natal philopatry in migratory passerines

Chemical kin label in seabirds

DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0340

PMID:21525047

[本文引用: 1]

Chemical signals yield critical socio-ecological information in many animals, such as species, identity, social status or sex, but have been poorly investigated in birds. Recent results showed that chemical signals are used to recognize their nest and partner by some petrel seabirds whose olfactory anatomy is well developed and which possess a life-history propitious to olfactory-mediated behaviours. Here, we investigate whether blue petrels (Halobaena caerulea) produce some chemical labels potentially involved in kin recognition and inbreeding avoidance. To overcome methodological constraints of chemical analysis and field behavioural experiments, we used an indirect behavioural approach, based on mice olfactory abilities in discriminating odours. We showed that mice (i) can detect odour differences between individual petrels, (ii) perceive a high odour similarity between a chick and its parents, and (iii) perceive this similarity only before fledging but not during the nestling developmental stage. Our results confirm the existence of an individual olfactory signature in blue petrels and show for the first time, to our knowledge, that birds may exhibit an olfactory kin label, which may have strong implications for inbreeding avoidance.

Wax, sex and the origin of species: Dual roles of insect cuticular hydrocarbons in adaptation and mating

DOI:10.1002/bies.201500014

PMID:25988392

[本文引用: 1]

Evolutionary changes in traits that affect both ecological divergence and mating signals could lead to reproductive isolation and the formation of new species. Insect cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) are potential examples of such dual traits. They form a waxy layer on the cuticle of the insect to maintain water balance and prevent desiccation, while also acting as signaling molecules in mate recognition and chemical communication. Because the synthesis of these hydrocarbons in insect oenocytes occurs through a common biochemical pathway, natural or sexual selection on one role may affect the other. In this review, we explore how ecological divergence in insect CHCs can lead to divergence in mating signals and reproductive isolation. We suggest that the evolution of insect CHCs may be ripe models for understanding ecological speciation. © 2015 The Authors. Bioessays published by WILEY Periodicals, Inc.

Odor-based recognition of familiar and related conspecifics: A first test conducted on captive Humboldt penguins (Spheniscus humboldti)

Diversity in olfactory bulb size in birds reflects allometry, ecology, and phylogeny

DOI:10.3389/fnana.2015.00102

PMID:26283931

[本文引用: 2]

The relative size of olfactory bulbs (OBs) is correlated with olfactory capabilities across vertebrates and is widely used to assess the relative importance of olfaction to a species' ecology. In birds, variations in the relative size of OBs are correlated with some behaviors; however, the factors that have led to the high level of diversity seen in OB sizes across birds are still not well understood. In this study, we use the relative size of OBs as a neuroanatomical proxy for olfactory capabilities in 135 species of birds, representing 21 orders. We examine the scaling of OBs with brain size across avian orders, determine likely ancestral states and test for correlations between OB sizes and habitat, ecology, and behavior. The size of avian OBs varied with the size of the brain and this allometric relationship was for the most part isometric, although species did deviate from this trend. Large OBs were characteristic of more basal species and in more recently derived species the OBs were small. Living and foraging in a semiaquatic environment was the strongest variable driving the evolution of large OBs in birds; olfaction may provide cues for navigation and foraging in this otherwise featureless environment. Some of the diversity in OB sizes was also undoubtedly due to differences in migratory behavior, foraging strategies and social structure. In summary, relative OB size in birds reflect allometry, phylogeny and behavior in ways that parallel that of other vertebrate classes. This provides comparative evidence that supports recent experimental studies into avian olfaction and suggests that olfaction is an important sensory modality for all avian species.

Vocal recognition suggests premating isolation between lineages of a lekking hummingbird

Highly contiguous genomes improve the understanding of avian olfactory receptor repertoires

Can house sparrows recognize familiar or kin-related individuals by scent?

