1 背景

物种多样性及其状态已成为全球公认的评估可持续发展的关键指标(Mittermeier et al, 1998; Brooks et al, 2006; Tilman et al, 2017)。在人类活动日益成为全球环境变化的主导因素的背景下, 生物多样性的全球指标使得国际各方机构可以追踪可持续发展的进程(Pereira & Cooper, 2006; Lohbeck et al, 2016; Proença et al, 2017)。在全球尺度, 生物多样性的度量指标是评估爱知生物多样性目标(Aichi Biodiversity Targets)和联合国可持续发展目标(UN sustainable development goals)是否实现的主要指标(O’Connor et al, 2015)。在区域尺度, 保护和维持物种多样性以提供人类生计与情感愉悦所需是保护地的重要实用功能(Naughton-Treves et al, 2005)。生物多样性监测是保护地用以评估其资源状况及其保护能力的手段。关键物种的变化动态是保护地评估其管理行动, 尤其是保护行动, 是否有效的重要衡量标准(Li et al, 2012; Wetzel et al, 2015)。

传统的调查物种数量及其分布的方法以凭证标本(voucher specimen)为依据, 记录下于何时、何地采集到某物种, 以及其他的辅助信息, 例如采集方式、采集人等。这些凭证标本和附属信息构成了全世界博物馆的核心数据, 并提供了全球生物多样性的重要基准信息(Suarez & Tsutsui, 2004; Edwards, 2004)。然而, 在全球气候变化和人类活动对生态系统影响快速扩张的当下, 生物多样性的测量如何跟上环境变化的速度就至关重要, 这样才能保证管理决策者能够依据当下最新的数据, 及时快速地制定政策与管理对策(Visconti et al, 2016; Santini et al, 2017; Kays et al, 2020)。科学技术的发展正在日益满足这个领域的需求。比如, 遥感技术的发展已经为追踪土地利用变化、监测火灾、评估森林破碎化和植物生产力变化提供了极好的工具(O’Connor et al, 2015; Skidmore et al, 2015)。但是, 对于那些分布和生存依赖于具体栖息地特征(而不仅仅是栖息地类型)的物种, 卫星或机载传感器通常难以监测到此类动物群落的变化; 栖息地的变化(或稳定)并不能够反映出由疾病、偷猎或外来物种入侵等原因引起的野生动物种群的变化(Pereira & Cooper, 2006; Steenweg et al, 2017)。对于重要的野生动物物种, 需要建立快速收集和处理数据的同时对被监测物种干扰小、能准确反映其多度和分布变化的监测体系(Rowcliffe & Carbone, 2008)。如果建立起社会公众可以通过数据收集而参与其中的机制, 生物多样性监测也可以从中受益(McShea et al, 2016; Forrester et al, 2017)。

红外相机技术是可以有效探测许多大中型野生动物(例如有蹄类、食肉类、部分灵长类)的技术体系, 已经过广泛的测试和应用; 对于准确监测不同目标物种类群所需的取样方法和取样量, 以及在做数据对比时需要哪些元数据作为基础, 已经有研究者进行了系统的了解与评估(O’Connell et al, 2010; Meek et al, 2014; Kays et al, 2020)。红外相机照片所附属的信息是至关重要的; 一份影像(image, 照片或视频)只有在包含诸如物种名称、拍摄地点、拍摄日期(和时间)、相机型号和采集人等信息时, 才算成为有效的记录(数字化标本) (Forrester et al, 2016); 这些信息就是红外相机照片的元数据, 必须在数据库中通过唯一编号(unique ID)与照片相关联。同时还有其他与相机设置位点有关的协变量(比如探测距离、植被特征、天气状况等), 这些变量可以用来解释调查位点之间的差异(O’Connell et al, 2010; Meek et al, 2014)。单个调查位点上的所有记录都与这样一组协变量对应, 从而可以解释为什么在某些位点和时间段里记录了更多物种, 以及为什么同一物种在不同位点上的探测率和多度会有所不同。如果在一个数据库中整合多个调查项目, 就会需要更多的字段信息, 比如, 调查是否使用了诱饵或气味剂、相机阵列的空间布设方案等。因此, 我们需要对红外相机布设所用的规程进行规范, 同时严格规定对照片关联信息设定统一的数据格式标准, 即元数据结构(Forrester et al, 2016; McShea et al, 2016; Ahumada et al, 2020)。这样标准化的元数据结构不仅对于单个项目或研究组来说是重要的, 同时也是不同机构、部门和国家之间共享数据的必需基础(Ahumada et al, 2020)。我们认为, 对许多物种来说, 红外相机影像是一套更为有效的凭证系统, 而这一系统的推广应用, 需要建立起标准化的元数据结构和管理框架。

2 中国红外相机发展现状

红外相机技术在20世纪90年代被引入中国, 随着方法的日渐成熟, 在过去25年里被大规模地用于野生动物的监测和研究(李晟等, 2014; 朱淑怡等, 2017; 肖治术, 2019)。中国大多数的国家级自然保护区内均布设了红外相机用于野生动物调查和评估。中国的科研院所和高校建立了一系列以红外相机技术为核心的监测网络, 其中调查规模较大和调查持续时间较长的平台包括: 生态环境部南京环境科学研究所组织建立的全国哺乳动物多样性观测网络(China BON-Mammal; 李佳琦等, 2018)、中国科学院动物研究所牵头建立的中国生物多样性监测与研究网络中的兽类监测网(Sino BON-Mammal; 肖治术等, 2014, 2017,

中国现有的红外相机监测项目极大地促进了大型兽类的调查研究以及对其种群趋势的监测, 从而为保护行动提供了有效支持。研究人员也正在开发基于红外相机影像自动识别、鉴定物种的工具, 并将这些工具整合入红外相机影像数据库, 以快速处理野外拍摄的大量影像。部分数据库还包括数据分析(例如计算物种相对多度指数、分析物种日活动节律、绘制物种累积曲线等)与生成报表的工具。中国大部分的红外相机调查采用了网格化的布设方案(例如1 km × 1 km, 2 km × 2 km, 3.6 km × 3.6 km等), 数据库的基本数据格式相似, 这使得将来不同监测平台之间开展数据共享在技术上是可行的。

剩下的问题是如何调动大家在不同平台之间开展数据共享的意愿, 同时确保数据共享中的公平。根据监测目标的不同, 不同监测项目的取样样本量大小与调查时长之间可能存在差别, 但都需要达到最基本的要求(如, 采用网格化的布设方案, 调查时长不少于30天)。数据共享的关键在于野生动物影像与关联数据的数据格式标准。这些数据可以用于两个目的: (1)为完成单个研究区域内的研究或监测提供所需的数据; (2)为大尺度(比如国家、洲或全球)评估提供生物多样性度量指标(Ahumada et al, 2020)。后者并不是大多数使用红外相机的研究者或管理者所考虑的首要目标, 但对监测大尺度生物多样性的研究人员而言却很重要(Jetz et al, 2012)。所以数据共享的挑战在于如何兼顾局域和大尺度的监测需求, 既能满足局域的研究和管理人员调查的需求, 也可以为大尺度的研究提供可访问的数据。由于中国幅员辽阔, 任何一个单位和组织的工作都不足以描述中国大中型兽类多样性的全貌, 因此, 面向国家层级未来的保护规划需求, 开展数据分享将是大势所趋。