Forty years of olfactory navigation in birds

Homing pigeons only navigate in air with intact environmental odours: A test of the olfactory activation hypothesis with GPS data loggers

Only natural local odours allow homeward orientation in homing pigeons released at unfamiliar sites

Nestling odour modulates behavioural response in male, but not in female zebra finches

DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-80466-z

PMID:33436859

[本文引用: 1]

Studies investigating parent offspring recognition in birds led to the conclusion that offspring recognition is absent at the early nestling stage. Especially male songbirds were often assumed to be unable to discriminate between own and foreign offspring. However, olfactory offspring recognition in birds has not been taken into account as yet, probably because particularly songbirds have for a long time been assumed anosmic. This study aimed to test whether offspring might be recognised via smell. We presented zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) parents either the odour of their own or that of foreign nestlings and investigated whether the odour presentation resulted in a change in the number of head saccades, i.e. the rapid horizontal turning of the head, with which birds scan their environment and which can be used as a proxy of arousal. Our experiment indicates that male zebra finches, in contrast to females, differentiate between their own and foreign offspring based on odour cues, as indicated by a significant differences in the change of head saccadic movements between males receiving the own chick odour and males receiving the odour of a foreign chick. Thus, it provides behavioural evidence for olfactory offspring recognition in male zebra finches and also the existence of appropriate phenotypic odour cues of the offspring. The question why females do not show any sign of behavioural response remains open, but it might be likely that females use other signatures for offspring recognition.

Social odour activates the hippocampal formation in zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata)

DOI:S0166-4328(19)30100-7

PMID:30738914

[本文引用: 1]

Experiments from our research group have demonstrated that the olfactory sense of birds, which has been considered as unimportant for a long time, plays a prominent role as communication channel in social behaviour. Odour cues are used e.g. by zebra finch chicks to recognize the mother, by adult birds to distinguish their own eggs from others, or to recognize kin. While there is quite a lot of evidence for the importance of odour for social behaviour, it is not known as yet which brain areas may be involved in the processing of socially relevant odours. We therefore compared the brain activation pattern of zebra finch males exposed to their own offspring odour with that induced by a neutral odour stimulus. By measuring head saccade changes as behavioural reaction and using the expression of the immediate early gene product c-Fos as brain activity marker, we show here that the activation pattern, namely the activity difference between the left and the right hemisphere, of several hippocampal areas in zebra finch males is altered by the presentation of the odour of their own nestlings. In contrast, the nucleus taeniae of the amygdala (TnA) exhibits a tendency of a reduction of c-Fos activation in both hemispheres as a consequence of exposure to the nestling odour. We conclude that the hippocampus is involved in odour based processing of social information, while the role of TnA remains unclear.Copyright © 2019 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Female zebra finches smell their eggs

Behavioural responses of songbirds to preen oil odour cues of sex and species

Olfactory camouflage and communication in birds

Songbirds show odour-based discrimination of similarity and diversity at the major histocompatibility complex

Olfactory assessment of competitors to the nest site: An experiment on a passerine species

The role of uropygial gland on sexual behavior in domestic chicken Gallus gallus domesticus

Can song discriminate between Macgillivray’s and Mourning warblers in a narrow hybrid zone?

Differences in olfactory species recognition in the females of two Australian songbird species

Are olfactory cues involved in nest recognition in two social species of estrildid finches?

Olfactory kin recognition in a songbird

DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2011.1093

PMID:22219391

The ability to recognize close relatives in order to cooperate or to avoid inbreeding is widespread across all taxa. One accepted mechanism for kin recognition in birds is associative learning of visual or acoustic cues. However, how could individuals ever learn to recognize unfamiliar kin? Here, we provide the first evidence for a novel mechanism of kin recognition in birds. Zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) fledglings are able to distinguish between kin and non-kin based on olfactory cues alone. Since olfactory cues are likely to be genetically based, this finding establishes a neglected mechanism of kin recognition in birds, particularly in songbirds, with potentially far-reaching consequences for both kin selection and inbreeding avoidance.