3 数据共享的标准与政策

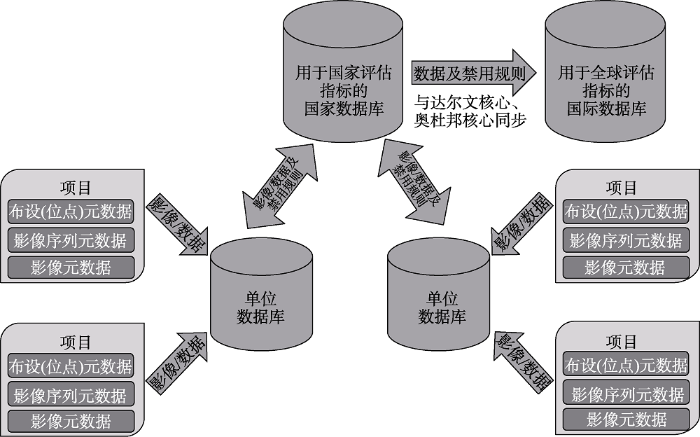

目前, 有多种软件可以用于标记图片和管理各个层级的信息, 比如Digikam、Adobe Bridge和Adobe Lightroom。机构或个人可以使用这些软件来对他们的野生动物照片进行归类与管理。近年来快速发展的人工智能(AI)技术将具备自动识别空拍照片并最终自动鉴定物种的能力, 加快数据处理的速度(Norouzzadeh et al, 2018; Thau et al, 2019)。但是, 在提供信息下载和数据格式转化等简单的功能之外, 对于用户来说, 这些软件现有的功能并不能满足跨平台数据共享的需求。这些软件现有的简单数据格式转换功能不能在统一数据格式的过程中实现不同数据集间的数据语言和格式的匹配。数据共享首先需要建立在共同的语言和数据标准之上, 我们推荐参考Forrester等(2016)提出的可共享的红外相机数据标准。在该标准中, 每份影像都需要被赋予一个独立的编号, 单次触发连续拍摄的一组影像合并为一个序列(sequence); 当不同动物物种或个体在相机传感器前移动时, 单台相机在一次布设(deployment)中就拍摄到一系列的影像序列; 这些布设组合起来就构成了子项目(sub-project)或者项目(project)。由此构建出一个多级管理结构的数据库(图1), 其中每一个层级的数据都建立有相应的标准化元数据结构, 便于数据管理者和使用者对数据进行检索和分类管理(McShea et al, 2016; Ahumada et al, 2020)。这样的数据标准包含必需的字段, 例如项目编号、相机位点编号、鉴定人、相机布设日期、相机收回日期、影像拍摄日期与时间、拍摄物种、个体数量、相机型号等。其他的附属数据(例如温度、是否使用诱饵/引诱剂、栖息地类型等)也是很有价值的信息, 但并非必需。我们强烈建议中国目前正在使用红外相机的机构和组织, 在数据存储过程中采用最基本的数据标准, 为将来的数据共享做好前期准备。

图1

图1

红外相机元数据结构及单位数据库与国家、国际数据库间数据交换的数据流架构示意图

Fig. 1

A common camera-trapping metadata structure and schema for data flow between institutional repositories and national and international repositories

目前, 有一些包含数据共享与禁用(embargo)政策的国际红外相机数据平台已经建成。这些国际数据平台的构建与运行基于如下的假设, 即数据共享可以增加样本量, 拓宽每个野生动物物种数据的时空范围, 进而可以优化这些物种的分析模型和度量指标(Jetz et al, 2012)。单项研究所能获得的目标物种的数据往往十分有限, 不足以构建可靠的模型, 但不同研究者开展的同类项目的整合就可以让这样的分析成为可能。例如, 一个专注于评估某种大型食肉动物种群密度的项目可能获得充足的资金支持, 这样的项目同时也能收集到大量非目标物种的“兼捕(by-catch)”数据, 类似这样的附加产出能够为那些研究不受关注物种的研究人员提供宝贵的数据。这类国际数据共享平台的例子包括: 由史密森学会(Smithsonian Institution)牵头建立的eMammal红外相机数据平台(

在中国, 研究者与政府部门普遍关心数据共享后是否会出现在共享协议规定范围之外被不当使用的问题; 这也是其他各类数据库共同关心的问题。ForestGEO森林动态样地网络(https://forestgeo.si.edu/)所采用的另一种数据共享模式可以作为参考。在该网络内, 单个森林样地遵循统一的野外调查规程和元数据结构开展样地调查, 获得的样地清查数据集汇总为一个总体数据库; 该数据库建有一个面向公众的网站, 集中展示每个样地数据集的概要描述。但是, 如果要获取具体某个数据集, 必须首先获得相应项目负责人的许可, 然后通过电子邮件链接进行数据分享。ForestGEO数据库中包括了多个中国样地的数据集, 在保证了数据标准与质量的同时也使得合作者之间可以进行数据共享。中国森林生物多样性监测网络(CForBio, www.cfbiodiv.org/)内发展出了一套独立的数据共享机制。在该网络内, 寻求合作与数据共享的研究者需要把研究方案发送给其他样地的负责人, 对拟议的研究问题、作者署名、数据需求等进行说明。同意参与的数据所有者将会从申请人那里获得用于数据分析的R代码, 对自己的数据进行分析, 然后把分析结果发送给申请人, 从而无需共享其原始数据。以上两个案例的实践均表明, 对数据发表公平性或敏感数据分享风险的担心, 并不妨碍大家建立起一套通用的数据标准。

4 对下一步工作的建议

保护生物多样性已成为全球共识与责任, 而这离不开国际合作(Proença et al, 2017; Steenweg et al, 2017; Kissling et al, 2018)。许多受关注的物种的分布范围跨越多个区域、国家或地区, 这些物种动态的任何度量指标的评估, 都依赖不同国家间及同一国家内不同机构和研究人员之间的合作(Ahumada et al, 2020)。我们需要建立跨越政治和行政边界的合作途径, 而这始于数据采集者之间的交流。我们建议分步骤地推进红外相机研究者之间的合作。首先, 创建论坛, 探讨全球尺度和国家内的监测需求。其次, 协调各方共同确定共享的元数据结构, 或至少确定每个独立数据集中必须包含的组成部分, 以及相应的数据字段, 共同建立各方均认可的监测标准与数据标准, 开发数据库之间的通用接口(APIs)。第三, 通过提供便利的数据上传和分析工具作为激励, 确保有更多数据加入这些大的数据平台。第四, 制定国内和合作国家之间数据共享的规则。每个国家都需要制定适用于其国内参与者的规则, 可以共享原始的或者处理后的数据, 可以将数据上传至全球数据库, 也可以在国家或者区域内建立独立的数据共享平台, 但最终的目标应该是确保不同的监测项目采用相同的元数据结构, 进而可以采用统一的方法和指标计算全球的度量指标, 以汇总评估全球可持续发展的进程, 以及监测跨界分布的物种。

全球自然保护的共同体需要中国的参与以准确评估全球可持续发展进程。作为参与的第一步, 中国的野生动物研究人员、机构之间需要首先实现数据共享, 然后再作为一个整体来决定如何与国际社会的保护工作者之间共享数据。只有通过这样的途径, 中国才能建立起定量评估其保护进展的指标体系, 使国际社会对中国丰富的生物多样性有更充分的认识。近20年来, 中国积极参与生物多样性监测与保护的国际事务, 在其中所发挥的作用和影响力日益增加。中国已经发起或开始主导建立数个国际生物多样性大数据平台, 例如, 中国政府近期刚刚宣布, 将设立“可持续发展大数据国际研究中心”, 为落实《联合国2030年可持续发展议程》提供新助力。统一的数据标准与共同的数据分享机制的建立, 将为这些国际数据平台的开发、建设提供必要的基础。

附录 Supplementary Material

参考文献

Wildlife Insights: A platform to maximize the potential of camera trap and other passive sensor wildlife data for the planet

Global biodiversity conservation priorities

DOI:10.1126/science.1127609

URL

PMID:16825561

[本文引用: 1]