Blue petrels recognize the odor of their egg

Preen secretions encode information on MHC similarity in certain sex-dyads in a monogamous seabird

DOI:10.1038/srep06920

PMID:25370306

[本文引用: 1]

Animals are known to select mates to maximize the genetic diversity of their offspring in order to achieve immunity against a broader range of pathogens. Although several bird species preferentially mate with partners that are dissimilar at the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), it remains unknown whether they can use olfactory cues to assess MHC similarity with potential partners. Here we combined gas chromatography data with genetic similarity indices based on MHC to test whether similarity in preen secretion chemicals correlated with MHC relatedness in the black-legged kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla), a species that preferentially mates with genetically dissimilar partners. We found that similarity in preen secretion chemicals was positively correlated with MHC relatedness in male-male and male-female dyads. This study provides the first evidence that preen secretion chemicals can encode information on MHC relatedness and suggests that odor-based mechanisms of MHC-related mate choice may occur in birds.

Pigeons home faster through polluted air

DOI:10.1038/srep18989

PMID:26728113

[本文引用: 2]

Air pollution, especially haze pollution, is creating health issues for both humans and other animals. However, remarkably little is known about how animals behaviourally respond to air pollution. We used multiple linear regression to analyse 415 pigeon races in the North China Plain, an area with considerable air pollution, and found that while the proportion of pigeons successfully homed was not influenced by air pollution, pigeons homed faster when the air was especially polluted. Our results may be explained by an enhanced homing motivation and possibly an enriched olfactory environment that facilitates homing. Our study provides a unique example of animals' response to haze pollution; future studies are needed to identify proposed mechanisms underlying this effect.

Insectivorous birds can see and smell systemically herbivore-induced pines

DOI:10.1002/ece3.6622

PMID:32953066

[本文引用: 2]

Several studies have shown that insectivorous birds are attracted to herbivore-damaged trees even when they cannot see or smell the actual herbivores or their feces. However, it often remained an open question whether birds are attracted by herbivore-induced changes in leaf odor or in leaf light reflectance or by both types of changes. Our study addressed this question by investigating the response of great tits () and blue tits () to Scots pine () damaged by pine sawfly larvae (). We released the birds individually to a study booth, where they were simultaneously offered a systemically herbivore-induced and a noninfested control pine branch. In the first experiment, the birds could see the branches, but could not smell them, because each branch was kept inside a transparent, airtight cylinder. In the second experiment, the birds could smell the branches, but could not see them, because each branch was placed inside a nontransparent cylinder with a mesh lid. The results show that the birds were more attracted to the herbivore-induced branch in both experiments. Hence, either type of the tested cues, the herbivore-induced visual plant cue alone as well as the olfactory cues per se, is attractive to the birds.© 2020 The Authors. Ecology and Evolution published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Olfactory communication via microbiota: What is known in birds?

Atypical homing or self-odour avoidance?

Conspecific attraction and nest site selection in a nomadic species, the zebra finch

Blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) respond to an experimental change in the aromatic plant odour composition of their nest

DOI:10.1016/j.beproc.2008.07.003

PMID:18692552

[本文引用: 1]

Although the use of olfaction by birds is now widely recognised, the olfactory abilities of passerine birds remain poorly explored, for historical reasons. Several studies however suggest that passerines can perceive volatile compounds in several biologically relevant contexts. In Corsica, recent findings suggest that cavity-nesting blue tits may use volatile compounds in the context of nest building and maintenance. Although they build their nests mainly from moss, female blue tits also frequently incorporate fragments of several species of aromatic plants in the nest cup. In field experiments, breeding female blue tits altered their nest maintenance behaviour in response to experimental addition of aromatic plants in their nest. In aviary experiments, captive male blue tits could be trained to detect lavender odour from a distance. Here I report results from a field study aimed to test whether adult blue tits altered their chick-feeding behaviour after an experimental change in nest odour composition. I experimentally added fragments of aromatic plant species that differed from those brought in the nests before the start of the experiment in a set of experimental nests and added moss, the basic nest material, in a set of control nests. Both male and female blue tits hesitated significantly longer entering the nest cavity after addition of new aromatic plant fragments, as compared to moss addition. This response was especially observed during the first visit following the experimental change in nest plant composition. Nest composition treatment had no effect on the time spent in the nest. This study demonstrates that free-ranging blue tits detect changes in nest odour from outside the nest cavity.