The location of and threats to biodiversity are distributed unevenly, so prioritization is essential to minimize biodiversity loss. To address this need, biodiversity conservation organizations have proposed nine templates of global priorities over the past decade. Here, we review the concepts, methods, results, impacts, and challenges of these prioritizations of conservation practice within the theoretical irreplaceability/vulnerability framework of systematic conservation planning. Most of the templates prioritize highly irreplaceable regions; some are reactive (prioritizing high vulnerability), and others are proactive (prioritizing low vulnerability). We hope this synthesis improves understanding of these prioritization approaches and that it results in more efficient allocation of geographically flexible conservation funding.

Research and societal benefits of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility

DOI:10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0485:VAB]2.0.CO;2 URL [本文引用: 1]

Creating advocates for mammal conservation through citizen science

DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.06.025 URL [本文引用: 2]

An open standard for camera trap data

DOI:10.3897/BDJ.4.e10197 URL [本文引用: 3]

Integrating biodiversity distribution knowledge: Toward a global map of life

DOI:10.1016/j.tree.2011.09.007

URL

PMID:22019413

[本文引用: 2]

Global knowledge about the spatial distribution of species is orders of magnitude coarser in resolution than other geographically-structured environmental datasets such as topography or land cover. Yet such knowledge is crucial in deciphering ecological and evolutionary processes and in managing global change. In this review, we propose a conceptual and cyber-infrastructure framework for refining species distributional knowledge that is novel in its ability to mobilize and integrate diverse types of data such that their collective strengths overcome individual weaknesses. The ultimate aim is a public, online, quality-vetted 'Map of Life' that for every species integrates and visualizes available distributional knowledge, while also facilitating user feedback and dynamic biodiversity analyses. First milestones toward such an infrastructure have now been implemented.

An empirical evaluation of camera trap study design: How many, how long and when?

Building essential biodiversity variables (EBVs) of species distribution and abundance at a global scale

DOI:10.1111/brv.12359

URL

PMID:28766908

[本文引用: 1]

Much biodiversity data is collected worldwide, but it remains challenging to assemble the scattered knowledge for assessing biodiversity status and trends. The concept of Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs) was introduced to structure biodiversity monitoring globally, and to harmonize and standardize biodiversity data from disparate sources to capture a minimum set of critical variables required to study, report and manage biodiversity change. Here, we assess the challenges of a 'Big Data' approach to building global EBV data products across taxa and spatiotemporal scales, focusing on species distribution and abundance. The majority of currently available data on species distributions derives from incidentally reported observations or from surveys where presence-only or presence-absence data are sampled repeatedly with standardized protocols. Most abundance data come from opportunistic population counts or from population time series using standardized protocols (e.g. repeated surveys of the same population from single or multiple sites). Enormous complexity exists in integrating these heterogeneous, multi-source data sets across space, time, taxa and different sampling methods. Integration of such data into global EBV data products requires correcting biases introduced by imperfect detection and varying sampling effort, dealing with different spatial resolution and extents, harmonizing measurement units from different data sources or sampling methods, applying statistical tools and models for spatial inter- or extrapolation, and quantifying sources of uncertainty and errors in data and models. To support the development of EBVs by the Group on Earth Observations Biodiversity Observation Network (GEO BON), we identify 11 key workflow steps that will operationalize the process of building EBV data products within and across research infrastructures worldwide. These workflow steps take multiple sequential activities into account, including identification and aggregation of various raw data sources, data quality control, taxonomic name matching and statistical modelling of integrated data. We illustrate these steps with concrete examples from existing citizen science and professional monitoring projects, including eBird, the Tropical Ecology Assessment and Monitoring network, the Living Planet Index and the Baltic Sea zooplankton monitoring. The identified workflow steps are applicable to both terrestrial and aquatic systems and a broad range of spatial, temporal and taxonomic scales. They depend on clear, findable and accessible metadata, and we provide an overview of current data and metadata standards. Several challenges remain to be solved for building global EBV data products: (i) developing tools and models for combining heterogeneous, multi-source data sets and filling data gaps in geographic, temporal and taxonomic coverage, (ii) integrating emerging methods and technologies for data collection such as citizen science, sensor networks, DNA-based techniques and satellite remote sensing, (iii) solving major technical issues related to data product structure, data storage, execution of workflows and the production process/cycle as well as approaching technical interoperability among research infrastructures, (iv) allowing semantic interoperability by developing and adopting standards and tools for capturing consistent data and metadata, and (v) ensuring legal interoperability by endorsing open data or data that are free from restrictions on use, modification and sharing. Addressing these challenges is critical for biodiversity research and for assessing progress towards conservation policy targets and sustainable development goals.