Odour-based discrimination of subspecies, species and sexes in an avian species complex, the crimson rosella

Strong, but incomplete, mate choice discrimination between two closely related species of paper wasp

Magnetoreception and its trigeminal mediation in the homing pigeon

Preen oil and bird fitness: A critical review of the evidence

The Chemistry of Avian Odors: An Introduction to Best Practices

Giant panda scent-marking strategies in the wild: Role of season, sex and marking surface

Of volatiles and peptides: In search for MHC-dependent olfactory signals in social communication

DOI:10.1007/s00018-014-1559-6

PMID:24496643

[本文引用: 1]

Genes of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which play a critical role in immune recognition, are considered to influence social behaviors in mice, fish, humans, and other vertebrates via olfactory cues. As studied most extensively in mice, the polymorphism of MHC class I genes is considered to bring about a specific scent signature, which is decoded by the olfactory system resulting in an individual-specific reaction such as mating. On the assumption that this signature resides in volatiles, extensive attempts to identify these MHC-specific components in urine failed. Alternatively, it has been suggested that peptide ligands of MHC class I molecules are released into urine and can elicit an MHC-haplotype-specific behavioral response after uptake into the nose by sniffing. Analysis of the urinary peptide composition of mice shows that MHC-derived peptides are present, albeit in extremely low concentrations. In contrast, urine contains abundant peptides which differ between mouse strains due to genomic variations such as single-nucleotide variations or complex polymorphisms in multigene families as well as in their concentration. Thus, urinary peptides represent a real-time sampling of the expressed genome available for sensory evaluation. It is suggested that peptide variation caused by genomic differences contains sufficient information for individual recognition beyond or instead of an influence of the MHC in mice and other vertebrates.

Olfaction and homing in pigeons

Olfaction: Anatomy, physiology, and disease

DOI:10.1002/ca.22338

PMID:24272785

[本文引用: 1]

The olfactory system is an essential part of human physiology, with a rich evolutionary history. Although humans are less dependent on chemosensory input than are other mammals (Niimura 2009, Hum. Genomics 4:107-118), olfactory function still plays a critical role in health and behavior. The detection of hazards in the environment, generating feelings of pleasure, promoting adequate nutrition, influencing sexuality, and maintenance of mood are described roles of the olfactory system, while other novel functions are being elucidated. A growing body of evidence has implicated a role for olfaction in such diverse physiologic processes as kin recognition and mating (Jacob et al. 2002a, Nat. Genet. 30:175-179; Horth 2007, Genomics 90:159-175; Havlicek and Roberts 2009, Psychoneuroendocrinology 34:497-512), pheromone detection (Jacob et al. 200b, Horm. Behav. 42:274-283; Wyart et al. 2007, J. Neurosci. 27:1261-1265), mother-infant bonding (Doucet et al. 2009, PLoS One 4:e7579), food preferences (Mennella et al. 2001, Pediatrics 107:E88), central nervous system physiology (Welge-Lüssen 2009, B-ENT 5:129-132), and even longevity (Murphy 2009, JAMA 288:2307-2312). The olfactory system, although phylogenetically ancient, has historically received less attention than other special senses, perhaps due to challenges related to its study in humans. In this article, we review the anatomic pathways of olfaction, from peripheral nasal airflow leading to odorant detection, to epithelial recognition of these odorants and related signal transduction, and finally to central processing. Olfactory dysfunction, which can be defined as conductive, sensorineural, or central (typically related to neurodegenerative disorders), is a clinically significant problem, with a high burden on quality of life that is likely to grow in prevalence due to demographic shifts and increased environmental exposures.Copyright © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Speciation rates are correlated with changes in plumage color complexity in the largest family of songbirds

DOI:10.1111/evo.13982

PMID:32333393

[本文引用: 1]