Progress in construction of China Mammal Diversity Observation Network (China BON-Mammals)

全国哺乳动物多样性观测网络(China BON-Mammals)建设进展

Gauging the impact of management expertise on the distribution of large mammals across protected areas

Beyond pandas, the need for a standardized monitoring protocol for large mammals in Chinese nature reserves

Camera-trapping in wildlife research and conservation in China: Review and outlook

红外相机技术在我国野生动物研究与保护中的应用与前景

The importance of biodiversity and dominance for multiple ecosystem functions in a human-modified tropical landscape

DOI:10.1002/ecy.1499

URL

PMID:27859119

[本文引用: 1]

Many studies suggest that biodiversity may be particularly important for ecosystem multifunctionality, because different species with different traits can contribute to different functions. Support, however, comes mostly from experimental studies conducted at small spatial scales in low-diversity systems. Here, we test whether different species contribute to different ecosystem functions that are important for carbon cycling in a high-diversity human-modified tropical forest landscape in Southern Mexico. We quantified aboveground standing biomass, primary productivity, litter production, and wood decomposition at the landscape level, and evaluated the extent to which tree species contribute to these ecosystem functions. We used simulations to tease apart the effects of species richness, species dominance and species functional traits on ecosystem functions. We found that dominance was more important than species traits in determining a species' contribution to ecosystem functions. As a consequence of the high dominance in human-modified landscapes, the same small subset of species mattered across different functions. In human-modified landscapes in the tropics, biodiversity may play a limited role for ecosystem multifunctionality due to the potentially large effect of species dominance on biogeochemical functions. However, given the spatial and temporal turnover in species dominance, biodiversity may be critically important for the maintenance and resilience of ecosystem functions.

Volunteer-run cameras as distributed sensors for macrosystem mammal research

Recommended guiding principles for reporting on camera trapping research

Biodiversity hotspots and major tropical wilderness areas: Approaches to setting conservation priorities

DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.012003516.x URL [本文引用: 1]

The role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity and sustaining local livelihoods

Automatically identifying, counting, and describing wild animals in camera-trap images with deep learning

Camera Traps in Animal Ecology: Methods and Analyses. Springer, New York

Earth observation as a tool for tracking progress towards the Aichi Biodiversity Targets

Towards the global monitoring of biodiversity change

DOI:10.1016/j.tree.2005.10.015

URL

PMID:16701487

[本文引用: 2]

Governments have set the ambitious target of reducing biodiversity loss by the year 2010. The scientific community now faces the challenge of assessing the progress made towards this target and beyond. Here, we review current monitoring efforts and propose a global biodiversity monitoring network to complement and enhance these efforts. The network would develop a global sampling programme for indicator taxa (we suggest birds and vascular plants) and would integrate regional sampling programmes for taxa that are locally relevant to the monitoring of biodiversity change. The network would also promote the development of comparable maps of global land cover at regular time intervals. The extent and condition of specific habitat types, such as wetlands and coral reefs, would be monitored based on regional programmes. The data would then be integrated with other environmental and socioeconomic indicators to design responses to reduce biodiversity loss.