Although evolutionary theory predicts an association between the evolution of elaborate ornamentation and speciation, empirical evidence for links between speciation and ornament evolution has been mixed. In birds, the evolution of increasingly complex and colorful plumage may promote speciation by introducing prezygotic mating barriers. However, overall changes in color complexity, including both increases and decreases, may also promote speciation by altering the sexual signals that mediate reproductive choices. Here, we examine the relationship between complex plumage and speciation rates in the largest family of songbirds, the tanagers (Thraupidae). First, we test whether species with more complex plumage coloration are associated with higher speciation rates and find no correlation. We then test whether rates of male or female plumage color complexity evolution are correlated with speciation rates. We find that elevated rates of plumage complexity evolution are associated with higher speciation rates, regardless of sex and whether species are evolving more complex or less complex ornamentation. These results extend to whole-plumage color complexity and regions important in signaling (crown and throat) but not nonsignaling regions (back and wingtip). Our results suggest that the extent of change in plumage traits, rather than overall values of plumage complexity, may play a role in speciation.© 2020 The Authors. Evolution © 2020 The Society for the Study of Evolution.

Extra-pair mating in a passerine bird with highly duplicated major histocompatibility complex class II: Preference for the golden mean

DOI:10.1111/mec.15273

PMID:31614034

[本文引用: 1]

Genes of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) are essential in vertebrate adaptive immunity, and they are highly diverse and duplicated in many lineages. While it is widely established that pathogen-mediated selection maintains MHC diversity through balancing selection, the role of mate choice in shaping MHC diversity is debated. Here, we investigate female mating preferences for MHC class II (MHCII) in the bluethroat (Luscinia svecica), a passerine bird with high levels of extra-pair paternity and extremely duplicated MHCII. We genotyped family samples with mixed brood paternity and categorized their MHCII alleles according to their functional properties in peptide binding. Our results strongly indicate that females select extra-pair males in a nonrandom, self-matching manner that provides offspring with an allelic repertoire size closer to the population mean, as compared to offspring sired by the social male. This is consistent with a compatible genes model for extra-pair mate choice where the optimal allelic diversity is intermediate, not maximal. This golden mean presumably reflects a trade-off between maximizing pathogen recognition benefits and minimizing autoimmunity costs. Our study exemplifies how mate choice can reduce the population variance in individual MHC diversity and exert strong stabilizing selection on the trait. It also supports the hypothesis that extra-pair mating is adaptive through altered genetic constitution in offspring.© 2019 The Authors. Molecular Ecology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Begging blue tit nestlings discriminate between the odour of familiar and unfamiliar conspecifics

Female mating preferences and offspring survival: Testing hypotheses on the genetic basis of mate choice in a wild lekking bird

DOI:10.1111/mec.12652

PMID:24383885

[本文引用: 1]

Indirect benefits of mate choice result from increased offspring genetic quality and may be important drivers of female behaviour. 'Good-genes-for-viability' models predict that females prefer mates of high additive genetic value, such that offspring survival should correlate with male attractiveness. Mate choice may also vary with genetic diversity (e.g. heterozygosity) or compatibility (e.g. relatedness), where the female's genotype influences choice. The relative importance of these nonexclusive hypotheses remains unclear. Leks offer an excellent opportunity to test their predictions, because lekking males provide no material benefits and choice is relatively unconstrained by social limitations. Using 12 years of data on lekking lance-tailed manakins, Chiroxiphia lanceolata, we tested whether offspring survival correlated with patterns of mate choice. Offspring recruitment weakly increased with father attractiveness (measured as reproductive success, RS), suggesting attractive males provide, if anything, only minor benefits via offspring viability. Both male RS and offspring survival until fledging increased with male heterozygosity. However, despite parent-offspring correlation in heterozygosity, offspring survival was unrelated to its own or maternal heterozygosity or to parental relatedness, suggesting survival was not enhanced by heterozygosity per se. Instead, offspring survival benefits may reflect inheritance of specific alleles or nongenetic effects. Although inbreeding depression in male RS should select for inbreeding avoidance, mates were not less related than expected under random mating. Although mate heterozygosity and relatedness were correlated, selection on mate choice for heterozygosity appeared stronger than that for relatedness and may be the primary mechanism maintaining genetic variation in this system despite directional sexual selection. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Kin recognition by juvenile predatory mites: Prior association or phenotype matching?

Volatile and semivolatile compounds in gray catbird uropygial secretions vary with age and between breeding and wintering grounds

DOI:10.1007/s10886-011-9931-6

PMID:21424249

[本文引用: 2]

The uropygial secretions of some bird species contain volatile and semivolatile compounds that are hypothesized to serve as chemical signals. The abundance of secretion components varies with age and season, although these effects have not been investigated in many species. We used solid-phase microextraction headspace sampling and solvent extraction coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to detect and identify volatile and semivolatile chemical compounds in uropygial secretions of gray catbirds (Dumetella carolinensis). We identified linear and branched saturated carboxylic acids from acetic (C2) through hexacosanoic (C26); linear alcohols from decanol (C10) through docosanol (C22); one aromatic aldehyde; one monounsaturated carboxylic acid; two methyl ketones; and a C28 ester. We tested for the effect of age on signal strength and found that juvenile birds produced greater amounts of volatile C4 through C7 acids and semivolatile C20 through C26 acids, although the variation among individuals was large. Adult birds displayed small concentrations and minimal individual variation among volatile compounds, but produced significantly higher levels of long-chain linear alcohols than juvenile birds. We tested for the effects of season/location by sampling adult catbirds at their Ohio breeding grounds and at their Florida wintering grounds and found that the heaviest carboxylic acids are significantly more abundant in secretions from birds sampled during winter at the Florida site, whereas methyl ketones are more abundant in birds sampled during summer on the Ohio breeding grounds. We observed no effect of sex on semivolatile compounds, but we found a significant effect of sex on levels of carboxylic acids (C4 through C7) for juvenile birds only.

Avian olfactory receptor gene repertoires:Evidence for a well-developed sense of smell in birds?

Variation in preen oil composition pertaining to season, sex, and genotype in the polymorphic white-throated sparrow

DOI:10.1007/s10886-014-0493-2

PMID:25236380

[本文引用: 2]

Evidence for the the ability of birds to detect olfactory signals is now well documented, yet it remains unclear whether birds secrete chemicals that can be used as social cues. A potential source of chemical cues in birds is the secretion from the uropygial gland, or preen gland, which is thought to waterproof, maintain, and protect feathers from ectoparasites. However, it is possible that preen oil also may be used for individual recognition, mate choice, and signalling social/sexual status. If preen oil secretions can be used as socio-olfactory signals, we should be able to identify the volatile components that could make the secretions more detectable, determine the seasonality of these secretions, and determine whether olfactory signals differ among relevant social groups. We examined the seasonal differences in volatile compounds of the preen oil of captive white-throated sparrows, Zonotrichia albicollis. This species is polymorphic and has genetically determined morphs that occur in both sexes. Mating is almost exclusively disassortative with respect to morph, suggesting strong mate choice. By sampling the preen oil from captive birds in breeding and non-breeding conditions, we identified candidate chemical signals that varied according to season, sex, morph, and species. Linear alcohols with a 10-18 carbon chains, as well as methyl ketones and carboxylic acids, were the most abundant volatile compounds. Both the variety and abundances of some of these compounds were different between the sexes and morphs, with one morph secreting more volatile compounds in the non-breeding season than the other. In addition, 12 compounds were seasonally elevated in amount, and were secreted in high amounts in males. Finally, we found that preen oil signatures tended to be species-specific, with white-throated sparrows differing from the closely related Junco in the abundances and/or prevalence of at least three compounds. Our data suggest roles for preen oil secretions and avian olfaction in both non-social as well as social interactions.

Conspecific olfactory preferences and interspecific divergence in odor cues in a chickadee hybrid zone

DOI:10.1002/ece3.5497

[本文引用: 2]

Understanding how mating cues promote reproductive isolation upon secondary contact is important in describing the speciation process in animals. Divergent chemical cues have been shown to act in reproductive isolation across many animal taxa. However, such cues have been overlooked in avian speciation, particularly in passerines, in favor of more traditional signals such as song and plumage. Here, we aim to test the potential for odor to act as a mate choice cue, and therefore contribute to premating reproductive isolation between the black-capped (Poecile atricapillus) and Carolina chickadee (P. carolinensis) in eastern Pennsylvania hybrid zone populations. Using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, we document significant species differences in uropygial gland oil chemistry, especially in the ratio of ester to nonester compounds. We also show significant preferences for conspecific over heterospecific odor cues in wild chickadees using a Y-maze design. Our results suggest that odor may be an overlooked but important mating cue in these chickadees, potentially promoting premating reproductive isolation. We further discuss several promising avenues for future research in songbird olfactory communication and speciation.