Global biodiversity monitoring: From data sources to essential biodiversity variables

Surveys using camera traps: Are we looking to a brighter future?

Assessing the suitability of diversity metrics to detect biodiversity change

Environmental science: Agree on biodiversity metrics to track from space

DOI:10.1038/523403a URL PMID:26201582 [本文引用: 1]

Scaling-up camera traps: Monitoring the planet’s biodiversity with networks of remote sensors

The value of museum collections for research and society

DOI:10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0066:TVOMCF]2.0.CO;2 URL [本文引用: 1]

Artificial intelligence’s role in global camera trap data management and analytics via Wildlife Insights

Future threats to biodiversity and pathways to their prevention

DOI:10.1038/nature22900

URL

PMID:28569796

[本文引用: 1]

Tens of thousands of species are threatened with extinction as a result of human activities. Here we explore how the extinction risks of terrestrial mammals and birds might change in the next 50 years. Future population growth and economic development are forecasted to impose unprecedented levels of extinction risk on many more species worldwide, especially the large mammals of tropical Africa, Asia and South America. Yet these threats are not inevitable. Proactive international efforts to increase crop yields, minimize land clearing and habitat fragmentation, and protect natural lands could increase food security in developing nations and preserve much of Earth's remaining biodiversity.

Projecting global biodiversity indicators under future development scenarios

Amur tigers and leopards returning to China: Direct evidence and a landscape conservation plan

The roles and contributions of Biodiversity Observation Networks (BONs) in better tracking progress to 2020 biodiversity targets: A European case study

Application of camera trapping to species inventory and assessment of wild animals across China’s protected areas

红外相机技术在我国自然保护地野生动物清查与评估中的应用

Overview of the Mammal Diversity Observation Network of Sino BON

中国兽类多样性监测网的建设规划与进展

An introduction to CameraData: An online dataset of wildlife camera

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1003.2014.14042 URL [本文引用: 1]

野生动物多样性监测图像数据管理系统CameraData介绍

Promoting diversity inventory and monitoring of birds through the camera-trapping network in China: Status, challenges and future outlook

DOI:10.17520/biods.2017057

URL

[本文引用: 1]

During the past two decades, camera-trapping has been widely used in biodiversity monitoring and wildlife research across China. Most of the existing camera-trapping projects focus on mammals, and birds are frequently considered in by-catch records. We analyzed 230 wildlife camera-trapping research projects in China since 1992, on the basis of an exhaustive review of Chinese and English literature, including published articles, conference reports, public news, and additional unpublished datasets. Results showed that at least 393 wild bird species, belonging to 17 orders and 56 families and accounting for 28.67% of the total number of bird species in China, have been documented using camera-trapping since 1992. The order with the most recorded species was Passeriformes (268). On the family level, Turdidae had the highest number of recorded species (58), followed by Timaliidae (50) and Phasianidae (42). There were 23 families that each only had one recorded species. Ground- and understory-dwelling forest birds accounted for the majority of all birds recorded, in terms of either species richness or camera detections. Published bird records were characterized by regional imbalances. Sichuan and Yunnan provinces were the most surveyed provinces, with 16 and 14 sites, respectively. The highest species richness was recorded in Sichuan (160), followed by Yunnan (91) and Zhejiang (66). A total of 104 new regionally recorded species were reported. Given the fact that there is still an abundance of camera-trapping data that has not been published, we speculated that the actual recorded bird species should be higher. These results indicated that camera-trapping can produce considerable bird distribution data of high accuracy, high quality and large amounts, which may provide a significant contribution to biodiversity monitoring and regional inventories of birds in China. Terrestrial birds, including Galliformes, Turdidae and Timaliidae, should be included as one of the target groups in current and future monitoring networks using standardized camera-trapping techniques, and such networks could also complement data and support the inventory and diversity monitoring of other taxa.

基于红外相机网络促进我国鸟类多样性监测: 现状、问题与前景