Further aviary experiments with homing pigeons: Probable influence of dynamic factors of the atmosphere on their orientation

Bird odour predicts reproductive success

Female-based patterns and social function in avian chemical communication

DOI:10.1007/s10886-020-01230-1

PMID:33103230

[本文引用: 3]

Much of the growing interest in avian chemical signals has focused on the role of kin recognition or mate attraction, often with an emphasis on males, with uropygial gland secretions perhaps providing information about an individual's identity and quality. Yet, data collected to date suggest sexual dimorphism in uropygial glands and secretions are often emphasized in female, rather than in male birds. That is, when a sexual difference occurs (often during the breeding season only), it is the female that typically exhibits one of three patterns: (1) a larger uropygial gland, (2) a greater abundance of volatile or semi-volatile preen oil compounds and/or (3) greater diversity of preen oil compounds or associated microbes. These patterns fit a majority of birds studied to date (23 of 30 chemically dimorphic species exhibit a female emphasis). Multiple species that do not fit are confounded by a lack of data for seasonal effects or proper quantitative measures of chemical compounds. We propose several social functions for these secretions in female-based patterns, similar to those reported in mammals, but which are largely unstudied in birds. These include: (1) intersexual advertisement of female receptivity or quality, including priming effects on male physiology, (2) intrasexual competition, including scent marking and reproductive suppression or (3) parental behaviors, such as parent-offspring recognition and chemical protection of eggs and nestlings. Revisiting the gaps of chemical studies to quantify the existence of female social chemosignals and any fitness benefit(s) during breeding are potentially fruitful but overlooked areas of future research.

Chemical profiles reflect heterozygosity and seasonality in a tropical lekking passerine bird

Behavioral responses of nesting female dark-eyed juncos Junco hyemalis to hetero- and conspecific passerine preen oils

Intraspecific preen oil odor preferences in dark-eyed juncos

(Junco hyemalis).

Patterns of MHC-dependent mate selection in humans and nonhuman primates: A meta-analysis

DOI:10.1111/mec.13920

PMID:27859823

[本文引用: 2]

Genes of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in vertebrates are integral for effective adaptive immune response and are associated with sexual selection. Evidence from a range of vertebrates supports MHC-based preference for diverse and dissimilar mating partners, but evidence from human mate choice studies has been disparate and controversial. Methodologies and sampling peculiarities specific to human studies make it difficult to know whether wide discrepancies in results among human populations are real or artefact. To better understand what processes may affect MHC-mediated mate choice across humans and nonhuman primates, we performed phylogenetically controlled meta-analyses using 58 effect sizes from 30 studies across seven primate species. Primates showed a general trend favouring more MHC-diverse mates, which was statistically significant for humans. In contrast, there was no tendency for MHC-dissimilar mate choice, and for humans, we observed effect sizes indicating selection of both MHC-dissimilar and MHC-similar mates. Focusing on MHC-similar effect sizes only, we found evidence that preference for MHC similarity was an artefact of population ethnic heterogeneity in observational studies but not among experimental studies with more control over sociocultural biases. This suggests that human assortative mating biases may be responsible for some patterns of MHC-based mate choice. Additionally, the overall effect sizes of primate MHC-based mating preferences are relatively weak (Fisher's Z correlation coefficient for dissimilarity Zr = 0.044, diversity Zr = 0.153), calling for careful sampling design in future studies. Overall, our results indicate that preference for more MHC-diverse mates is significant for humans and likely conserved across primates.© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Effects of air pollution on individual performance in homing pigeon

空气污染对信鸽比赛个体归巢速度的影响

Uropygial gland volatiles may code for olfactory information about sex, individual, and species in Bengalese finches Lonchura striata

Uropygial gland-secreted alkanols contribute to olfactory sex signals in budgerigars

Uropygial gland volatiles facilitate species recognition between two sympatric sibling bird species